After a period

of exploration sponsored by major European nations, the first

successful English settlement was established in 1607. Europeans brought

horses, cattle, and hogs to the Americas and, in turn, took back to Europe

maize, turkeys, potatoes, tobacco, beans, and squash. Many

explorers and early settlers died after being exposed to new diseases in the

Americas. The effects of new Eurasian diseases carried by the colonists,

especially smallpox and measles, were much worse for the Native Americans, as

they had no immunity to them. They suffered epidemics and died

in very large numbers, usually before large-scale European settlement began.

Their societies were disrupted and hollowed out by the scale of deaths.

1. Spanish, Dutch, and French colonization

The first Europeans to arrive in North

America — at least the first for whom there is solid evidence — were Norse,

traveling west from Greenland, where Erik the Red had founded a settlement

around the year 985. In 1001 his son Leif is thought to have explored the northeast

coast of what is now Canada and spent at least one winter there.

While Norse sagas suggest that Viking sailors explored the Atlantic coast of North America down as far as the Bahamas, such claims remain unproven. In 1963, however, the ruins of some Norse houses dating from that era were discovered at L’Anse-aux-Meadows in northern Newfoundland, thus supporting at least some of the saga claims.

In 1497, just five years after Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean looking for a western route to Asia, a Venetian sailor named John Cabot arrived in Newfoundland on a mission for the British king. Although quickly forgotten, Cabot’s journey was later to provide the basis for British claims to North America. It also opened the way to the rich fishing grounds off George’s Banks, to which European fishermen, particularly the Portuguese, were soon making regular visits.

While Norse sagas suggest that Viking sailors explored the Atlantic coast of North America down as far as the Bahamas, such claims remain unproven. In 1963, however, the ruins of some Norse houses dating from that era were discovered at L’Anse-aux-Meadows in northern Newfoundland, thus supporting at least some of the saga claims.

In 1497, just five years after Christopher Columbus landed in the Caribbean looking for a western route to Asia, a Venetian sailor named John Cabot arrived in Newfoundland on a mission for the British king. Although quickly forgotten, Cabot’s journey was later to provide the basis for British claims to North America. It also opened the way to the rich fishing grounds off George’s Banks, to which European fishermen, particularly the Portuguese, were soon making regular visits.

A. Spanish colonization

Spanish explorers were the first Europeans with Christopher Columbus' second expedition, to reach Puerto Rico on November 19, 1493; others reached Florida in 1513. Columbus never saw the mainland of the future United States, but the first explorations of it were launched from the Spanish possessions that he helped establish. The first of these took place in 1513 when a group of men under Juan Ponce de León landed on the Florida coast near the present city of St. Augustine.

With the conquest of Mexico in 1522,

the Spanish further solidified their position in the Western Hemisphere. The

ensuing discoveries added to Europe’s knowledge of what was now named America

— after the Italian Amerigo Vespucci, who wrote a widely popular account of

his voyages to a “New World.” By 1529 reliable maps of the Atlantic coastline

from Labrador to Tierra del Fuego had been drawn up, although it would take

more than another century before hope of discovering a “Northwest Passage” to

Asia would be completely abandoned.

Among the most significant early

Spanish explorations was that of Hernando De Soto, a veteran conquistador who

had accompanied Francisco Pizarro in the conquest of Peru. Leaving Havana in

1539, De Soto’s expedition landed in Florida and ranged through the southeastern

United States as far as the Mississippi River in search of riches.

Another Spaniard, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, set out from Mexico in 1540 in search of the mythical Seven Cities of Cibola. Coronado’s travels took him to the Grand Canyon and Kansas, but failed to reveal the gold or treasure his men sought. However, his party did leave the peoples of the region a remarkable, if unintended, gift: Enough of his horses escaped to transform life on the Great Plains. Within a few generations, the Plains Indians had become masters of horsemanship, greatly expanding the range of their activities.

Small Spanish settlements eventually grew to become important cities, such as San Antonio, Texas; Albuquerque, New Mexico; Tucson, Arizona; Los Angeles, California; and San Francisco, California.

Spanish explorers were the first Europeans with Christopher Columbus' second expedition, to reach Puerto Rico on November 19, 1493; others reached Florida in 1513. Columbus never saw the mainland of the future United States, but the first explorations of it were launched from the Spanish possessions that he helped establish. The first of these took place in 1513 when a group of men under Juan Ponce de León landed on the Florida coast near the present city of St. Augustine.

|

| Columbus landed in Puerto Rico 1492 |

|

| Spaniards settled in Florida |

Another Spaniard, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, set out from Mexico in 1540 in search of the mythical Seven Cities of Cibola. Coronado’s travels took him to the Grand Canyon and Kansas, but failed to reveal the gold or treasure his men sought. However, his party did leave the peoples of the region a remarkable, if unintended, gift: Enough of his horses escaped to transform life on the Great Plains. Within a few generations, the Plains Indians had become masters of horsemanship, greatly expanding the range of their activities.

Small Spanish settlements eventually grew to become important cities, such as San Antonio, Texas; Albuquerque, New Mexico; Tucson, Arizona; Los Angeles, California; and San Francisco, California.

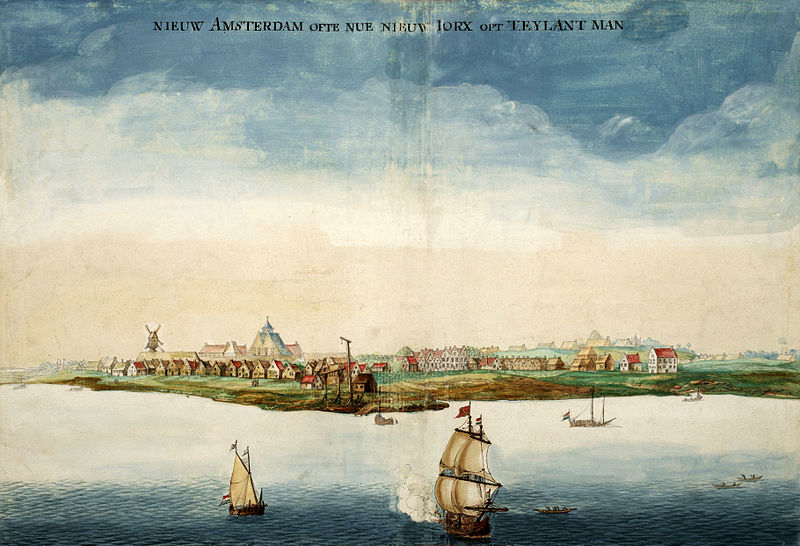

New

Netherland was a 17th-century colonial province of the Seven United Netherlands that

was located on the East Coast of North America. The claimed

territories extended from the Delmarva Peninsula to

extreme southwestern Cape Cod, while the more limited settled areas are now part of

the Mid-Atlantic

States of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Connecticut, with small

outposts in Pennsylvania and Rhode Island.

The colony was conceived as a private

business venture to exploit the North

American fur trade. During its first decades, New Netherland was

settled rather slowly, partially as a result of policy mismanagement by the Dutch West India Company (WIC)

and partially as a result of conflicts with Native

Americans. The settlement of New Sweden encroached on its southern flank,

while its northern border was re-drawn to accommodate an expanding New England. During the 1650s, the

colony experienced dramatic growth and became a major port for trade in the North Atlantic. The

surrender of Fort

Amsterdam to England in 1664 was formalized in 1667,

contributing to the Second

Anglo–Dutch War. In 1673, the Dutch re-took the area but

relinquished it under the Second Treaty of Westminster ending the Third

Anglo-Dutch War the

next year.

The inhabitants of New Netherland were Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans, the last chiefly imported as enslaved laborers. Descendants of the original settlers played a prominent role in colonial America. For two centuries, New Netherland Dutch culture characterized the region (today's Capital District around Albany, the Hudson Valley, western Long Island, northeastern New Jersey, and New York City).

The colony, which was taken over by Britain in 1664, left an enduring legacy on American cultural and political life. This includes secular broad-mindedness and mercantile pragmatism in the city as well as rural traditionalism in the countryside (typified by the story of Rip Van Winkle). Notable Americans of Dutch descent include Martin Van Buren, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt and the Frelinghuysens.

The inhabitants of New Netherland were Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans, the last chiefly imported as enslaved laborers. Descendants of the original settlers played a prominent role in colonial America. For two centuries, New Netherland Dutch culture characterized the region (today's Capital District around Albany, the Hudson Valley, western Long Island, northeastern New Jersey, and New York City).

The colony, which was taken over by Britain in 1664, left an enduring legacy on American cultural and political life. This includes secular broad-mindedness and mercantile pragmatism in the city as well as rural traditionalism in the countryside (typified by the story of Rip Van Winkle). Notable Americans of Dutch descent include Martin Van Buren, Theodore Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt and the Frelinghuysens.

C. French colonization - while the Spanish were pushing up from

the south, the northern portion of the present-day United States was slowly

being revealed through the journeys of men such as Giovanni da Verrazano. A Florentine who sailed for the

French, Verrazano made landfall in North Carolina in 1524, then sailed north

along the Atlantic Coast past what is now New York harbor.

A decade later, the Frenchman Jacques Cartier set sail with the hope — like the other Europeans before him — of finding a sea passage to Asia. Cartier’s expeditions along the St.Lawrence River laid the foundation for the French claims to North America, which were to last until 1763.

New France was the area colonized by France from 1534 to 1763. There were few permanent settlers outside Quebec and Acadia, but the French had far-reaching trading relationships with Native Americans throughout the Great Lakes and Midwest. French villages along the Mississippi and Illinois rivers were based in farming communities that served as a granary for Gulf Coast settlements. The French established plantations in Louisiana along with settling New Orleans, Mobile and Biloxi.

A decade later, the Frenchman Jacques Cartier set sail with the hope — like the other Europeans before him — of finding a sea passage to Asia. Cartier’s expeditions along the St.Lawrence River laid the foundation for the French claims to North America, which were to last until 1763.

Following the collapse of their first

Quebec colony in the 1540s, French Huguenots attempted to settle the northern

coast of Florida two decades later. The

Spanish, viewing the French as a threat to their trade route along the Gulf

Stream, destroyed the colony in 1565. Ironically,

the leader of the Spanish forces, Pedro Menéndez, would soon establish a town

not far away — St. Augustine. It was the first permanent European settlement in what would

become the United States.

New France was the area colonized by France from 1534 to 1763. There were few permanent settlers outside Quebec and Acadia, but the French had far-reaching trading relationships with Native Americans throughout the Great Lakes and Midwest. French villages along the Mississippi and Illinois rivers were based in farming communities that served as a granary for Gulf Coast settlements. The French established plantations in Louisiana along with settling New Orleans, Mobile and Biloxi.

The Wabanaki Confederacy were

military allies of New France through the four French and Indian Wars while the

British colonies were allied with the Iroquois Confederacy. During

the French and Indian War – the

North American theater of the Seven

Years' War – New England fought successfully against French Acadia. The British

removed Acadians from Acadia (Nova

Scotia) and replaced them with New England Planters. Eventually, some Acadians resettled in Louisiana,

where they developed a distinctive rural Cajun culture

that still exists. They became American citizens in 1803 with the Louisiana

Purchase. Other French villages along the Mississippi and Illinois rivers were

absorbed when the Americans started arriving after 1770, or settlers moved west

to escape them. French

influence and language in New

Orleans, Louisiana and the Gulf Coast was more enduring; New

Orleans was notable for its large population of free people of color before

the Civil War.

2. British colonization

The great wealth that

poured into Spain from the colonies in Mexico, the Caribbean, and Peru provoked

great interest on the part of the other European powers. Emerging maritime

nations such as England, drawn in part by Francis Drake’s successful raids on

Spanish treasure ships, began to take an interest in the New World.

In 1578 Humphrey Gilbert,

the author of a treatise on the search for the Northwest Passage, received a

patent from Queen Elizabeth to colonize the “heathen and barbarous landes” in

the New World that other European nations had not yet claimed. It would be five

years before his efforts could begin. When he was lost at sea, his half-brother,

Walter Raleigh, took up the mission.

In 1585 Raleigh

established the first British colony in North America, on Roanoke Island off

the coast of North Carolina. It was later abandoned, and a second effort two

years later also proved a failure. It would be 20 years before the British would

try again. This time — at Jamestown in 1607 — the colony would succeed, and

North America would enter a new era.

A. Early settlements - the early 1600s saw the

beginning of a great tide of emigration from Europe to North America. Spanning

more than three centuries, this movement grew from a trickle of a few hundred English

colonists to a flood of millions of newcomers. Impelled by powerful and diverse

motivations, they built a new civilization on the northern part of the

continent.

The first English

immigrants to what is now the United States crossed the Atlantic long after

thriving Spanish colonies had been established in Mexico, the West Indies,

and South America. Like all early travelers to the New World, they came in

small, overcrowded ships. During their six- to 12-week voyages, they lived on

meager rations. Many died of disease, ships were often battered by storms, and

some were lost at sea.

Most European emigrants

left their homelands to escape political oppression, to seek the freedom to

practice their religion, or to find opportunities denied them at home. Between

1620 and 1635, economic difficulties swept England. Many people could not find

work. Even skilled artisans could earn little more than a bare living. Poor crop

yields added to the distress. In addition, the Commercial Revolution had

created a burgeoning textile industry, which demanded an ever-increasing supply

of wool to keep the looms running. Landlords enclosed farmlands and evicted the

peasants in favor of sheep cultivation. Colonial expansion became an outlet for

this displaced peasant population.

The colonists’ first

glimpse of the new land was a vista of dense woods. The settlers might

not have survived had it not been for the help of friendly Indians, who taught

them how to grow native plants — pumpkin, squash, beans, and corn. In addition,

the vast, virgin forests, extending nearly 2,100 kilometers along the Eastern

seaboard, proved a rich source of game and firewood. They also provided abundant

raw materials used to build houses, furniture, ships, and profitable items for

export.

Although the new continent

was remarkably endowed by nature, trade with Europe was vital for articles the

settlers could not produce. The coast served the immigrants well. The whole

length of shore provided many inlets and harbors. Only two areas — North

Carolina and southern New Jersey — lacked harbors for ocean-going vessels.

Majestic rivers — the

Kennebec, Hudson, Delaware, Susquehanna, Potomac, and numerous others — linked

lands between the coast and the Appalachian Mountains with the sea. Only one

river, however, the St.Lawrence — dominated by the French in Canada — offered a

water passage to the Great Lakes and the heart of the continent. Dense forests,

the resistance of some Indian tribes, and the formidable barrier of the

Appalachian Mountains discouraged settlement beyond the coastal plain. Only

trappers and traders ventured into the wilderness. For the first hundred years

the colonists built their settlements compactly along the coast. Political considerations

influenced many people to move to America. In the 1630s, arbitrary rule by

England’s Charles I gave impetus to the migration. The subsequent revolt and

triumph of Charles’ opponents under Oliver Cromwell in the 1640s led many

cavaliers — “king’s men” — to cast their lot in Virginia. In the German-speaking

regions of Europe, the oppressive policies of various petty princes —

particularly with regard to religion — and the devastation caused by a long

series of wars helped swell the movement to America in the late 17th and 18th

centuries.

The journey entailed

careful planning and management, as well as considerable expense and

risk. Settlers had to be transported nearly 5,000 kilometers across the sea. They

needed utensils, clothing, seed, tools, building materials, livestock, arms,

and ammunition. In contrast to the colonization policies of other countries and

other periods, the emigration from England was not directly sponsored by the

government but by private groups of individuals whose chief motive was profit.

B. Major colonies - the strip of land along the eastern seacoast was settled primarily by English colonists in the 17th century along with much smaller numbers of Dutch and Swedes. Colonial America was defined by a severe labor shortage that employed forms of unfree labor such as slavery and indentured servitude and by a British policy of benign neglect (salutary neglect). Over half of all European immigrants to Colonial America arrived as indentured servants. Salutary neglect permitted the development of an American spirit distinct from that of its European founders.

JAMESTOWN - the first of the British

colonies to take hold in North America was Jamestown. On the basis of a charter

which King James I granted to the Virginia (or London) Company, a group of

about 100 men set out for the Chesapeake Bay in 1607. Seeking to avoid conflict

with the Spanish, they chose a site about 60 kilometers up the James River from the

bay.

Made up of townsmen and adventurers

more interested in finding gold than farming, the group was unequipped by

temperament or ability to embark upon a completely new life in the

wilderness. Among them, Captain John Smith emerged as the dominant

figure. Despite quarrels, starvation, and Native-American attacks, his ability

to enforce discipline held the little colony together through its first year.

In 1609 Smith returned to

England, and in his absence, the colony descended into anarchy. During the

winter of 1609-1610, the majority of the colonists succumbed to disease. Only 60

of the original 300 settlers were still alive by May 1610. That same year, the

town of Henrico (now Richmond) was established farther up the James River.

It was not long, however,

before a development occurred that revolutionized Virginia’s economy. In 1612

John Rolfe began cross-breeding imported tobacco seed from the West Indies

with native plants and produced a new variety that was pleasing to European

taste. The first shipment of this tobacco reached London in 1614. Within a decade

it had become Virginia’s chief source of revenue.

Prosperity did not come

quickly, however, and the death rate from disease and Indian attacks remained

extraordinarily high. Between 1607 and 1624 approximately 14,000 people

migrated to the colony, yet only 1,132 were living there in 1624. On recommendation of a royal

commission, the king dissolved the Virginia Company, and made it a royal

colony that year.

Jamestown

languished for decades until a new wave of settlers arrived in the late 17th

century and established commercial agriculture based on tobacco. Between the

late 1610s and the Revolution, the British shipped an estimated 50,000 convicts

to their American colonies.

A severe instance of conflict was the 1622 Powhatan uprising in Virginia in which Native Americans killed hundreds of English settlers. The largest conflicts between Native Americans and English settlers in the 17th century were King Philip's War in New England and the Yamasee War in South Carolina.

A severe instance of conflict was the 1622 Powhatan uprising in Virginia in which Native Americans killed hundreds of English settlers. The largest conflicts between Native Americans and English settlers in the 17th century were King Philip's War in New England and the Yamasee War in South Carolina.

|

| The Indian massacre of Jamestown settlers in 1622. Soon the colonists in the South feared all natives as enemies. |

New England was initially settled primarily by Puritans. The Pilgrims established a settlement in 1620 at Plymouth Colony, which was followed by the establishment of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630. The Middle Colonies, consisting of the present-day states of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware, were characterized by a large degree of diversity. The first attempted English settlement south of Virginia was the Province of Carolina, with Georgia Colony – the last of the Thirteen Colonies – established in 1733.

MASSACHUSETTS - during the religious

upheavals of the 16th century, a body of men and women called Puritans sought

to reform the Established Church of England from within. Essentially, they demanded

that the rituals and structures associated with Roman Catholicism be replaced

by simpler Calvinist Protestant forms of faith and worship. Their reformist

ideas, by destroying the unity of the state church, threatened to divide the

people and to undermine royal authority.

In 1607 a small group of

Separatists — a radical sect of Puritans who did not believe the Established

Church could ever be reformed — departed for Leyden, Holland, where the Dutch

granted them asylum. However, the Calvinist Dutch restricted them mainly to

low-paid laboring jobs. Some members of the congregation grew dissatisfied with

this discrimination and resolved to emigrate to the New World.

In 1620, a group of Leyden

Puritans secured a land patent from the Virginia Company. Numbering 101, they

set out for Virginia on the Mayflower. A storm sent them far north and

they landed in New England on Cape Cod. Believing themselves outside the jurisdiction of any organized government, the men

drafted a formal agreement to abide by “just and equal laws” drafted by leaders

of their own choosing. This was the Mayflower Compact.

A new wave of immigrants arrived on the shores of Massachusetts Bay in 1630 bearing a grant from King Charles I to establish a colony. Many of them were Puritans whose religious practices were increasingly prohibited in England. Their leader, John Winthrop, urged them to create a “city upon a hill” in the New World — a place where they would live in strict accordance with their religious beliefs and set an example for all of Christendom.

|

| The Mayflower, which transported Pilgrims to the New World. During the first winter at Plymouth, about half of the Pilgrims died. |

Under the charter’s

provisions, power rested with the General Court, which was made up of “free men” required to be

members of the Puritan, or Congregational, Church. This guaranteed that the

Puritans would be the dominant political as well as religious force in the

colony. The General Court elected the governor, who for most of the next generation

would be John Winthrop.

The rigid orthodoxy of the

Puritan rule was not to everyone’s liking. One of the first to challenge the

General Court openly was a young clergyman named Roger Williams, who objected

to the colony’s seizure of Indian lands and advocated separation of church and

state. Another dissenter, Anne Hutchinson, challenged key doctrines of

Puritan theology. Both they and their followers were banished.

Williams purchased land

from the Narragansett Indians in what is now Providence, Rhode Island, in

1636. In 1644, a sympathetic Puritan-controlled English Parliament gave him the

charter that established Rhode Island as a distinct colony where complete

separation of church and state as well as freedom of religion was practiced.

So-called heretics like

Williams were not the only ones who left Massachusetts. Orthodox Puritans, seeking

better lands and opportunities, soon began leaving Massachusetts Bay

Colony. News of the fertility of the Connecticut River Valley, for instance,

attracted the interest of farmers having a difficult time with poor land. By

the early 1630s, many were ready to brave the danger of Indian attack to obtain

level ground and deep, rich soil.These new communities often eliminated church membership

as a prerequisite for voting, thereby extending the franchise to ever larger

numbers of men.

At the same time, other

settlements began cropping up along the New Hampshire and Maine coasts, as

more and more immigrants sought the land and liberty the New World seemed to

offer.

NEW

NETHERLAND AND MARYLAND - hired by the Dutch East

India Company, Henry Hudson in 1609 explored the area around what is now New

York City and the river that bears his name, to a point probably north of

present-day Albany, New York. Subsequent Dutch voyages laid the basis for their

claims and early settlements in the area.

As with the French to the

north, the first interest of the Dutch was the fur trade. To this end, they

cultivated close relations with the Five Nations of the Iroquois, who were the

key to the heartland from which the furs came. In 1617 Dutch settlers built a

fort at the junction of the Hudson and the Mohawk Rivers, where Albany now

stands.

Settlement on the island

of Manhattan began in the early 1620s. In 1624, the island was purchased from

local Native Americans for the reported price of $24. It was promptly renamed

New Amsterdam.

In order to attract

settlers to the Hudson River region, the Dutch encouraged a type of feudal

aristocracy, known as the “patroon” system. The first of these huge

estates were established in 1630 along the Hudson River. Under the patroon system,

any stockholder, or patroon, who could bring 50 adults to his estate over a

four-year period was given a 25-kilometer river-front plot, exclusive fishing

and hunting privileges, and civil and criminal jurisdiction over his lands. In

turn, he provided livestock, tools, and buildings. The tenants paid the patroon

rent and gave him first option on surplus crops.

Further to the south, a

Swedish trading company with ties to the Dutch attempted to set up its first

settlement along the Delaware River three years later. Without the resources

to consolidate its position, New Sweden was gradually absorbed into New

Netherland, and later, Pennsylvania and Delaware.

In 1632 the Catholic

Calvert family obtained a charter for land north of the Potomac River from

King Charles I in what became known as Maryland. As the charter did not expressly

prohibit the establishment of non-Protestant churches, the colony became a

haven for Catholics. Maryland’s first town, St.Mary’s, was established in 1634

near where the Potomac River flows into the Chesapeake Bay.

While establishing a

refuge for Catholics, who faced increasing persecution in Anglican England,

the Calverts were also interested in creating profitable estates. To this end, and to avoid trouble with

the British government, they also encouraged Protestant immigration.

Maryland’s royal charter

had a mixture of feudal and modern elements. On the one hand the Calvert family

had the power to create manorial estates. On the other, they could only make

laws with the consent of freemen (property holders). They found that in order to

attract settlers — and make a profit from their holdings — they had to offer

people farms, not just tenancy on manorial estates. The number of independent

farms grew in consequence. Their owners demanded a voice in the affairs of the

colony. Maryland’s first legislature met in 1635.

C. Colonial-indian relations - by 1640 the British had

solid colonies established along the New England coast and the Chesapeake

Bay. In between were the Dutch and the tiny Swedish community. To the west were

the original Americans, then called Indians.

Sometimes friendly,

sometimes hostile, the Eastern tribes were no longer strangers to the

Europeans. Although Native Americans benefited from access to new technology

and trade, the disease and thirst for land that the early settlers also brought

posed a serious challenge to their long-established way of life.

At first, trade with the

European settlers brought advantages: knives, axes, weapons, cooking

utensils, fishhooks, and a host of other goods. Those Indians who traded initially

had significant advantage over rivals who did not. In response to European

demand, tribes such as the Iroquois began to devote more attention to fur

trapping during the 17th century. Furs and pelts provided tribes the means to

purchase colonial goods until late into the 18th century.

Early

colonial-Native-American relations were an uneasy mix of cooperation and

conflict. On the one hand, there were the exemplary relations that prevailed

during the first half century of Pennsylvania’s existence. On the other were a

long series of setbacks, skirmishes, and wars, which almost invariably resulted

in an Indian defeat and further loss of land. The first of the important

Native- American uprisings occurred in Virginia in 1622, when some 347 whites

were killed, including a number of missionaries who had just recently come to

Jamestown.

White settlement of the

Connecticut River region touched off the Pequot War in 1637.

In 1675 King Philip, the son of the native chief who had made the original peace with the Pilgrims in 1621, attempted to unite the tribes of southern New England against further European encroachment of their lands. In the struggle, however, Philip lost his life and many Indians were sold into servitude. The steady influx of settlers into the backwoods regions of the Eastern colonies disrupted Native-American life. As more and more game was killed off, tribes were faced with the difficult choice of going hungry, going to war, or moving and coming into conflict with other tribes to the west.

In 1675 King Philip, the son of the native chief who had made the original peace with the Pilgrims in 1621, attempted to unite the tribes of southern New England against further European encroachment of their lands. In the struggle, however, Philip lost his life and many Indians were sold into servitude. The steady influx of settlers into the backwoods regions of the Eastern colonies disrupted Native-American life. As more and more game was killed off, tribes were faced with the difficult choice of going hungry, going to war, or moving and coming into conflict with other tribes to the west.

The Iroquois, who

inhabited the area below lakes Ontario and Erie in northern New York and

Pennsylvania, were more successful in resisting European advances. In 1570

five tribes joined to form the most complex Native-American nation of its time,

the “Ho-De-No-Sau- Nee,” or League of the Iroquois. The league was run by a

council made up of 50 representatives from each of the five member tribes. The

council dealt with matters common to all the tribes, but it had no say in how

the free and equal tribes ran their day-to-day affairs. No tribe was allowed to

make war by itself. The council passed laws to deal with crimes such as murder.

The Iroquois League was a

strong power in the 1600s and 1700s. It traded furs with the British and sided

with them against the French in the war for the dominance of America between

1754 and 1763. The British might not have won that war otherwise.

The Iroquois League stayed

strong until the American Revolution. Then, for the first time, the council

could not reach a unanimous decision on whom to support. Member tribes made

their own decisions, some fighting with the British, some with the

colonists, some remaining neutral. As a result, everyone fought against the

Iroquois. Their losses were great and the league never recovered.

D. Second generation of British colonies - the religious and civil

conflict in England in the mid-17th century limited immigration, as well as the

attention the mother country paid the fledgling American colonies.

In part to provide for the

defense measures England was neglecting, the Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth,

Connecticut, and New Haven colonies formed the New England Confederation in

1643. It was the European colonists’ first attempt at regional unity.

The early history of the

British settlers reveals a good deal of contention — religious and political —

as groups vied for power and position among themselves and their

neighbors. Maryland, in particular, suffered from the bitter religious rivalries

that afflicted England during the era of Oliver Cromwell. One of the casualties

was the state’s Toleration Act, which was revoked in the 1650s. It was soon

reinstated, however, along with the religious freedom it guaranteed.

With the restoration of

King Charles II in 1660, the British once again turned their attention to North

America. Within a brief span, the first European settlements were established in the

Carolinas and the Dutch driven out of New Netherland. New proprietary colonies

were established in New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Pennsylvania.

The Dutch settlements had

been ruled by autocratic governors appointed in Europe. Over the years, the

local population had become estranged from them. As a result, when the British

colonists began encroaching on Dutch claims in Long Island and Manhattan, the

unpopular governor was unable to rally the population to their defense. New

Netherland fell in 1664. The terms of the capitulation, however, were mild: The

Dutch settlers were able to retain their property and worship as they pleased.

As early as the 1650s, the

Albemarle Sound region off the coast of what is now northern North Carolina

was inhabited by settlers trickling down from Virginia. The first proprietary

governor arrived in 1664. The first town in Albemarle, a remote area even

today, was not established until the arrival of a group of French Huguenots in

1704.

In 1670 the first

settlers, drawn from New England and the Caribbean island of Barbados, arrived

in what is now Charleston, South Carolina. An elaborate system of government, to

which the British philosopher John Locke contributed, was prepared for the new

colony. One of its prominent features was a failed attempt to create a

hereditary nobility. One of the colony’s least appealing aspects was the early

trade in Indian slaves. With time, however, timber, rice, and indigo gave

the colony a worthier economic base.

In 1681 William Penn, a

wealthy Quaker and friend of Charles II, received a large tract of land west

of the Delaware River, which became known as Pennsylvania. To help populate it,

Penn actively recruited a host of religious dissenters from England and the

continent — Quakers, Mennonites, Amish, Moravians, and Baptists.

When Penn arrived the

following year, there were already Dutch, Swedish, and English settlers living

along the Delaware River. It was there he founded Philadelphia, the “City of

Brotherly Love.”

In keeping with his faith,

Penn was motivated by a sense of equality not often found in other American

colonies at the time. Thus, women in Pennsylvania had rights long before they

did in other parts of America. Penn and his deputies also paid considerable

attention to the colony’s relations with the Delaware Indians, ensuring that

they were paid for land on which the Europeans settled.

Georgia was settled in

1732, the last of the 13 colonies to be established. Lying close to, if not

actually inside the boundaries of Spanish Florida, the region was viewed as a

buffer against Spanish incursion. But it had another unique quality: The man

charged with Georgia’s fortifications, General James Oglethorpe, was a reformer

who deliberately set out to create a refuge where the poor and former prisoners would be given new

opportunities.

The colonies

were characterized by religious diversity, with many Congregationalists in New

England, German and Dutch Reformed in the Middle Colonies, Catholics in

Maryland, and Scots-Irish Presbyterians

on the frontier. Sephardic Jews were

among early settlers in cities of New England and the South. Many immigrants

arrived as religious refugees: French Huguenots settled

in New York, Virginia and the Carolinas. Many royal officials and merchants

were Anglicans.

SETTLERS,

SLAVES, AND SERVANTS - men and women with little

active interest in a new life in America were often induced to make the move to

the New World by the skillful persuasion of promoters. William Penn, for

example, publicized the opportunities awaiting newcomers to the Pennsylvania

colony. Judges and prison authorities offered convicts a chance to migrate to

colonies like Georgia instead of serving prison sentences.

But few colonists could

finance the cost of passage for themselves and their families to make a start

in the new land. In some cases, ships’ captains received large rewards from the

sale of service contracts for poor migrants, called indentured servants, and

every method from extravagant promises to actual kidnapping was used to take on

as many passengers as their vessels could hold.

In other cases, the

expenses of transportation and maintenance were paid by colonizing agencies

like the Virginia or Massachusetts Bay Companies. In return, indentured servants

agreed to work for the agencies as contract laborers, usually for four to

seven years. Free at the end of this term, they would be given “freedom dues,”

sometimes including a small tract of land. Perhaps half the settlers living in the colonies south of New

England came to America under this system. Although most of them fulfilled their

obligations faithfully, some ran away from their employers. Nevertheless, many

of them were eventually able to secure land and set up homesteads, either in

the colonies in which they had originally settled or in neighboring ones. No

social stigma was attached to a family that had its beginning in America under

this semi-bondage. Every colony had its share of leaders who were former indentured

servants. There was one very important exception to this pattern: African

slaves. The first black Africans were brought to Virginia in 1619, just 12 years

after the founding of Jamestown. Initially, many were regarded as indentured

servants who could earn their freedom. By the 1660s, however, as the demand for

plantation labor in the Southern colonies grew, the institution of slavery began

to harden around them, and Africans were brought to America in shackles for a

lifetime of involuntary servitude.

Religiosity

expanded greatly after the First Great Awakening, a religious

revival in the 1740s led by preachers such as Jonathan Edwards and George

Whitefield. American Evangelicals affected by the Awakening added a new emphasis on

divine outpourings of the Holy Spirit and conversions that implanted within new

believers an intense love for God. Revivals encapsulated those hallmarks and

carried the newly created evangelicalism into the early republic, setting the

stage for the Second Great Awakening beginning

in the late 1790s. In the early stages, evangelicals in the South such as

Methodists and Baptists preached for religious freedom and abolition of

slavery; they converted many slaves and recognized some as preachers.

Each of the 13

American colonies had a slightly different governmental structure. Typically, a

colony was ruled by a governor appointed from London who controlled the

executive administration and relied upon a locally elected legislature to vote

taxes and make laws. By the 18th century, the American colonies were growing

very rapidly as a result of low death rates along with ample supplies of land

and food. The colonies were richer than most parts of Britain, and attracted a

steady flow of immigrants, especially teenagers who arrived as indentured

servants.

The tobacco

and rice plantations imported African slaves for

labor from the British colonies in the West Indies, and by the 1770s African

slaves comprised a fifth of the American population. The question of

independence from Britain did not arise as long as the colonies needed British

military support against the French and Spanish powers. Those threats were gone

by 1765. London regarded the American colonies as existing for the benefit of

the mother country. This policy is known as mercantilism.

3. 18-th century

NEW PEOPLES - most settlers who came to America in the 17th century were English, but there were also Dutch, Swedes, and Germans in the middle region, a few French Huguenots in South Carolina and elsewhere, slaves from Africa, primarily in the South, and a scattering of Spaniards, Italians, and Portuguese throughout the colonies.

After 1680 England ceased to

be the chief source of immigration, supplanted by Scots and “Scots-Irish”

(Protestants from Northern Ireland). In addition, tens of thousands of refugees

fled northwestern Europe to escape war, oppression, and absentee-landlordism.

By 1690 the American population had risen to a quarter of a million. From then on, it doubled every 25 years until, in 1775, it numbered more than 2.5 million. Although families occasionally moved from one colony to another, distinctions between individual colonies were marked. They were even more so among the three regional groupings of colonies.

By 1690 the American population had risen to a quarter of a million. From then on, it doubled every 25 years until, in 1775, it numbered more than 2.5 million. Although families occasionally moved from one colony to another, distinctions between individual colonies were marked. They were even more so among the three regional groupings of colonies.

NEW ENGLAND - the

northeastern New England colonies had generally thin, stony soil, relatively

little level land, and long winters, making it difficult to make a living from

farming. Turning

to other pursuits, the New Englanders harnessed waterpower and established

grain mills and sawmills. Good stands of timber encouraged shipbuilding. Excellent harbors promoted

trade, and the sea became a source of great wealth. In Massachusetts, the cod

industry alone quickly furnished a basis for prosperity.

With

the bulk of the early settlers living in villages and towns around the harbors,

many New Englanders carried on some kind of trade or business. Common

pastureland and woodlots served the needs of townspeople, who worked small

farms nearby. Compactness made possible

the village school, the village church, and the village or town hall, where

citizens met to discuss matters of common interest.

The

Massachusetts Bay Colony continued to expand its commerce. From the middle of

the 17th century onward it grew prosperous, so that Boston became one of

America’s greatest ports.

Oak

timber for ships’ hulls, tall pines for spars and masts, and pitch for the

seams of ships came from the Northeastern forests. Building their own vessels

and sailing them to ports all over the world, the shipmasters of Massachusetts

Bay laid the foundation for a trade that was to grow steadily in importance. By the end of the colonial

period, one-third of all vessels under the British flag were built in New

England. Fish, ship’s stores, and woodenware swelled the exports. New England

merchants and shippers soon discovered that rum and slaves were profitable commodities. One of their most enterprising

— if unsavory — trading practices of the time was the “triangular trade.”

Traders would purchase slaves off the coast of Africa for New England rum, then

sell the slaves in the West Indies where they would buy molasses to bring home

for sale to the local rum producers.

THE MIDDLE COLONIES - society

in the middle colonies was far more varied, cosmopolitan, and tolerant than in

New England. Under William Penn, Pennsylvania functioned smoothly and grew rapidly. By 1685, its population was

almost 9,000. The

heart of the colony was Philadelphia, a city of broad, tree-shaded streets,

substantial brick and stone houses, and busy docks. By the end of the colonial

period, nearly a century later, 30,000 people lived there, representing many

languages, creeds, and trades. Their

talent for successful business enterprise made the city one of the thriving

centers of the British Empire.

Though

the Quakers dominated in Philadelphia, elsewhere in Pennsylvania others were

well represented. Germans became the colony’s most skillful farmers. Important,

too, were cottage industries such as weaving, shoemaking, cabinetmaking, and

other crafts. Pennsylvania

was also the principal gateway into the New World for the Scots-Irish, who

moved into the colony in the early 18th century. “Bold and indigent strangers,”

as one Pennsylvania official called them, they hated the English and were

suspicious of all government. The Scots-Irish tended to settle in the

backcountry, where they cleared land and lived by hunting and subsistence

farming.

New

York best illustrated the polyglot nature of America. By 1646 the population along

the Hudson River included Dutch, French, Danes, Norwegians, Swedes, English,

Scots, Irish, Germans, Poles, Bohemians, Portuguese, and Italians. The Dutch continued to

exercise an important social and economic influence on the New York region long

after the fall of New Netherland and their integration into the British colonial

system. Their

sharp-stepped gable roofs became a permanent part of the city’s architecture,

and their merchants gave Manhattan much of its original bustling, commercial

atmosphere.

THE SOUTHERN COLONIES - in

contrast to New England and the middle colonies, the Southern colonies were

predominantly rural settlements.

By

the late 17th century, Virginia’s and Maryland’s economic and social structure

rested on the great planters and the yeoman farmers. The planters of the

Tidewater region, supported by slave labor, held most of the political power

and the best land. They

built great houses, adopted an aristocratic way of life, and kept in touch as

best they could with the world of culture overseas.

The

yeoman farmers, who worked smaller tracts, sat in popular assemblies and found

their way into political office. Their outspoken independence was a constant

warning to the oligarchy of planters not to encroach too far upon the rights

of free men.

The settlers of the Carolinas quickly learned to combine agriculture and commerce, and the marketplace became a major source of prosperity. Dense forests brought revenue: Lumber, tar, and resin from the longleaf pine provided some of the best shipbuilding materials in the world. Not bound to a single crop as was Virginia, North and South Carolina also produced and exported rice and indigo, a blue dye obtained from native plants that was used in coloring fabric. By 1750 more than 100,000 people lived in the two colonies of North and South Carolina. Charleston, South Carolina, was the region’s leading port and trading center.

In

the southern most colonies, as everywhere else, population growth in the

backcountry had special significance. German immigrants and Scots-Irish,

unwilling to live in the original Tidewater settlements where English influence

was strong, pushed inland. Those

who could not secure fertile land along the coast, or who had exhausted the

lands they held, found the hills farther west a bountiful refuge. Although their

hardships were enormous, restless settlers kept coming; by the 1730s they were

pouring into the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Soon the interior was dotted

with farms.

Living

on the edge of Native American country, frontier families built cabins, cleared

the wilderness, and cultivated maize and wheat. The men wore leather made from

the skin of deer or sheep, known as buckskin; the women wore garments of cloth

they spun at home. Their food consisted of venison, wild turkey, and fish. They had their own

amusements: great barbecues, dances, housewarmings for newly married couples,

shooting matches, and contests for making quilted making remains an American

tradition today.

SOCIETY, SCHOOLS, AND CULTURE - a significant

factor deterring the emergence of a powerful aristocratic or gentry class in

the colonies was the ability of anyone in an established colony to find a new

home on the frontier. Time after time, dominant Tidewater figures were obliged

to liberalize political policies, land-grant requirements, and religious practices

by the threat of a mass exodus to the frontier.

Of

equal significance for the future were the foundations of American education

and culture established during the colonial period. Harvard College was founded

in 1636 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Near the end of the century, the College of

William and Mary was established in Virginia. A few years later, the Collegiate School of

Connecticut, later to become Yale University, was chartered.

Even

more noteworthy was the growth of a school system maintained by governmental

authority. The

Puritan emphasis on reading directly from the Scriptures underscored the

importance of literacy. In 1647 the Massachusetts Bay Colony enacted the “Satan” Act, requiring every town having more than 50 families to establish

a grammar school (a Latin school to prepare students for college). Shortly thereafter, all the

other New England colonies, except for Rhode Island, followed its example.

The

Pilgrims and Puritans had brought their own little libraries and continued to

import books from London. And as early as the 1680s, Boston booksellers were doing

a thriving business in works of classical literature, history, politics,

philosophy, science, theology, and belles-lettres. In 1638 the first printing

press in the English colonies and the second in North America was installed at

Harvard College.

The

first school in Pennsylvania was begun in 1683. It taught reading, writing, and

keeping of accounts. Thereafter, in some fashion, every Quaker community

provided for the elementary teaching of its children. More advanced training — in

classical languages, history, and literature — was offered at the Friends

Public School, which still operates in Philadelphia as the William Penn

Charter School. The

school was free to the poor, but parents were required to pay tuition if they

were able.

In

Philadelphia, numerous private schools with no religious affiliation taught

languages, mathematics, and natural science; there were also night schools for

adults. Women were not entirely overlooked, but their educational opportunities

were limited to training in activities that could be conducted in the home. Private teachers instructed

the daughters of prosperous Philadelphians in French, music, dancing, painting,

singing, grammar, and sometimes bookkeeping.

In the 18th century, the intellectual and cultural development of Pennsylvania reflected, in large measure, the vigorous personalities of two men: James Logan and Benjamin Franklin. Logan was secretary of the colony, and it was in his fine library that young Franklin found the latest scientific works. In 1745 Logan erected a building for his collection and bequeathed both building and books to the city.

In the 18th century, the intellectual and cultural development of Pennsylvania reflected, in large measure, the vigorous personalities of two men: James Logan and Benjamin Franklin. Logan was secretary of the colony, and it was in his fine library that young Franklin found the latest scientific works. In 1745 Logan erected a building for his collection and bequeathed both building and books to the city.

Franklin

contributed even more to the intellectual activity of Philadelphia. He formed a debating club

that became the embryo of the American Philosophical Society. His endeavors also led to

the founding of a public academy that later developed into the University of

Pennsylvania. He was a prime mover in the establishment of a subscription library,

which he called “the mother of all North American subscription libraries.”

In

the Southern colonies, wealthy planters and merchants imported private tutors

from Ireland or Scotland to teach their children. Some sent their children to

school in England. Having these other opportunities, the upper classes in the

Tidewater were not interested in supporting public education. In addition, the

diffusion of farms and plantations made the formation of community schools

difficult. There were only a few free schools in Virginia.

The

desire for learning did not stop at the borders of established communities,

however. On the frontier, the Scots-Irish, though living in primitive

cabins, were firm devotees of scholarship, and they made great efforts to

attract learned ministers to their settlements.

Literary

production in the colonies was largely confined to New England. Here attention

concentrated on religious subjects. Sermons were the most common products of

the press. A famous Puritan minister, the Reverend Cotton Mather, wrote some

400 works. His masterpiece, Magnalia Christi Americana, presented the

pageant of New England’s history. The most popular single work of the day was

the Reverend Michael Wigglesworth’s long poem, “The Day of Doom,” which

described the Last Judgment in terrifying terms.

In 1704 Cambridge, Massachusetts, launched the colonies’ first successful newspaper. By 1745 there were 22 newspapers being published in British North America.

In

New York, an important step in establishing the principle of freedom of the

press took place with the case of John Peter Zenger, whose New York Weekly

Journal, begun in 1733, represented the opposition to the government. After

two years of publication, the colonial governor could no longer tolerate

Zenger’s satirical barbs, and had him thrown into prison on a charge of

seditious libel. Zenger continued to edit his paper from jail during his

nine-month trial, which excited intense interest throughout the colonies. Andrew Hamilton, the

prominent lawyer who defended Zenger, argued that the charges printed by Zenger were true

and hence not libelous.The jury returned a verdict of not guilty, and Zenger

went free.

The

increasing prosperity of the towns prompted fears that the devil was luring

society into pursuit of worldly gain and may have contributed to the religious

reaction of the 1730s, known as the Great Awakening. Its two immediate sources

were George Whitefield, a Wesleyan revivalist who arrived from England in

1739, and Jonathan Edwards, who served the Congregational Church in

Northampton, Massachusetts.

Whitefield began a religious revival in Philadelphia and then moved on to New England. He enthralled audiences of up to 20,000 people at a time with histrionic displays, gestures, and emotional oratory. Religious turmoil swept throughout New England and the middle colonies as ministers left established churches to preach the revival.

Whitefield began a religious revival in Philadelphia and then moved on to New England. He enthralled audiences of up to 20,000 people at a time with histrionic displays, gestures, and emotional oratory. Religious turmoil swept throughout New England and the middle colonies as ministers left established churches to preach the revival.

Edwards

was the most prominent of those influenced by Whitefield and the Great

Awakening. His most memorable contribution was his 1741 sermon, “Sinners in the

Hands of an Angry God.” Rejecting theatrics, he delivered his message in a

quiet, thoughtful manner, arguing that the established churches sought to

deprive Christianity of its function of redemption from sin. His magnum opus, Of

Freedom of Will (1754), attempted to reconcile Calvinism with the

Enlightenment.

The

Great Awakening gave rise to evangelical denominations (those churches that believe in

personal conversion and the inerrancy of the Bible) and the spirit of

revivalism, which continue to play significant roles in American religious and

cultural life. It weakened the status of the established clergy and provoked

believers to rely on their own conscience. Perhaps most important, it led to the

proliferation of sects and denominations, which in turn encouraged general

acceptance of the principle of religious toleration.

EMERGENCE OF COLONIAL GOVERNMENT - in

the early phases of colonial development, a striking feature was the lack of

controlling influence by the English government. All colonies except Georgia emerged as

companies of shareholders, or as feudal proprietorships stemming from charters

granted by the Crown. The

fact that the king had transferred his immediate sovereignty over the New

World settlements to stock companies and proprietors did not, of course, mean

that the colonists in America were necessarily free of outside control. Under

the terms of the Virginia Company charter, for example, full governmental

authority was vested in the company itself. Nevertheless, the crown expected

that the company would be resident in England. Inhabitants of Virginia, then,

would have no more voice in their government than if the king himself had

retained absolute rule. Still,

the colonies considered themselves chiefly as commonwealths or states, much

like England itself, having only a loose association with the authorities in

London. In

one way or another, exclusive rule from the outside withered away. The colonists

— inheritors of the long English tradition of the struggle for political

liberty — incorporated concepts of freedom into Virginia’s first charter. It

provided that English colonists were to exercise all liberties, franchises,

and immunities “as if they had been abiding and born within this our Realm of

England.” They were, then, to enjoy the benefits of the Magna Carta — the

charter of English political and civil liberties granted by King John in 1215

— and the common law — the English system of law based on legal precedents or

tradition, not statutory law. In 1618 the Virginia Company issued instructions

to its appointed governor providing that free inhabitants of the plantations

should elect representatives to join with the governor and an appointive

council in passing ordinances for the welfare of the colony.

These

measures proved to be some of the most far-reaching in the entire colonial

period. From then on, it was generally accepted that the colonists had a right

to participate in their own government. In most instances, the king, in making

future grants, provided in the charter that the free men of the colony should

have a voice in legislation affecting them. Thus, charters awarded to the Calverts in Maryland,

William Penn in Pennsylvania, the proprietors in North and South Carolina, and

the proprietors in New Jersey specified that legislation should be enacted with

“the consent of the freemen.”

In

New England, for many years, there was even more complete self-government than

in the other colonies. Aboard the Mayflower, the Pilgrims adopted an

instrument for government called the “Mayflower Compact,” to “combine ourselves

together into a civil body politic for our better ordering and preservation

...and by virtue hereof [to] enact, constitute, and frame such just and equal

laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions, and offices ...as shall be thought most

meet and convenient for the general good of the colony....”

Although

there was no legal basis for the Pilgrims to establish a system of

self-government, the action was not contested, and, under the compact, the

Plymouth settlers were able for many years to conduct their own affairs without

outside interference.

A

similar situation developed in the Massachusetts Bay Company, which had been

given the right to govern itself. Thus, full authority rested in the hands of

persons residing in the colony. At first, the dozen or so original members of

the company who had come to America attempted to rule autocratically. But the

other colonists soon demanded a voice in public affairs and indicated that

refusal would lead to a mass migration.

The

company members yield ed,

and control of the government passed to elected representatives. Subsequently,

other New England colonies — such as Connecticut and Rhode Island — also

succeeded in becoming self-governing simply by asserting that they were beyond

any governmental authority, and then setting up their own political system

modeled after that of the Pilgrims at Plymouth.

In

only two cases was the self-government provision omitted. These were New York,

which was granted to Charles II’s brother, the Duke of York (later to become

King James II), and Georgia, which was granted to a group of “trustees.” In

both instances the provisions for governance were short-lived, for the

colonists demanded legislative representation so insistently that the authorities

soon yielded.

In

the mid-17th century, the English were too distracted by their Civil War (1642-49)

and Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan Commonwealth to pursue an effective colonial

policy. After the restoration of Charles II and the Stuart dynasty in 1660,

England had more opportunity to attend to colonial administration. Even then,

however, it was inefficient and lacked a coherent plan. The colonies were left

largely to their own devices.

The

remoteness afforded by a vast ocean also made control of the colonies

difficult. Added to this was the character of life itself in early America. From

countries limited in space and dotted with populous towns, the settlers had come to a

land of seemingly unending reach. On such a continent, natural conditions promoted

a tough individualism, as people became used to making their own

decisions. Government penetrated the backcountry only slowly, and conditions of

anarchy often prevailed on the frontier.

Yet

the assumption of self-government in the colonies did not go entirely

unchallenged. In the 1670s, the Lords of Trade and Plantations, a royal

committee established to enforce the mercantile system in the colonies, moved

to annul the Massachusetts Bay charter because the colony was resisting the

government’s economic policy. James II in 1685 approved a proposal to create a

Dominion of New England and place colonies south through New Jersey under its

jurisdiction, thereby tightening the Crown’s control over the whole region. A

royal governor, Sir Edmund Andros, levied taxes by executive order,

implemented a number of other harsh measures, and jailed those who resisted.

When

news of the Glorious Revolution (1688-89), which deposed James II in England,

reached Boston, the population rebelled and imprisoned Andros. Under a new

charter, Massachusetts and Plymouth were united for the first time in 1691 as

the royal colony of Massachusetts Bay. The other New England colonies quickly

reinstalled their previous governments.

The

English Bill of Rights and the Toleration Act of 1689 affirmed freedom of worship for

Christians in the colonies as well as in England and enforced limits on the

Crown. Equally important, John Locke’s Second Treatise on Government (1690),

the Glorious Revolution’s major theoretical justification, set forth a theory

of government based not on divine right but on contract. It contended that the

people, endowed with natural rights of life, liberty, and property, had the

right to rebel when governments violated their rights.

The

legislatures used these rights to check the power of royal governors and to

pass other measures to expand their power and influence. The recurring clashes

between governor and assembly made colonial politics tumultuous and worked increasingly

to awaken the colonists to the divergence between American and English

interests. In many cases, the royal authorities did not understand importance of what the

colonial assemblies were doing and simply neglected them. Nonetheless, the

precedents and principles established in the conflicts between assemblies and

governors eventually became part of the unwritten “constitution” of the

colonies. In this way, the colonial legislatures asserted the right of

self-government.

4. The french and indian war

France and Britain engaged in a succession of wars in Europe and the Caribbean throughout the 18th century. Though Britain secured certain advantages — primarily in the sugar-rich islands of the Caribbean — the struggles were generally indecisive, and France remained in a powerful position in North America. By 1754, France still had a strong relationship with a number of Native American tribes in Canada and along the Great Lakes. It controlled the Mississippi River and, by establishing a line of forts and trading posts, had marked out a great crescent-shaped empire stretching from Quebec to New Orleans. The British remained confined to the narrow belt east of the Appalachian Mountains. Thus the French threatened not only the British Empire but also the American colonists themselves, for in holding the Mississippi Valley, France could limit their westward expansion.

An

armed clash took place in 1754 at Fort Duquesne, the site where Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, is

now located, between a band of French regulars and Virginia militiamen under

the command of 22-year-old George Washington, a Virginia planter and

surveyor. The British government attempted to deal with the conflict by calling

a meeting of representatives from New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and the

New England colonies. From June 19 to July 10, 1754, the Albany Congress, as it

came to be known, met with the Iroquois in Albany, New York, in order to

improve relations with them and secure their loyalty to the British.

But

the delegates also declared a union of the American colonies “absolutely

necessary for their preservation” and adopted a proposal drafted by Benjamin

Franklin. The Albany Plan of Union provided for a president appointed by the

king and a grand council of delegates chosen by the assemblies, with each

colony to be represented in proportion to its financial contributions to the

general treasury. This body would have charge of defense, Native American relations,

and trade and settlement of the west. Most importantly, it would have

independent authority to levy taxes. But none of the colonies accepted the plan,

since they were not prepared to surrender either the power of taxation or

control over the development of the western lands to a central authority.

|

| Battle of Quebec, 13 September 1759 |

England’s

superior strategic position and her competent leadership ultimately brought

victory in the conflict with France, known as the French and Indian War in America

and the Seven Years’ War in Europe. Only a modest portion of it was fought in

the Western Hemisphere.

In

the Peace of Paris (1763), France relinquished all of Canada, the Great Lakes,

and the territory east of the Mississippi to the British. The dream of a French

empire in North America was over.

| |

Having

triumphed over France, Britain was now compelled to face a problem that it had

hitherto neglected, the governance of its empire. London thought it essential

to organize its now vast possessions to facilitate defense, reconcile the divergent

interests of different areas and peoples, and distribute more evenly the cost

of imperial administration.

In

North America alone, British territories had more than doubled. A population

that had been predominantly Protestant and English now included French-speaking

Catholics from Quebec, and large numbers of partly Christianized Native Americans. Defense and administration

of the new territories, as well as of the old, would require huge sums of money

and increased personnel. The old colonial system was obviously inadequate to

these tasks. Measures to establish a new one, however, would rouse the latent

suspicions of colonials who increasingly would see Britain as no longer a

protector of their rights, but rather a danger to them.

An

upper-class, with wealth based on large plantations operated by slave labor,

and holding significant political power and even control over the churches,

emerged in South Carolina and Virginia. A unique class system operated in

upstate New York, where Dutch tenant farmers rented land from very wealthy

Dutch proprietors, such as the Rensselaer family. The other colonies were more

equalitarian, with Pennsylvania being representative. By the mid-18th century

Pennsylvania was basically a middle-class colony with limited deference to its

small upper-class. A writer in the Pennsylvania Journal in

1756 summed it up:

The People of

this Province are generally of the middling Sort, and at present pretty much

upon a Level. They are chiefly industrious Farmers, Artificers or Men in Trade;

they enjoy in are fond of Freedom, and the meanest among them thinks

he has a right to Civility from the greatest.

5. Political integration and autonomy

The French and Indian War (1754–63)

was a watershed event in the political development of the colonies. It was also

part of the larger Seven

Years' War. The influence of the main rivals of the British Crown in the colonies and

Canada, the French and North American Indians, was significantly reduced with

the territory of the Thirteen

Colonies expanding into New

France both in Canada and the Louisiana Territory. Moreover,

the war effort resulted in greater political integration of the colonies, as

reflected in the Albany

Congress and symbolized by Benjamin

Franklin's call for the colonies to "Join or Die". Franklin was a man of

many inventions – one of which was the concept of a United States of

America, which emerged after 1765 and was realized in July 1776.

|

| Join, or Die: This 1756 political cartoon by Benjamin Franklin urged the colonies to join together during the French and Indian War. |

In ensuing years, strains developed in the relations between the colonists and the Crown. The British Parliament passed the Stamp Act of 1765, imposing a tax on the colonies without going through the colonial legislatures. The issue was drawn: did Parliament have this right to tax Americans who were not represented in it? Crying "No taxation without representation", the colonists refused to pay the taxes as tensions escalated in the late 1760s and early 1770s.

The Boston

Tea Party in 1773 was a direct action by activists in the town of Boston to

protest against the new tax on tea. Parliament quickly responded the next year

with the Coercive Acts, stripping Massachusetts of its historic right of

self-government and putting it under army rule, which sparked outrage and

resistance in all thirteen colonies. Patriot leaders from all 13 colonies

convened the First Continental Congress to

coordinate their resistance to the Coercive Acts. The Congress called for

a boycott of British trade, published

a list of rights and grievances, and petitioned the king for

redress of those grievances. The appeal to the Crown had no effect, and so

the Second Continental Congress was

convened in 1775 to organize the defense of the colonies against the British

Army.

Ordinary folk

became insurgents against the British even though they were unfamiliar with the

ideological rationales being offered. They held very strongly a sense of

"rights" that they felt the British were deliberately

violating – rights that stressed local autonomy, fair dealing, and

government by consent. They were highly sensitive to the issue of tyranny,

which they saw manifested in the arrival in Boston of the British Army to

punish the Bostonians. This heightened their sense of violated rights, leading

to rage and demands for revenge. They had faith that God was on their side.

The American

Revolutionary War began at Concord and Lexington in April 1775

when the British tried to seize ammunition supplies and arrest the Patriot

leaders.

In terms of

political values, the Americans were largely united on a concept called Republicanism, that

rejected aristocracy and emphasized civic duty and a fear of corruption. For

the Founding Fathers, according to one team of historians, "republicanism

represented more than a particular form of government. It was a way of life, a

core ideology, an uncompromising commitment to liberty, and a total rejection

of aristocracy."

SIDEBAR: THE WITCHES OF SALEM

In 1692 a group of adolescent girls in

Salem Village, Massachusetts, became subject to strange fits after hearing

tales told by a West Indian slave. When they were questioned, they accused

several women of being witches who were tormenting them. The towns people were

appalled but not surprised: belief in witchcraft was widespread throughout

17th-century America and Europe.

What happened next - although an

isolated event in American history - provides a vivid window into the social

and psychological world of Puritan New England. Town officials convened a court

to hear the charges of witchcraft, and swiftly convicted and executed a

tavern keeper, Bridget Bishop. Within a month, five other women had been

convicted and hanged.

Nevertheless, the hysteria grew, in

large measure because the court permitted witnesses to testify that they had

seen the accused as spirits or in visions. By its very nature, such

"spectral evidence" was especially dangerous, because it could be

neither verified nor subject to objective examination. By the fall of 1692,

more than 20 victims, including several men, had been executed, and more than

100 others were in jail -- among them some of the town's most prominent

citizens. But now the hysteria threatened to spread beyond Salem, and ministers

throughout the colony called for an end to the trials. The governor of the

colony agreed and dismissed the court. Those still in jail were later acquitted

or given reprieves.

|

| Examination of a Witch |

The Salem witch trials have long

fascinated Americans. On a psychological level, most historians agree that

Salem Village in 1692 was seized by a kind of public hysteria, fueled by a

genuine belief in the existence of witchcraft. They point out that, while some