The

Glorious Revolution, also called the Revolution of 1688, was the overthrow

of King James II of England (James VII of Scotland and James II of Ireland) by

a union of English Parliamentarians with the Dutch stadtholder William III of

Orange-Nassau (William of Orange). William's successful invasion of England

with a Dutch fleet and army led to his ascending of the English throne as

William III of England jointly with his wife Mary II of England, in conjunction

with the documentation of the Bill of Rights 1689.

|

| James II |

|

| The Bill of Rights presented to William and Mary |

King

James's policies of religious tolerance after 1685 met with increasing

opposition by members of leading political circles, who were troubled by the

king's Catholicism and his close ties with France. The crisis facing the king

came to a head in 1688, with the birth of the King's son, James Francis Edward

Stuart, on 10 June (Julian calendar). This changed the existing line of

succession by displacing the heir presumptive, his daughter Mary, a Protestant

and the wife of William of Orange, with young James as heir apparent. The

establishment of a Roman Catholic dynasty in the kingdoms now seemed likely.

Some of the most influential leaders of the Tories united with members of the

opposition Whigs and set out to resolve the crisis by inviting William of

Orange to England, which the stadtholder, who feared an Anglo-French alliance,

had indicated as a condition for a military intervention.

After

consolidating political and financial support, William crossed the North Sea and

English Channel with a large invasion fleet in November 1688, landing at

Torbay. After only two minor clashes between the two opposing armies in

England, and anti-Catholic riots in several towns, James's regime collapsed,

largely because of a lack of resolve shown by the king. However, this was

followed by the protracted Williamite War in Ireland and Dundee's rising in

Scotland. In England's distant American colonies, the revolution led to the

collapse of the Dominion of New England and the overthrow of the Province of

Maryland's government. Following a defeat of his forces at the Battle of

Reading on 9 December, James and his wife fled England; James, however,

returned to London for a two-week period that culminated in his final departure

for France on 23 December. By threatening to withdraw his troops, William in

February 1689 convinced a newly chosen Convention Parliament to make him and

his wife joint monarchs.

William III (4 November

1650 – 8 March 1702) was sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Gelderland,

and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from 1672, and King of England, Ireland, and Scotland from

1689 until his death. It is a coincidence that his regnal number (III) was the same for both Orange

and England. As King of Scotland, he is known as William II. He is

informally and affectionately known by sections of the population in Northern Ireland and Scotland as "King Billy".

William inherited the principality of Orange from his father, William II, who died a week before William's birth. His mother Mary, Princess Royal, was the daughter of King Charles I of England. In 1677, he married his mother's fifteen-year-old niece and his first cousin, Mary, the daughter of his maternal uncle James, Duke of York.

A Protestant, William participated in several wars against the powerful Catholic king of France, Louis XIV, in coalition with Protestant and Catholic powers in Europe. Many Protestants heralded him as a champion of their faith. In 1685, his Catholic father-in-law, James, became king of England, Ireland and Scotland. James's reign was unpopular with the Protestant majority in Britain. William, supported by a group of influential British political and religious leaders, invaded England in what became known as the "Glorious Revolution". On 5 November 1688, he landed at the southern English port of Brixham. James was deposed and William and Mary became joint sovereigns in his place. They reigned together until her death on 28 December 1694, after which William ruled as sole monarch.

|

| William III by Thomas Murray, c. 1690 |

William inherited the principality of Orange from his father, William II, who died a week before William's birth. His mother Mary, Princess Royal, was the daughter of King Charles I of England. In 1677, he married his mother's fifteen-year-old niece and his first cousin, Mary, the daughter of his maternal uncle James, Duke of York.

A Protestant, William participated in several wars against the powerful Catholic king of France, Louis XIV, in coalition with Protestant and Catholic powers in Europe. Many Protestants heralded him as a champion of their faith. In 1685, his Catholic father-in-law, James, became king of England, Ireland and Scotland. James's reign was unpopular with the Protestant majority in Britain. William, supported by a group of influential British political and religious leaders, invaded England in what became known as the "Glorious Revolution". On 5 November 1688, he landed at the southern English port of Brixham. James was deposed and William and Mary became joint sovereigns in his place. They reigned together until her death on 28 December 1694, after which William ruled as sole monarch.

|

| William boarding the Brill |

William's

reputation as a strong Protestant enabled him to take the British crowns when

many were fearful of a revival of Catholicism under James. William's final

victory at the Battle of the Boyne in

1690 is still commemorated by

the Orange Order. His reign in Britain marked the beginning

of the transition from the personal rule of the Stuarts to the more Parliament-centred rule of the House of Hanover.

After Mary died in 1694, William ruled

alone until his death in 1702. William and Mary were childless and were

ultimately succeeded by Mary's younger sister, Anne.

Anne (6 February 1665 – 1 August 1714) became Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland on 8 March 1702. On 1 May 1707, under the Acts of Union, two of her realms, the kingdoms of England and Scotland, united as a single sovereign state known as Great Britain. She continued to reign as Queen of Great Britain and Ireland until her death.

Anne was born in the reign of her uncle Charles II, who had no legitimate children. Her father, James, was first in line to the throne. His suspected Roman Catholicism was unpopular in England, and on Charles's instructions Anne was raised as an Anglican. Three years after he succeeded Charles, James was deposed in the "Glorious Revolution" of 1688. Anne's Dutch Protestant brother-in-law and cousin William III became joint monarch with his wife, Anne's elder sister Mary II. Although the sisters had been close, disagreements over Anne's finances, status and choice of acquaintances arose shortly after Mary's accession and they became estranged. William and Mary had no children. After Mary's death in 1694, William continued as sole monarch until he was succeeded by Anne upon his death in 1702.

Anne (6 February 1665 – 1 August 1714) became Queen of England, Scotland and Ireland on 8 March 1702. On 1 May 1707, under the Acts of Union, two of her realms, the kingdoms of England and Scotland, united as a single sovereign state known as Great Britain. She continued to reign as Queen of Great Britain and Ireland until her death.

Anne was born in the reign of her uncle Charles II, who had no legitimate children. Her father, James, was first in line to the throne. His suspected Roman Catholicism was unpopular in England, and on Charles's instructions Anne was raised as an Anglican. Three years after he succeeded Charles, James was deposed in the "Glorious Revolution" of 1688. Anne's Dutch Protestant brother-in-law and cousin William III became joint monarch with his wife, Anne's elder sister Mary II. Although the sisters had been close, disagreements over Anne's finances, status and choice of acquaintances arose shortly after Mary's accession and they became estranged. William and Mary had no children. After Mary's death in 1694, William continued as sole monarch until he was succeeded by Anne upon his death in 1702.

|

| Queen Anne, circa 1702 |

Anne was

plagued by ill health throughout her life. From her thirties onwards, she grew

increasingly lame and obese. Despite seventeen pregnancies by her husband, Prince George of Denmark, she died without any surviving

children and was the last monarch of the House of Stuart.

Under the terms of the Act of Settlement 1701, she was succeeded by her second cousin George I of the House of Hanover,

who was a descendant of the Stuarts through his maternal grandmother, Elizabeth, a daughter of James VI and I.

The

Revolution permanently ended any chance of Catholicism becoming re-established

in England. For British Catholics its effects were disastrous both socially and

politically: Catholics were denied the right to vote and sit in the Westminster

Parliament for over a century; they were also denied commissions in the army,

and the monarch was forbidden to be Catholic or to marry a Catholic, this

latter prohibition remaining in force until the UK's Succession to the Crown

Act 2013 removed it in 2015. The Revolution led to limited toleration for

Nonconformist Protestants, although it would be some time before they had full

political rights. It has been argued, mainly by Whig historians, that James's

overthrow began modern English parliamentary democracy: the Bill of Rights 1689

has become one of the most important documents in the political history of Britain

and never since has the monarch held absolute power.

Internationally,

the Revolution was related to the War of the Grand Alliance on mainland Europe.

It has been seen as the last successful invasion of England. It ended all

attempts by England in the Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th century to subdue the

Dutch Republic by military force. However, the resulting economic integration

and military co-operation between the English and Dutch navies shifted the

dominance in world trade from the Dutch Republic to England and later to Great

Britain.

The

expression "Glorious Revolution" was first used by John Hampden in

late 1689, and is an expression that is still used by the British Parliament.

The Glorious Revolution is also occasionally termed the Bloodless Revolution,

albeit inaccurately. The English Civil War (also known as the Great Rebellion)

was still within living memory for most of the major English participants in

the events of 1688, and for them, in comparison to that war (or even the

Monmouth Rebellion of 1685) the deaths in the conflict of 1688 were mercifully

few.

2. The Middle-Class Cultural Revolution during XVI-XVII-th century

A. Tudor society (XVI-th century) - the House of Tudor was a royal house

of Welsh and English origin, descended in the male line from the Tudors of

Penmynydd. Tudor monarchs ruled the Kingdom of England and its realms,

including their ancestral Wales and the Lordship of Ireland (later the Kingdom

of Ireland) from 1485 until 1603, with 6 monarchs in that period. The first

monarch, Henry VII, descended through his mother from a legitimised branch of

the English royal House of Lancaster. The Tudor family rose to power in the

wake of the Wars of the Roses, which left the House of Lancaster, to which the

Tudors were aligned, extinct.

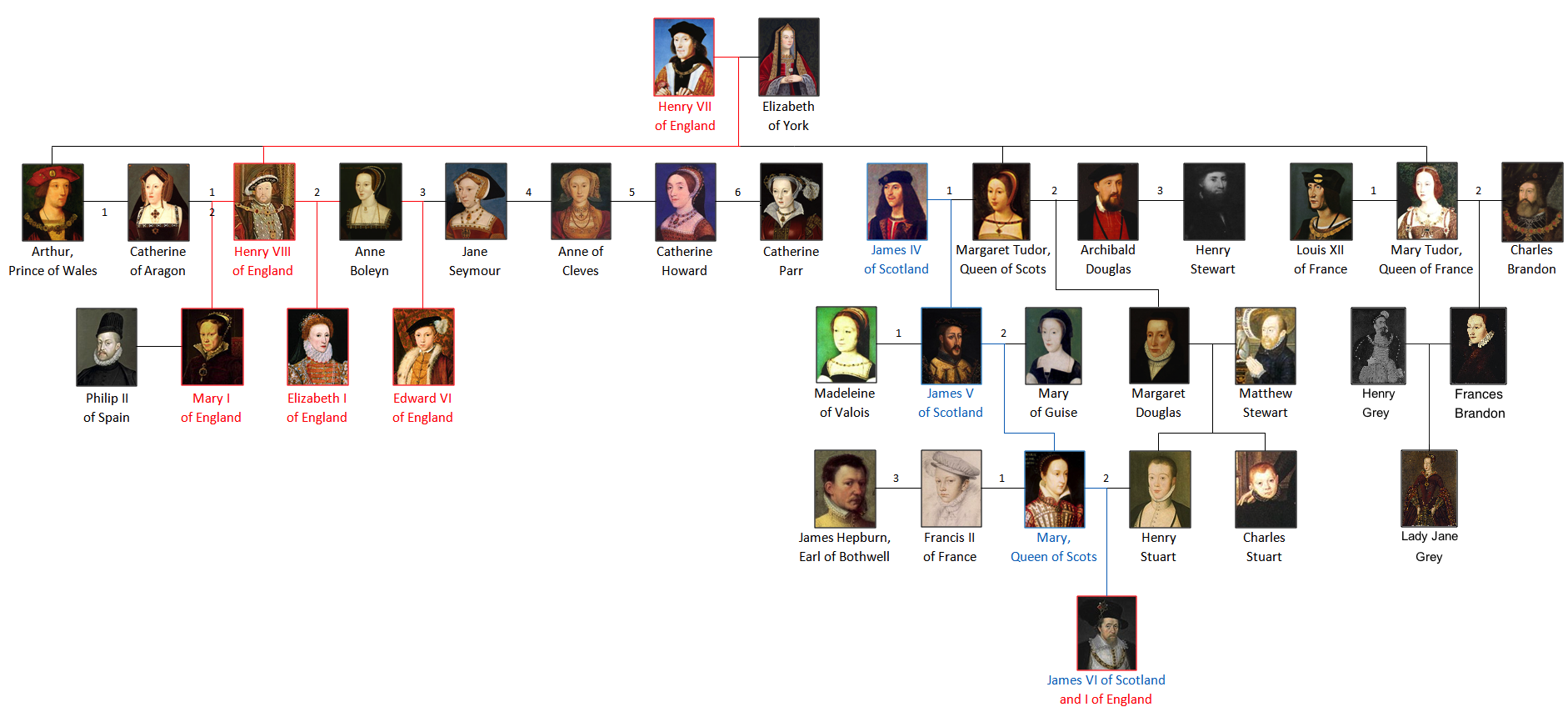

Family

tree of the principal members of the house of Tudor

Henry Tudor was able to establish himself as a candidate not only for traditional Lancastrian supporters, but also for the discontented supporters of their rival House of York, and he rose to capture the throne in battle, becoming Henry VII. His victory was reinforced by his marriage to Elizabeth of York, symbolically uniting the former warring factions under a new dynasty. The Tudors extended their power beyond modern England, achieving the full union of England and the Principality of Wales in 1542 (Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542), and successfully asserting English authority over the Kingdom of Ireland. They also maintained the nominal English claim to the Kingdom of France; although none of them made substance of it, Henry VIII fought wars with France trying to reclaim that title. After him, his daughter Mary I lost control of all territory in France permanently with the fall of Calais in 1558.

In

total, five Tudor monarchs ruled their domains for just over a century. Henry VIII

of England was the only male-line male heir of Henry VII to live to the age of

maturity. Issues around the royal succession (including marriage and the

succession rights of women) became major political themes during the Tudor era.

The House of Stuart came to power in 1603 when the Tudor line failed, as

Elizabeth I died without a legitimate heir.

In

general terms, the Tudor dynasty period was seen as relatively stable compared

to the previous years of almost constant warfare. However, the Reformation caused

internal and external social conflict, with a considerable impact on social

structure and personality.

Before

they were broken up and sold by Henry VIII, monasteries had been one of the

important parts of social welfare, giving alms and looking after the destitute,

and their disappearance meant that the state would have to adopt this role,

which culminated in the Poor law of 1601. The monasteries were decrepit—they no

longer were the major educational or economic establishments in the country;

after they had gone, many new grammar schools were founded and these, along

with the earlier introduction of the printing press, helped to improve

literacy.

Food and agriculture - the

agricultural reforms which had begun in the 13th century accelerated in the 16th

century, with enclosure altering the open field system and denying many of the

poor access to land. Large areas of land which had once been common, and whose

usage had been shared between many people, were now being enclosed by the

wealthy mainly for extremely profitable sheep farming.

England's

food supply was plentiful throughout most of the era; there were no famines.

Bad harvests caused distress, but they were usually localized. The most

widespread came in 1555–57 and 1596–98. In the towns the price of staples was

fixed by law; in hard times the size of the loaf of bread sold by the baker was

smaller.

The

poor consumed a diet largely of bread, cheese, milk, and beer, with small

portions of meat, fish and vegetables, and occasionally some fruit. Potatoes

were just arriving at the end of the period, and became increasingly important.

The typical poor farmer sold his best products on the market, keeping the cheap

food for the family. Stale bread could be used to make bread puddings, and

bread crumbs served to thicken soups, stews, and sauces. At a somewhat higher

social level families ate an enormous variety of meats, especially beef,

mutton, veal, lamb, and pork, as well as chickens, and ducks. The holiday goose

was a special treat. Many rural folk and some townspeople tended a small garden

which produced vegetables such as asparagus, cucumbers, spinach, lettuce,

beans, cabbage, carrots, leeks, and peas, as well as medicinal and flavoring

herbs. Some raised their own apricots, grapes, berries, apples, pears, plums,

currants, and cherries. Families without a garden could trade with their

neighbours to obtain vegetables and fruits at low cost.

The

people discovered new foods (such as the potato and tomato imported from the

Americas), and developed new tastes during the era. The more prosperous enjoyed

a wide variety of food and drink, including exotic new drinks such as tea,

coffee, and chocolate. French and Italian chefs appeared in the country houses

and palaces bringing new standards of food preparation and taste. For example,

the English developed a taste for acidic foods—such as oranges for the upper

class—and started to use vinegar heavily. The gentry paid increasing attention

to their gardens, with new fruits, vegetables and herbs; pasta, pastries, and

dried mustard balls first appeared on the table. The apricot was a special

treat at fancy banquets. Roast beef remained a staple for those who could

afford it. The rest ate a great deal of bread and fish. Every class had a taste

for beer and rum.

At

the rich end of the scale the manor houses and palaces were awash with large,

elaborately prepared meals, usually for many people and often accompanied by

entertainment. Often they celebrated religious festivals, weddings, alliances

and the whims of her majesty.

B. Stuard period (XVII-th century) -

the Stuart period of British history usually refers to the period between 1603

and 1714 and sometimes from 1371 in Scotland. This coincides with the rule of

the House of Stuart, whose first monarch of Scotland was Robert II but who

during the reign of James VI of Scotland also inherited the throne of England.

The period ended with the death of Queen Anne and the accession of George I

from the House of Hanover. The Stuart period was plagued by internal and

religious strife, and a large-scale civil war.

England

was wracked by civil war over religious issues. Prosperity generally continued

in both rural areas and the growing towns, as well as the great metropolis of

London.

The

English civil war was far from just a conflict between two religious faiths,

and indeed it had much more to do with divisions within the one Protestant

religion. The austere, fundamentalist Puritanism on the one side was opposed to

what it saw as the crypto-Catholic decadence of the Anglican church on the

other. Divisions also formed along the lines of the common people and the

gentry, and between the country and city dwellers. It was a conflict that was

bound to disturb all parts of society, and a frequent slogan of the time was

"the world turned upside down".

In

1660 the Restoration was a quick transition back to the high church Stuarts.

Public opinion reacted against the puritanism of the Puritans, such as the

banning of traditional pastimes of gambling, cockfights, the theatre and even

Christmas celebrations. The arrival of Charles II—The Merry Monarch—brought a

relief from the warlike and then strict society that people had lived in for

several years. The theatre returned, along with expensive fashions such as the

periwig and even more expensive commodities from overseas. The British Empire

grew rapidly after 1600, and along with wealth returning to the country,

expensive luxury items were also appearing. Sugar and coffee from the East

Indies, tea from India and slaves (brought from Africa to the sugar colonies,

along with some enslaved servants in England itself) formed the backbone of

imperial trade.

One

in nine Englishmen lived in London near the end of the Stuart period. However plagues were even more deadly in a crowded city—the only remedy was to

move to isolated rural areas, as Isaac Newton of Cambridge University did in

1664–66 as the Great Plague of London killed as many as 100,000 Londoners. The

fast-growing metropolis was the centre of politics, high society and business.

As a major port and hub of trade, goods from all over were for sale. Coffee

houses were becoming the centres of business and social life, and it has also

been suggested that tea might have played its own part in making Britain

powerful, as the antiseptic qualities of tea allowed people to live closer

together, protecting them from germs, and making the Industrial Revolution

possible. These products can be considered as beginning the consumer society

which, while it promoted trade and brought development and riches to society.

|

| London in XVI-th century |

Newspapers,

were new and soon became important tools of social discourse and the diarists

of the time such as Samuel Pepys and John Evelyn are some of the best sources

we have of everyday life in Restoration England.

Coffee houses grew numerous and were places for middle class men to meet, read the papers, look over new books and gossip and share opinions. Thomas Garway operated a coffee house in London from 1657 to 1722. He sold tea, tobacco, snuff, and sandwiches. Businessmen met there informally; the first furs from the Hudson's Bay Company were auctioned there.

Coffee houses grew numerous and were places for middle class men to meet, read the papers, look over new books and gossip and share opinions. Thomas Garway operated a coffee house in London from 1657 to 1722. He sold tea, tobacco, snuff, and sandwiches. Businessmen met there informally; the first furs from the Hudson's Bay Company were auctioned there.

The

diet of the poor in the 1660–1750 era was largely bread, cheese, milk, and

beer, with small quantities of meat and vegetables. The more prosperous enjoyed

a wide variety of food and drink, including tea, coffee, and chocolate.

3. The American War of Independence (1775-1783)

A. General information - the American

Revolutionary War (1775–1783), also known as the American War of Independence and the Revolutionary War in the United States, was the armed conflict

between Great

Britain and thirteen

of its North American colonies, which had declared themselves the independent United

States of America. Early

fighting took place primarily on the North American continent. France, eager

for revenge after its defeat in the Seven

Years' War, signed an alliance with the

new nation in 1778 that proved decisive in the ultimate victory. The conflict gradually expanded into a world

war with Britain combating France, Spain, and the

Netherlands. Fighting also broke out in India between the British East

India Company and the French allied Kingdom

of Mysore.

A. General information - the American

Revolutionary War (1775–1783), also known as the American War of Independence and the Revolutionary War in the United States, was the armed conflict

between Great

Britain and thirteen

of its North American colonies, which had declared themselves the independent United

States of America. Early

fighting took place primarily on the North American continent. France, eager

for revenge after its defeat in the Seven

Years' War, signed an alliance with the

new nation in 1778 that proved decisive in the ultimate victory. The conflict gradually expanded into a world

war with Britain combating France, Spain, and the

Netherlands. Fighting also broke out in India between the British East

India Company and the French allied Kingdom

of Mysore.

The American

Revolutionary War had its origins in the resistance of many Americans to

taxes, which

they claimed were unconstitutional, imposed by the British parliament. Patriot protests

escalated into boycotts, and on December 16, 1773, the destruction of a

shipment of tea at the Boston Tea Party. The British government

retaliated by closing the port of Boston and taking away self-government. The

Patriots responded by setting

up a shadow government that took control of the province outside of

Boston. Twelve other colonies supported Massachusetts, formed a Continental Congress to

coordinate their resistance, and set up committees and conventions that

effectively seized power. In April 1775 the battles of Lexington and Concord, in Middlesex County, near Boston,

began open armed conflict between the Kingdom of Great Britain and thirteen of

its colonies. The Continental Congress appointed General George Washington to take

charge of militia units besieging British forces in Boston, forcing them to

evacuate the city in March 1776. Congress supervised the war, giving Washington

command of the new Continental Army; he also coordinated state militia units.

On July 2,

1776, the Continental

Congress formally

voted for independence, and issued its Declaration on July 4. Meanwhile, the British were mustering forces to

suppress the revolt. Sir William Howe outmaneuvered

and defeated Washington, capturing New York City and New Jersey. Washington was

able to capture a Hessian detachment at Trenton and

drive the British out of most of New Jersey. In 1777 Howe's army launched a

campaign against the national capital at Philadelphia, failing to aid Burgoyne's separate

invasion force from Canada. Burgoyne's army was trapped and surrendered after

the Battles of Saratoga in

October 1777.

This American

victory encouraged France to enter the war in 1778, followed by

its ally Spain in 1779, although not directly allied with America. Many people

in Europe, especially in Spain and the Netherlands, believe that the new nation,

technically British in American soil, shared the same imperialistic trait as

Britain. So instead, Spain allied with France under Pacte

de Famille.

In 1778,

having failed in the northern states, the British shifted strategy toward the

south, bringing Georgia and South Carolina under control in 1779 and 1780.

However, the resulting surge of Loyalist support was far weaker than expected.

In 1781, British forces moved through Virginia and settled at Yorktown, but

their escape was blocked by a French naval victory in

September. Led by Count

Rochambeau and Washington, a combined The Franco-American army launched a siege

at Yorktown and captured more than 8,000 British troops in October.

The defeat at

Yorktown finally turned the British Parliament against the war, and in early

1782 they voted to end offensive operations in North America. The war against

France and Spain continued, with the British defeating the long siege of Gibraltar, and

inflicting several defeats on the French in 1782.

In 1783, the Treaty of Paris ended

the war and recognized the sovereignty of the United States over the territory

bounded roughly by what is now Canada to the north, Florida to the

south, and the Mississippi River to the

west. France gained its revenge and little else except a heavy national debt,

while Spain acquired Great Britain's Florida colonies.

B. Causes

Taxes - The close of

the Seven Years' War in 1763

(called the French and Indian War in

America) saw Great Britain triumphant in driving the French from North America.

Though triumphant, Britain had been forced to borrow heavily to win the war, in

particular in using the American colonies as a base for invading and seizing

French territories. In the year between 1763-4, the British revenue service in

America cost four times more to administer than it collected in duties, and London, therefore, decided that it was time to end

the policy of Salutary Neglect, and enforce

a more vigorous approach to collecting legal revenues from the thirteen

colonies. Since the earliest times, Americans had experienced an extremely

relaxed approach towards smuggling. Nowhere in the British Empire were taxes as

low as in the thirteen colonies - India and Britain itself was subjected to

much higher levels of exploitation. For example, the 1733 Molasses Act,

introduced to protect the plantations from their more productive French

counterparts, imposed a tax of sixpence per gallon on imports of molasses from

non-British West Indian colonies. But it was so heavily violated that it

produced only a trickle of revenue; twenty years later, only 384 hogsheads of

molasses officially entered Boston, a town housing 63 rum distilleries that

together required an annual 40,000 hogsheads of molasses to maintain normal

production.

Parliament

passed the Stamp Act (an act of the British Parliament in 1756 that

exacted revenue from the American colonies by imposing a stamp duty on

newspapers and legal and commercial documents. Colonial opposition led to the

act's repeal in 1766 and helped encourage the revolutionary movement against

the British Crown.) in March 1765, which imposed direct taxes on the colonies

for the first time starting November 1. This was met with strong condemnation

among American spokesmen, who argued that their "Rights as

Englishmen" meant that taxes could not be imposed on them because

they lacked representation in Parliament. At the same time the colonists rejected the solution of being provided with

the representation, claiming that "their local circumstances" made it

impossible.

Civil resistance

prevented the Act from being enforced, and organized boycotts of British goods

were instituted. This resistance was by and large unexpected and "produced

a violent and very natural irritation."

A change of

government in Britain led to the repeal of the Stamp Act as inexpedient, but

also the passage of the Declaratory

Act, which stated, "the said colonies and plantations in America have

been, are, and of right ought to be, subordinate unto, and dependent upon the

imperial crown and parliament of Great Britain.”

In their

declarations Americans had deemed internal taxes like the Stamp Act as

unlawful, but not external taxes like custom duties. In 1767 Parliament passed

the Townshend Act in order to demonstrate its supremacy. It

imposed duties on various British goods exported to the colonies. The Americans

quickly denounced this as illegal as well, since the intent of the act was to

raise revenue and not regulate trade.

In 1768

violence broke out in Boston over attempts to suppress smuggling and 4000

British troops were sent to occupy the city. Parliament threatened to try

Massachusetts residents for treason in

England. Far from being intimidated, the colonists formed new associations to

boycott British goods, albeit with less effectiveness than previously since the

Townshend imports were so widely used. In March 1770 five colonists in Boston

were killed in the Boston

Massacre, sparking outrage. That

same year Parliament agreed to repeal all taxes except the one on tea.

In 1773, in an

effort to rescue the East

India Company from financial difficulties, the government

attempted to increase the company's tea sales by permotting direct export to

the colonies (reducing the price of its tea) while retaining the tax and

appointing certain merchants in America to receive and sell it. The landing of

this tea was resisted in all the colonies and, when the royal governor of

Massachusetts refused to send back the tea ships in Boston, Patriots destroyed

the tea chests.

Crisis

Nobody was punished for the "Boston Tea Party" and in 1774 Parliament ordered Boston Harbor closed until the destroyed tea was paid for. It then passed the Massachusetts Government Act to punish the rebellious colony. The upper house of the Massachusetts legislature would be appointed by the Crown, as was already the case in other colonies such as New York and Virginia. The royal governor was able to appoint and remove at will all judges, sheriffs, and other executive officials, and restrict town meetings. Jurors would be selected by the sheriffs and British soldiers would be tried outside the colony for alleged offenses. These were collectively dubbed the "Intolerable Acts" by the Patriots.

Although these actions were not unprecedented (the Massachusetts charter had already been replaced once before in 1691), the people of the colony were outraged. Town meetings resulted in the Suffolk Resolves, a declaration not to cooperate with the royal authorities. In October 1774 an illegal "provincial congress" was established which took over the governance of Massachusetts outside of British-occupied Boston and began training militia for hostilities.

This iconic 1846 lithograph by Nathaniel

Currier was entitled "The Destruction of Tea at

Boston Harbor"; the phrase "Boston Tea Party" had not yet become

standard. Contrary to Currier's depiction, few of the men dumping the tea were

actually disguised as Indians.

Meanwhile, in

September 1774 representatives of the other colonies convened the First Continental Congress in order

to respond to the crisis. The Congress rejected a "Plan of Union" to

establish an American parliament that could approve or disapprove of the acts

of the British parliament. Instead, they endorsed the Suffolk Resolves and

demanded the repeal of all Parliamentary acts passed since 1763, not merely the

tax on tea and the "Intolerable Acts". They stated that Parliament

had no authority over internal matters in America, but that they would

"cheerfully consent" to trade regulations, including customs duties

for the benefit of the empire. They also

required Britain to acknowledge that unilaterally stationing troops in the

colonies in a time of peace was "against the law". Although the

Congress lacked any legal authority, it ordered the creation of Patriot

committees who would enforce a boycott of British goods starting on December 1,

1774.

This time,

however, the British would not yield. Edmund

Burke introduced a motion to repeal all the Acts of Parliament the

Americans objected to and waive any rights of Britain to tax for revenue, but

it was defeated 210–105. Parliament voted to restrict all colonial trade to

Britain, prevent them from using the Newfoundland fisheries, and to

increase the size of the army and navy by 6,000. In February 1775 Prime

Minister Lord North proposed not to impose taxes if the colonies

themselves made "fixed contributions". This would safeguard the

taxing rights of the colonies from future infringement while enabling them to

contribute to maintenance of the empire. This proposal was nevertheless

rejected by the Congress in July as an "insidious maneuver", by which

time hostilities had broken out.

Internal

British politics - during this time the British did

not present a united front toward the American Patriots. The Parliament of Great

Britain at this time was informally divided between conservative (Tory) and liberal

(Whig) factions. The Whigs generally favored lenient

treatment of the colonists short of independence while the Tories staunchly

upheld the rights of Parliament. The Whigs felt that the Tory policies were

pushing Americans to rebel, while the Tories thought Whig leniency (such as repealing

the Stamp Act) was doing the same. Many Whigs freely associated themselves with

the American Patriot cause, which Tories thought were encouraging the Americans

in their resistance. The result was that, although Lord

North's Tory government usually had a Parliamentary majority, a large Whig

minority opposed it and constantly criticized its policies. Meanwhile, Whig commanders in America such as Sir

William Howe and his brother Admiral Howe came under the

suspicion of Tories and Loyalists for not vigorously prosecuting the war

effort.

4. The French Revolution and England

The

French Revolution had a major impact on Europe and the New World. In the

short-term, France lost thousands of her countrymen in the form of émigrés, or

emigrants who wished to escape political tensions and save their lives. A

number of individuals settled in the neighboring countries (chiefly Great

Britain, Germany, Austria, and Prussia), however quite a few also went to the

United States. The displacement of these Frenchmen led to a spread of French

culture, policies regulating immigration, and a safe haven for Royalists and

other counterrevolutionaries to outlast the violence of the French Revolution.

The long-term impact on France was profound, shaping politics, society,

religion and ideas, and polarizing politics for more than a century. The closer

other countries were, the greater and deeper was the French impact, bringing

liberalism and the end of many feudal or traditional laws and practices.

However there was also a conservative counter-reaction that defeated Napoleon,

reinstalled the Bourbon kings, and in some ways reversed the new reforms

Britain

saw minority support, but the majority, and especially the elite, strongly

opposed the French Revolution. Britain led and funded the series of coalitions

that fought France from 1793 to 1815, and then restored the Bourbons. Edmund

Burke was the chief spokesman for the opposition.

In

Ireland, the effect was to transform what had been an attempt by Protestant

settlers to gain some autonomy into a mass movement led by the Society of

United Irishmen involving Catholics and Protestants. It stimulated the demand

for further reform throughout Ireland, especially in Ulster. The upshot was a

revolt in 1798, led by Wolfe Tone, that was crushed by Britain.

The

ardour for liberty

'How

much the greatest event that has happened in the history of the world, and how

much the best' - Charles James Fox, Opposition Whig leader 1789

News

of the opening events of the French Revolution was greeted with widespread

enthusiasm by British observers, although some, patronisingly, saw it as

evidence that France was abandoning absolutism for a liberal constitution based

on the British model. Enthusiasm was most potent among those championing

domestic political reform - Dissenters excluded from political office by the

Test and Corporation and Subscription Acts, members of the middling orders

denied the vote by antiquated constituency boundaries and a restricted

suffrage, and Parliamentary Whigs whose ambitions for office were blocked by

Pitt's firm hold on power. For these groups and their associated literary,

scientific and political circles, events in France signified a much deeper

change in government.

I

see the ardour for liberty catching and spreading...

Following

hard on the American Revolution (1776-83), the sweeping aside of the French

feudal order demonstrated the irresistible rise of freedom and enlightenment.

In November 1789, Richard Price's sermon commemorating the Glorious Revolution

of 1688 concluded by hailing events in France as the dawn of a new era. 'Behold

all ye friends of freedom... behold the light you have struck out, after

setting America free, reflected to France and there kindled into a blaze that

lays despotism in ashes and warms and illuminates Europe. I see the ardour for

liberty catching and spreading; ...the dominion of kings changed for the

dominion of laws, and the dominion of priests giving way to the dominion of

reason and conscience.'

The

development into maturity of classical liberalism took place before and after

the French Revolution in Britain, and was based on the following core concepts:

classical economics, free trade, laissez-faire government with minimal

intervention and taxation and a balanced budget. Classical liberals were

committed to individualism, liberty and equal rights. The primary intellectual

influences on 19th century liberal trends were those of Adam Smith and the

classical economists, and Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill.

The

revolution controversy - Price's sermon attracted the wrath

of Edmund Burke - a leading Whig increasingly uncomfortable with the reformist

flirtations of his Whig friends, convinced that reform was destroying the

French state, and fearful that revolution would spread to Britain. Burke's

response, his powerful, deeply conservative, Reflections on the Revolution in

France... (1791) prophesied the destruction of civilisation in France and the

outbreak of European war. The pamphlet sparked an intense debate on fundamental

questions in politics fought out in over three hundred pamphlets - including

Thomas Paine's, Rights of Man, Mary Wollstonecraft's Vindication of the Rights

of Man, and James Mackintosh's Vindiciae Gallicae - and spilling over into

novels, poetry, popular song, and caricature.

The

debate rapidly became an escalating battle of political rhetoric and

mobilisation.

The

controversy gave renewed energy to metropolitan and provincial reform

societies, such as the Society for Constitutional Information (SCI), and

fuelled the emergence of new associations, some organised by ordinary working

people who declined the patronage and control of the wealthy. Thomas Hardy's

London Corresponding Society (LCS), formed early in 1792, spent five evenings

discussing whether they 'as treadesman (sic) shopkeepers and mechanics', had

any right to seek parliamentary reform. The society went on to become hugely

influential and developed scores of divisions and local branches.

The

debate rapidly became an escalating battle of political rhetoric and

mobilisation. Those sympathetic to reform were tarred with France's worst

revolutionary excesses and responded by taking their message to the mass of the

people through political organisation and the circulation of cheap pamphlets

and broadsides. Their most potent weapon, Paine's Rights of Man reached several

hundred-thousand readers. In May 1792, the government reacted with a Royal

Proclamation against seditious writing. In the subsequent prosecution of Paine,

the Attorney General succinctly expressed the government's anxieties: 'all

industry was used to obtrude and force this upon that part of the public whose

minds cannot be supposed to be conversant with subjects of this sort....

Gentlemen, to whom are these positions addressed...to the ignorant, to the

credulous, to the desperate.' Paine escaped to France but others were less

fortunate.

Reaction

- Government fears of popular

insurrection escalated in November and December 1792 when the French promised

armed support for all subject peoples and rumours of a London insurrection

swept the capital. The establishment of the Association for the Protection of

Liberty and Property against Republicans and Levellers helped turn the tide by

encouraging provincial correspondents to communicate with the London base,

enjoining the denunciation and prosecution of local radicals, and circulating

loyalist tracts and pamphlets to the middling and artisan classes. Branches

also organised local demonstrations of loyalty, including over 300 ritualised

burnings of Tom Paine.

...reformers

attempted to organise a National Convention to express popular support for

reform.

Petitions

and popular pressure for reform produced increasing intransigence in the

government and exacerbated tensions amongst the Whigs (culminating in the

defection of Burke and the Portland Whigs to Pitt in June 1794). In turn,

reformers attempted to organise a National Convention to express popular

support for reform. Such conventionism has precursors in the 1770s, but its

popularisation alarmed the government and the notorious Judge Braxfield reacted

punitively to the leaders of the Scottish and British Conventions of 1793 by

sentencing them to transportation.

Nonetheless,

plans for an English Convention continued and in May 1794, the government

arrested leading members of the SCI and LCS on suspicion of treason. The

evidence was relatively scanty, but much depended on the interpretation of the

statute of Edward II that defined treason in terms of 'compassing or imagining

the death of the King'. In a series of dramatic trials in October and November

1794 the accused were acquitted. But they were hardly exonerated - William

Windham denounced them in Parliament as 'acquitted felons'.

The

Two Acts - following the trials, the LCS

focussed on mobilising popular unrest against the war, taxation, food

shortages, and recruitment, through mass public meetings in June and October

1795. Days after the October meeting, during the state opening of Parliament,

the king's coach was attacked (the king claiming to have been shot at) and when

it returned empty it was destroyed by protesters. The government rushed in the

'Two Acts' or 'Gagging Acts' to tighten the treason statute and to ban large

political meetings. A huge petitioning campaign followed, with loyalists

expressing support and reformers protesting against the restriction, but the

Bills were passed.

...the

popular movement was driven underground and into more conspiratorial

activity...

The

Two Acts encouraged an increasingly close alliance between the Foxite Whigs and

the reformers. By the end of 1797 Fox was denouncing Pitt's 'reign of terror',

and later seceded from Parliament in protest. Meanwhile, following further

prosecutions and harassment, the popular movement was driven underground and

into more conspiratorial activity - emerging in a series of splinter groups -

the United Englishmen, United Irishmen and United Scotsmen.

5. The Georgian era and the dawn of the Industrial Revolution (1714 - 1830)

A. The house of Hanover - the House of Hanover (or the Hanoverians) is a German royal dynasty which has ruled the Duchy of

Brunswick-Lüneburg (German: Braunschweig-Lüneburg), the Kingdom of Hanover, the Kingdom of Great

Britain, the Kingdom of Ireland and

the United Kingdom of

Great Britain and Ireland. It succeeded the House of

Stuart as monarchs of Great Britain and Ireland in 1714 and held that office until the

death of Queen Victoria in

1901.

B. Social change during the Georgian era - it was a time of immense social change in Britain, with the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution which began the process of intensifying class divisions, and the emergence of rival political parties like the Whigs and Tories.

George Louis became the first British

monarch of the House of Hanover as George I in 1714. The dynasty provided six British monarchs:

Of the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland:

George I (r.1714–27) (Georg Ludwig = George Louis)

George II (r.1727–60)

(Georg August = George Augustus)

George III (r.1760–1820)

George III (r.1760–1820)

George IV (r.1820–30)

William IV (r.1830–37)

Victoria (r.1837–1901)

B. Social change during the Georgian era - it was a time of immense social change in Britain, with the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution which began the process of intensifying class divisions, and the emergence of rival political parties like the Whigs and Tories.

In rural areas

the Agricultural Revolution saw huge

changes to the movement of people and the decline of small communities, the

growth of the cities and the beginnings of an integrated transportation system but,

nevertheless, as rural towns and villages declined and work became scarce there

was a huge increase in emigration to Canada, the North American colonies (which became the United States during

the period) and other parts of the British Empire.

Social reform under

politicians such as Robert

Peel and campaigners like William

Wilberforce, Thomas

Clarkson and members of the Clapham

Sect began to bring about radical change in areas such as the abolition of slavery, prison

reform and social justice. An

Evangelical revival was seen in the Church of England with men

such as George Whitefield, John

Wesley (later to found the Methodists), Charles

Wesley, Griffith Jones, Howell Harris, Daniel Rowland, William Cowper, John

Newton, Thomas Scott, and Charles Simeon. It also saw the rise of Non-conformists and various dissenting groups

such as the Reformed

Baptists with John Gill, Augustus Toplady, John Fawcett, and William Carey.

Philanthropists

and writers such as Hannah

More, Thomas Coram, Robert Raikes and Beilby Porteus, Bishop of London, began to

address the social ills of the day, and saw the founding of hospitals, Sunday schools and

orphanages.

Fine examples

of distinctive Georgian architecture are Edinburgh's New

Town, Georgian

Dublin, Grainger Town in Newcastle

Upon Tyne, and much of Bristol and Bath.

Middle class and stability - the middle class grew rapidly in the 18th century,

especially in the cities. At the top of the scale The legal profession

succeeded first, establishing specialist training and associations, and was

soon followed by the medical profession. The merchant class prospered with

imperial trade. Wahrman (1992) argues that the new urban elites included two

types: the gentlemanly capitalist, who participated in the national society,

and the independent bourgeois, who was oriented toward the local community. By

the 1790s a self-proclaimed middle class, with a particular sociocultural

self-perception, had emerged.

Thanks to increasing national wealth, upward mobility

into the middle class, urbanisation, and civic stability, Britain was

relatively calm and stable, certainly compared with the revolutions and wars

which were convulsing the American colonies, France and other nations at the

time. The politics of the French Revolution did not translate directly into

British society to spark an equally seismic revolution, nor did the loss of the

American Colonies dramatically weaken or disrupt Great Britain.

|

| View of Old London Bridge |

C. Empire - the Georgian

era was moreover a time of British expansion throughout the world. There was

continual warfare, including the Seven Years' War, known in America as the French

and Indian War (1756–63), the American Revolutionary War (1775–83),

the French Revolutionary Wars (1792–1802),

the Irish

Rebellion of 1798, and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–15). The British won all the wars except

for the American Revolution, where the combined weight of the United States,

France, Spain and the Netherlands overwhelmed Britain, which stood alone

without allies.

|

| Colonel Blair with his Family and an Indian Ayah 1786 |

The Age of Mercantilism (1600-1750) - was the basic policy imposed by Britain on its

colonies. Mercantilism

meant that the government and the merchants became partners with the goal of

increasing political power and private wealth, to the exclusion of other

empires. The government protected its merchants — and kept others out—by trade barriers, regulations, and subsidies to domestic

industries in order to maximise exports from and minimise imports to the realm.

The government had to fight smuggling, which became a favourite American

technique in the 18th century to circumvent the restrictions on trading with

the French, Spanish or Dutch. The goal of mercantilism was to run trade

surpluses, so that gold and silver would pour into London. The government took

its share through duties and taxes, with the remainder going to merchants in

Britain. The government spent much of its revenue on a large and powerful Royal

Navy, which not only protected the British colonies but threatened the colonies

of the other empires, and sometimes seized them. The colonies were captive

markets for British industry, and the goal was to enrich the mother country.

|

| An imaginary seaport with a transposed Villa Medici, painted by Claude Lorrain around 1637, at the height of mercantilism |

D. The Industrial Revolution (1770s-1820s)

Historians typically date the coming of the Industrial Revolution to Britain in the mid-18th century. Not only did existing cities grow but small market towns such as Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds became cities simply by weight of population.

Historians typically date the coming of the Industrial Revolution to Britain in the mid-18th century. Not only did existing cities grow but small market towns such as Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds became cities simply by weight of population.

In a period

loosely dated from the 1770s to the 1820s, Britain experienced an accelerated

process of economic change that transformed a largely agrarian economy into the

world's first industrial economy. This phenomenon is known as the "industrial

revolution", since the changes were all embracing and permanent throughout many

areas of Britain, especially in the developing cities.

Iron and Coal, 1855–60, by William Bell Scott illustrates the rise of coal and iron working in the Industrial Revolution and the heavy engineering projects

Great Britain

provided the legal and cultural foundations that enabled entrepreneurs to

pioneer the industrial revolution. Starting in

the later part of the 18th century, there began a transition in parts of Great

Britain's previously manual labour and draft-animal–based economy towards

machine-based manufacturing. It started with the mechanisation of the textile

industries, the development of iron-making techniques

and the increased use of refined coal. Trade

expansion was enabled by the introduction of canals, improved roads and railways. Factories

pulled thousands from low productivity work in agriculture to high productivity

urban jobs.

The introduction

of steam power fuelled

primarily by coal, wider utilisation of water wheels and

powered machinery (mainly in textile

manufacturing) underpinned the dramatic increases in production

capacity. The development of all-metal machine

tools in the first two decades of the 19th century facilitated the

manufacture of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries.

The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th

century, eventually affecting most of the world, a process that continues as industrialisation.

According

to Max Weber, the

foundations of this process of change can be traced back to the Puritan Ethic

of the Puritans of the 17th century. This produced

modern personalities atuned to innovation and committed to a work ethic,

inspiring landed and merchant elites alive to the benefits of modernization,

and a system of agriculture able to produce increasingly cheap food supplies.

To this must be added the influence of religious nonconformity, which increased

literacy and inculcated a "Protestant work ethic" amongst

skilled artisans.

A long run of

good harvests, starting in the first half of the 18th century, resulted in an

increase in disposable income and a consequent rising demand for manufactured

goods, particularly textiles. The invention of the flying shuttle by John

Kay enabled wider cloth to be woven faster, but also created a demand for

yarn that could not be fulfilled. Thus, the major technological advances

associated with the industrial revolution were concerned with spinning. James Hargreaves created

the Spinning Jenny, a device

that could perform the work of a number of spinning wheels. However, while this

invention could be operated by hand, the water frame, invented

by Richard

Arkwright, could be powered by a water

wheel. Indeed, Arkwright is credited with the widespread introduction of

the factory

system in Britain, and is the first example of the successful mill owner and

industrialist in British history. The water frame was, however, soon supplanted

by the spinning mule (a cross

between a water frame and a jenny) invented by Samuel Crompton. Mules were

later constructed in iron by Messrs. Horrocks of Stockport.

As they were

water powered, the first mills were constructed in rural locations by streams

or rivers. Workers villages were created around them, such as New

Lanark Mills in Scotland. These spinning mills resulted in the decline of

the domestic

system, in which spinning with old slow equipment was undertaken in rural

cottages.

The steam engine was

invented and became a power supply that soon surpassed waterfalls and

horsepower. The first practicable steam engine was invented by Thomas Newcomen, and was used

for pumping water out of mines. A much more powerful steam engine was invented

by James Watt; it had

a reciprocating

engine capable of powering machinery. The first steam-driven textile mills

began to appear in the last quarter of the 18th century, and this transformed

the industrial revolution into an urban phenomenon, greatly contributing to the

appearance and rapid growth of industrial towns.

|

| James Eckford Lauder: James Watt and the Steam Engine: the Dawn of the Nineteenth Century |

The progress

of the textile trade soon outstripped the original supplies of raw materials.

By the turn of the 19th century, imported American cotton had replaced wool in

the North

West of England, though wool remained the chief textile in Yorkshire. Textiles

have been identified as the catalyst in technological change in this period.

The application of steam power stimulated the demand for coal; the demand for

machinery and rails stimulated the iron industry; and the

demand for transportation to move raw material in and finished products out

stimulated the growth of the canal system, and (after 1830) the railway system.

Such an

unprecedented degree of economic growth was not sustained by domestic demand

alone. The application of technology and the factory system created such levels

of mass

production and cost efficiency that enabled British manufacturers to export

inexpensive cloth and other items worldwide.

Interior of Marshall's Temple Works

Walt

Rostow has posited the 1790s as the "take-off" period for the

industrial revolution. This means that a process previously responding to

domestic and other external stimuli began to feed upon itself, and became an

unstoppable and irreversible process of sustained industrial and technological

expansion.

In the late

18th century and early 19th century a series of technological advances led to

the Industrial

Revolution. Britain's position as the world's pre-eminent trader helped fund research

and experimentation. The nation also had some of the world's greatest reserves

of coal, the main

fuel of the new revolution.

It was also

fuelled by a rejection of mercantilism in favour of the predominance of Adam Smith's capitalism. The fight

against Mercantilism was led by a number of liberal thinkers,

such as Richard

Cobden, Joseph Hume, Francis Place and John

Roebuck.

Some have

stressed the importance of natural or financial resources that Britain received

from its many overseas colonies or that profits from the British slave trade between

Africa and the Caribbean helped fuel industrial investment. It has been pointed

out, however, that slave trade and the West Indian plantations

provided less than 5% of the British national income during the years of the

Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial

Revolution saw a rapid transformation in the British economy and society.

Previously, large industries had to be near forests or rivers for power. The

use of coal-fuelled engines allowed them to be placed in large urban centres.

These new factories proved far more efficient at producing goods than the cottage industry of a previous era. These manufactured goods were sold around the world, and

raw materials and luxury goods were imported to Britain.

Agriculture - мajor advances in farming made agriculture more

productive and freed up people to work in industry. The British Agricultural

Revolution included innovations in technology such as Jethro Tull's seed drill

which allowed greater yields, the process of enclosure, which had been altering

rural society since the Middle Ages, became unstoppable. The new mechanisation

needed much larger fields — the layout of the British countryside with the

patchwork of fields divided by hedgerows that we see today.

The loss of

some of the American Colonies in

the American War of Independence was

regarded as a national disaster and was seen by some foreign observers as

heralding the end of Britain as a great power.

In Europe, the wars with France dragged on for nearly a quarter of a century, 1793-1815. Victory over Napoleon at the Battle of Trafalgar (1805) and the Battle of Waterloo (1815) under Admiral Lord Nelson and the Duke of Wellington brought a sense of triumphalism and political reaction.

In Europe, the wars with France dragged on for nearly a quarter of a century, 1793-1815. Victory over Napoleon at the Battle of Trafalgar (1805) and the Battle of Waterloo (1815) under Admiral Lord Nelson and the Duke of Wellington brought a sense of triumphalism and political reaction.

|

| The Battle of Trafalgar by J. M. W. Turner (oil on canvas, 1822–1824) combines events from several moments during the battle |

| Battle of Waterloo by William Sadler |

THE CHRONOLOGY OF THE PERIOD:

1689 - Parliament draws up the Declaration of Right detailing the unconstitutional acts of King James II. James' daughter and her husband, his nephew, become joint sovereigns of Britain as King William III and Queen Mary II. Parliament passes the Bill of Rights. Toleration Act grants rights to Trinitarian Protestant dissenters. Catholic forces loyal to James II land in Ireland from France and lay siege to Londonderry

1690 - King William defeats the Irish and French armies of his father-in-law at the Battle of the Boyne in Ireland

1691 - The Treaty of Limerick allows Cathloics in Ireland to exercise their religion freely, but severe penal laws soon follow. The French War begins

1692 - The Glencoe Massacre occurs

1694 - Death of Queen Mary; King William now rules alone. Foundation of the Bank of England. Triennial Act sets the maximum duration of a parliament to three years

1695 - Lapse of the Licensing Act

1690 - King William defeats the Irish and French armies of his father-in-law at the Battle of the Boyne in Ireland

1691 - The Treaty of Limerick allows Cathloics in Ireland to exercise their religion freely, but severe penal laws soon follow. The French War begins

1692 - The Glencoe Massacre occurs

1694 - Death of Queen Mary; King William now rules alone. Foundation of the Bank of England. Triennial Act sets the maximum duration of a parliament to three years

1695 - Lapse of the Licensing Act

1697 - Peace of Ryswick between the allied powers of the League of Augsburg and France ends the French War. Civil List Act votes funds for the maintenance of the Royal Household

1701 - The Act of Settlement settles the Royal Succession on the Protestant descendants of Sophia of Hanover. Death of the former King James II in exile in France. The French king recognizes James II's son as "King James III". King William forms a grand alliance between England, Holland and Austria to prevent the union of the Spanish and French crowns. The War of the Spanish Succession breaks out in Europe over the vacant throne

1702 - Death of King William III in a riding accident. He is succeeded by his sister-in-law, Queen Anne. England declares war on France. Elections to be held every seven years

1702 - Death of King William III in a riding accident. He is succeeded by his sister-in-law, Queen Anne. England declares war on France. Elections to be held every seven years

1707: Acts of Union by the Parliament of Scotland and the Parliament of England to put into effect the terms of the Treaty of Union that had been agreed on 22 July 1706, following negotiation between commissioners representing the parliaments of the two countries. The Acts joined the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland (previously separate states, with separate legislatures but with the same monarch) into a single United Kingdom of Great Britain.

1717 - Townshend is dismissed from government by George I, causing Walpole to resign. The Whig party is split. Convocation is suspended

1719 - South Sea Bubble bursts, leaving many investors ruined after speculating with stock of the 'South Sea Company'

1721 - Sir Robert Walpole returns to government as First Lord of the Treasury. He remains in office until 1742 and effectively becomes Britain's first Prime Minister

1722 - Death of the Duke of Marlborough. The Jacobite 'Atterbury Plot' is hatched

1726 - First circulating library in Britain opens in Edinburgh. Jonathan Swift publishes his 'Gulliver's Travels'

1727 - Death of great British scientist, Sir Isaac Newton and of King George I (in Hanover). The latter is succeeded by his son as King George II

1729 - Alexander Pope publishes his ' Dunciad'

1730 - A split occurs between Walpole and Townshend

1732 - A royal charter is granted for the founding of Georgia in America

1733 - The 'Excise Crisis' occurs and Walpole is forced to abandon his plans to reorganise the customs and excise

1737 - Death of King George II's wife, Queen Caroline

1719 - South Sea Bubble bursts, leaving many investors ruined after speculating with stock of the 'South Sea Company'

1721 - Sir Robert Walpole returns to government as First Lord of the Treasury. He remains in office until 1742 and effectively becomes Britain's first Prime Minister

1722 - Death of the Duke of Marlborough. The Jacobite 'Atterbury Plot' is hatched

1726 - First circulating library in Britain opens in Edinburgh. Jonathan Swift publishes his 'Gulliver's Travels'

1727 - Death of great British scientist, Sir Isaac Newton and of King George I (in Hanover). The latter is succeeded by his son as King George II

1729 - Alexander Pope publishes his ' Dunciad'

1730 - A split occurs between Walpole and Townshend

1732 - A royal charter is granted for the founding of Georgia in America

1733 - The 'Excise Crisis' occurs and Walpole is forced to abandon his plans to reorganise the customs and excise

1737 - Death of King George II's wife, Queen Caroline

1738 - John and Charles Wesley start the Methodist movement in Britain

1739 - Britain goes to war with Spain in the 'War of Jenkins' Ear'. The cause: Captain Jenkins' ear was claimed to have been cut off during a Naval Skirmish

1740 - Commencement of the War of Austrian Succession in Europe

1742 - Walpole resigns as Prime Minister

1743 - George II leads British troops into battle at Dettingen in Bavaria

1739 - Britain goes to war with Spain in the 'War of Jenkins' Ear'. The cause: Captain Jenkins' ear was claimed to have been cut off during a Naval Skirmish

1740 - Commencement of the War of Austrian Succession in Europe

1742 - Walpole resigns as Prime Minister

1743 - George II leads British troops into battle at Dettingen in Bavaria

1744 - Ministry of Pelham

1745 - Jacobite Rebellion in Scotland led by 'Bonnie Prince Charlie'. There is a Scottish victory at Prestonpans

1746 - The Duke of Cumberland crushes the Scottish Jacobites at the Battle of Culloden

1748 - The Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle brings the War of Austrian Succession to a close

1751 - Death of Frederick, Prince of Wales. His son, Prince George, becomes heir to the throne

1752 - Adoption of the Gregorian Calendar in Britain

1753 - Parliament passes the Jewish Naturalization Bill

1754 - The ministry of Newcastle

1756 - Britain, allied with Prussia, declares war against France and her allies, Austria and Russia. The Seven Years' War begins

1745 - Jacobite Rebellion in Scotland led by 'Bonnie Prince Charlie'. There is a Scottish victory at Prestonpans

1746 - The Duke of Cumberland crushes the Scottish Jacobites at the Battle of Culloden

1748 - The Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle brings the War of Austrian Succession to a close

1751 - Death of Frederick, Prince of Wales. His son, Prince George, becomes heir to the throne

1752 - Adoption of the Gregorian Calendar in Britain

1753 - Parliament passes the Jewish Naturalization Bill

1754 - The ministry of Newcastle

1756 - Britain, allied with Prussia, declares war against France and her allies, Austria and Russia. The Seven Years' War begins

1757 - The Pitt-Newcastle ministry. Robert Clive wins the Battle of Plassey and secures the Indian province of Bengal for Britain. William Pitt becomes Prime Minister

1759 - Wolfe captures Quebec and expels the French from Canada

1760 - Death of King George II. He is succeeded by his grandson as George III

1761 - Laurence Sterne publishes his 'Tristram Shandy'

1762 - The Earl of Bute is appointed Prime Minister. He becomes very unpopular and employs a bodyguard

1763 - Peace of Paris ends the Seven Years' War. Grenville ministry.

1765 - Rockingham ministry. The American Stamp Act raises taxes in the colonies in an attempt to make their defence self-financing

1766 - Chatham ministry. Repeal of the American Stamp Act

1768 - Grafton ministry. The Middlesex Election Crisis occurs

1769 - James Watt patents the Steam Engine

1759 - Wolfe captures Quebec and expels the French from Canada

1760 - Death of King George II. He is succeeded by his grandson as George III

1761 - Laurence Sterne publishes his 'Tristram Shandy'

1762 - The Earl of Bute is appointed Prime Minister. He becomes very unpopular and employs a bodyguard

1763 - Peace of Paris ends the Seven Years' War. Grenville ministry.

1765 - Rockingham ministry. The American Stamp Act raises taxes in the colonies in an attempt to make their defence self-financing

1766 - Chatham ministry. Repeal of the American Stamp Act

1768 - Grafton ministry. The Middlesex Election Crisis occurs

1769 - James Watt patents the Steam Engine

1769-70 - Captain James Cook's first voyage to explore the Pacific

1770 - Lord North begins service as Prime Minister. The Falkland Island Crisis occurs. Edmund Burke publishes his 'Thoughts on the Present Discontents'

1771 - The Encyclopedia Britannica is first published

1770 - Lord North begins service as Prime Minister. The Falkland Island Crisis occurs. Edmund Burke publishes his 'Thoughts on the Present Discontents'

1771 - The Encyclopedia Britannica is first published

1773 - American colonists protest at the East India Company's monopoly over tea exports to the colonies, at the so-called 'Boston Tea Party'. The World's first cast-iron bridge is constructed over the River Severn at Coalbrookdale

1774 - Parliament passes the Coercive Acts in retaliation for the 'Boston Tea Party'

1775 - American War of Independence begins when colonists fight British troops at Lexington. James Watt further develops his steam engine

1776 - On 4th July, the American Congress passes their Declaration of Independence from Britain. Edward Gibbons' publishes his 'Decline and Fall' and Adam Smith, his 'Wealth of Nations'

1779 - The rise of Wyvill's Association Movement

1780 - The Gordon Riots develop from a procession to petition parliament against the Catholic Relief Act

1781 - The Americans obtain a great victory of British troops at the surrender of Yorktown

1782 - End of Lord North's time as Prime Minister. He is succeeded by Rockingham in his second ministry. Ireland obtains short-lived parliament

1783 - Shelburne's ministry, followed by that of William Pitt the Younger. Britain recognises American independence at the Peace of Versailles. Fox-North coalition established

1784 - Parliament passes the East India Act

1785 - Pitt's motion for Parliamentary Reform is defeated

1786 - The Eden commercial treaty with France is drawn up

1775 - American War of Independence begins when colonists fight British troops at Lexington. James Watt further develops his steam engine

1776 - On 4th July, the American Congress passes their Declaration of Independence from Britain. Edward Gibbons' publishes his 'Decline and Fall' and Adam Smith, his 'Wealth of Nations'

1779 - The rise of Wyvill's Association Movement

1780 - The Gordon Riots develop from a procession to petition parliament against the Catholic Relief Act

1781 - The Americans obtain a great victory of British troops at the surrender of Yorktown

1782 - End of Lord North's time as Prime Minister. He is succeeded by Rockingham in his second ministry. Ireland obtains short-lived parliament

1783 - Shelburne's ministry, followed by that of William Pitt the Younger. Britain recognises American independence at the Peace of Versailles. Fox-North coalition established

1784 - Parliament passes the East India Act

1785 - Pitt's motion for Parliamentary Reform is defeated

1786 - The Eden commercial treaty with France is drawn up

1788 - George III suffers his first attack of 'madness' (caused by porphyria)

1789 - Outbreak of the French Revolution

1789 - Outbreak of the French Revolution

1790 - Edmund Burke publishes his 'Reflections on the Revolution in France'

1791 - James Boswell publishes his 'Life of Johnson' an Thomas Paine, his 'Rights of Man'

1792 - Coal gas is used for lighting for the first time. Mary Wollstonecraft publishes her 'Vindication of the Rights of Women'

1793 - Outbreak of War between Britain and France. The voluntary Board of Agriculture is set up. Commercial depression throughout Britain

1795 - The 'Speenhamland' system of outdoor relief is adopted, making wages up to equal the cost of subsistence

1796 - Vaccination against smallpox is introduced

1798 - Introduction of a tax of ten percent on incomes over £200. T.R. Malthus publishes his 'Essay on Population'

1799 - Trade Unions are suppressed. Napoleon is appointed First Consul in France

1799-1801 - Commercial boom in Britain

1800 - Act of Union with Ireland unites Parliaments of England and Ireland

1801 - Close of Pitt the Younger's Ministry. The first British Census is undertaken

1791 - James Boswell publishes his 'Life of Johnson' an Thomas Paine, his 'Rights of Man'

1792 - Coal gas is used for lighting for the first time. Mary Wollstonecraft publishes her 'Vindication of the Rights of Women'

1793 - Outbreak of War between Britain and France. The voluntary Board of Agriculture is set up. Commercial depression throughout Britain

1795 - The 'Speenhamland' system of outdoor relief is adopted, making wages up to equal the cost of subsistence

1796 - Vaccination against smallpox is introduced

1798 - Introduction of a tax of ten percent on incomes over £200. T.R. Malthus publishes his 'Essay on Population'

1799 - Trade Unions are suppressed. Napoleon is appointed First Consul in France

1799-1801 - Commercial boom in Britain

1800 - Act of Union with Ireland unites Parliaments of England and Ireland

1801 - Close of Pitt the Younger's Ministry. The first British Census is undertaken

1802 - Peace with France is established. Peel introduces the first factory legislation

1803 - Beginning of the Napoleonic Wars. Britain declares war on France. Parliament passes the General Enclosure Act, simplifying the process of enclosing common land

1805 - Nelson destroys the French and Spanish fleets at the Battle of Trafalgar, but is killed in the process

1808-14 - Peninsular War to drive the French out of Spain

1809-10 - Commercial boom in Britain

1803 - Beginning of the Napoleonic Wars. Britain declares war on France. Parliament passes the General Enclosure Act, simplifying the process of enclosing common land

1805 - Nelson destroys the French and Spanish fleets at the Battle of Trafalgar, but is killed in the process

1808-14 - Peninsular War to drive the French out of Spain

1809-10 - Commercial boom in Britain

1810 - Final illness of George III begins

1811 - Depression caused by Orders of Council. There are Luddite disturbances in Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire. The King's illness leads to his son, the Prince of Wales, becoming Regent

1812 - Prime Minister Spencer Perceval is assassinated in the House of Commons by a disgruntled bankrupt

1813 - Jane Austen's 'Pride and Prejudice' is published. The monopolies of the East India Company are abolished

1811 - Depression caused by Orders of Council. There are Luddite disturbances in Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire. The King's illness leads to his son, the Prince of Wales, becoming Regent

1812 - Prime Minister Spencer Perceval is assassinated in the House of Commons by a disgruntled bankrupt