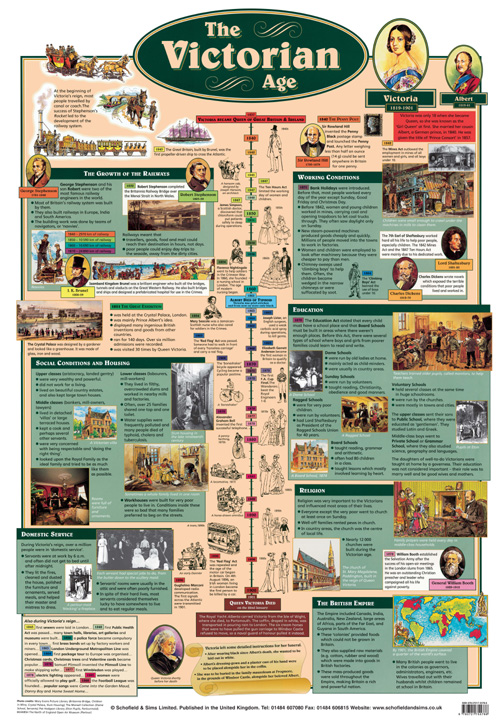

the Victorian era of British history was the

period of Queen Victoria's reign from

20 June 1837 until her death, on 22 January 1901. It was a long period of

peace, prosperity, refined sensibilities and national self-confidence for

Britain. Some

scholars date the beginning of the period in terms of sensibilities and

political concerns to the passage of the Reform Act 1832.

Queen Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22

January 1901) was Queen of the United

Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until

her death. From 1 May 1876, she had the additional title of Empress of India.

Victoria was

the daughter of Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and

Strathearn, the fourth son of King George III. Both the

Duke of Kent and King George III died in 1820, and Victoria was raised under

close supervision by her German-born mother Princess Victoria of

Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. She inherited the throne aged 18, after her

father's three elder brothers had all died, leaving no surviving legitimate

children. The United Kingdom was already an established constitutional monarchy, in which the sovereign held

relatively little direct political power. Privately, Victoria attempted to

influence government policy and ministerial appointments; publicly, she became

a national icon who was identified with strict standards of personal morality.

Victoria

married her first cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, in 1840. Their nine children married

into royal and noble families across the continent, tying them together and

earning her the sobriquet "the grandmother of Europe". After Albert's

death in 1861, Victoria plunged into deep mourning and avoided public

appearances. As a result of her seclusion, republicanism temporarily

gained strength, but in the latter half of her reign her popularity recovered.

Her Golden and Diamond

Jubilees were times of public celebration.

|

| Portrait by Winterhalter, 1859 |

Her reign of 63

years and seven months is known as the Victorian era.

It was a period of industrial, cultural, political, scientific, and military

change within the United Kingdom, and was marked by a great expansion of the British Empire.

She was the last British monarch of the House of Hanover.

Her son and successor, Edward

VII, belonged to the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the line of his father.

Culturally

there was a transition away from the rationalism of the

Georgian period and toward romanticism and mysticism

with regard to religion, social values, and arts. In international relations the era was a long period of peace, known

as the Pax

Britannica, and economic, colonial, and industrial

consolidation, temporarily disrupted by the Crimean War in 1854.

The end of the period saw the Boer War.

Domestically, the agenda was increasingly liberal with a number of shifts in

the direction of gradual political reform, industrial

reform and the widening of the voting franchise.

Two especially

important figures in this period of British history are the prime

ministers Benjamin

Disraeli and William Gladstone, whose

contrasting views changed the course of history. Disraeli, favoured by the

queen, was a gregarious Tory. His rival Gladstone, a Liberal distrusted by the

Queen, served more terms and oversaw much of the overall legislative

development of the era.

The population

of England and Wales almost doubled from 16.8 million in 1851 to 30.5

million in 1901. Scotland's

population also rose rapidly, from 2.8 million in 1851 to 4.4 million in 1901.

Ireland's population however decreased sharply, from 8.2 million in 1841 to

less than 4.5 million in 1901, mostly due to the Great

Famine. At the

same time, around 15 million emigrants left the

United Kingdom in the Victorian era, settling mostly in the United States,

Canada, New Zealand and Australia.

During the

early part of the era, the House

of Commons was headed by the two parties, the Whigs and the Conservatives. From the

late 1850s onwards, the Whigs became the Liberals. These

parties were led by many prominent statesmen including Lord Melbourne, Sir Robert Peel, Lord

Derby, Lord Palmerston, William Gladstone, Benjamin Disraeli,

and Lord

Salisbury. The unsolved problems relating to Irish

Home Rule played a great part in politics in the later Victorian era, particularly in

view of Gladstone's determination to achieve a political settlement.

Leadership - prime Ministers of the period included: Lord Melbourne, Sir Robert Peel, Lord John Russell, Lord Derby, Lord Aberdeen, Lord Palmerston, Benjamin Disraeli, William Ewart Gladstone, Lord Salisbury, and Lord Rosebery.

Disraeli

|

| Disraeli |

Benjamin Disraeli (1804–1881), prime minister 1868 and 1874–80, remains an iconic hero of the Conservative Party. He played a central role in the creation the Party, defining its policies and its broad outreach. Disraeli is remembered for his influential voice in world affairs, his political battles with the Liberal leader William Gladstone, and his one-nation conservatism or "Tory democracy". He made the Conservatives the party most identified with the glory and power of the British Empire. He was born into a Jewish family, which became Episcopalian when he was 12 years old.

Disraeli fought to protect established political, social, and religious values and elites; he emphasized the need for national leadership in response to radicalism, uncertainty, and materialism. He is especially known for his enthusiastic support for expanding and strengthening the British Empire in India and Africa as the foundation of British greatness, in contrast to Gladstone's negative attitude toward imperialism. Gladstone denounced Disraeli's policies of territorial aggrandizement, military pomp, and imperial symbolism (such as making the Queen Empress of India), saying it did not fit a modern commercial and Christian nation.

In foreign policy he is best known for battling and besting Russia. Disraeli's second term was dominated by the Eastern Question—the slow decay of the Ottoman Empire and the desire of Russia, to gain at its expense. Disraeli arranged for the British to purchase a major interest in the Suez Canal Company (in Ottoman-controlled Egypt). In 1878, faced with Russian victories against the Ottomans, he worked at the Congress of Berlin to maintain peace in the Balkans and made terms favourable to Britain which weakened Russia, its longstanding enemy.

Disraeli's old reputation as the "Tory democrat" and promoter of the welfare state has faded as historians argue that he had few proposals for social legislation in 1874–80, and that the 1867 Reform Act did not reflect a vision for the unenfranchised working man. However he did work to reduce class antagonism, for as Perry notes, "When confronted with specific problems, he sought to reduce tension between town and country, landlords and farmers, capital and labour, and warring religious sects in Britain and Ireland—in other words, to create a unifying synthesis."

Gladstone

|

| Gladstone |

Gladstone's financial policies, based on the notion of balanced budgets, low taxes and laissez-faire, were suited to a developing capitalist society but could not respond effectively as economic and social conditions changed. Called the "Grand Old Man" later in life, he was always a dynamic popular orator who appealed strongly to British workers and lower middle class. The deeply religious Gladstone brought a new moral tone to politics with his evangelical sensibility and opposition to aristocracy. His moralism often angered his upper-class opponents (including Queen Victoria, who strongly favoured Disraeli), and his heavy-handed control split the Liberal party. His foreign policy goal was to create a European order based on cooperation rather than conflict and mutual trust instead of rivalry and suspicion; the rule of law was to supplant the reign of force and self-interest. This Gladstonian concept of a harmonious Concert of Europe was opposed to and ultimately defeated by the Germans with a Bismarckian system of manipulated alliances and antagonisms

2. Economic progress in the Victorian Age

A. Introduction of the

economic development - prior to the

Industrial Revolution most of the workforce was employed in agriculture, either

as self-employed farmers as land owners or tenants, or as landless agricultural

laborers. By the time of the Industrial Revolution the putting-out system whereby

farmers and townspeople produced goods in their homes, often described as cottage

industry, was the standard. Typical putting out system goods included

spinning and weaving. Merchant capitalist provided the raw materials, typically

paid workers by the piece, and were

responsible for the sale of the goods. Embezzlement of supplies by workers and

poor quality were common problems. The logistical effort in procuring and

distributing raw materials and picking up finished goods were also limitations

of the putting out system.

Some early spinning

and weaving machinery, such as a 40

spindle jenny for about 6 pounds in 1792, was affordable for

cottagers. Later

machinery such as spinning frames, spinning

mules and power looms were expensive (especially if water powered), giving

rise to capitalist ownership of factories. Many workers, who had nothing but

their labor to sell, became factory workers out of necessity. The change in the social relationship of the factory worker compared to

farmers and cottagers was viewed unfavorably by Karl

Marx, however, he recognized the increase in productivity made possible by

technology.

B. Free trade - after 1840 Britain abandoned mercantilism and committed its economy to free

trade, with few barriers or

tariffs. This was most evident in the repeal in 1846 of the Corn

Laws, which had imposed

stiff tariffs on imported grain. The end of these laws opened the British

market to unfettered competition, grain prices fell, and food became more

plentiful.

|

| The Great Exhibition in London in 1851. The United Kingdom was the first country in the world to industrialise. |

From 1815 to 1870 Britain reaped the

benefits of being the world's first modern, industrialised nation. It described

itself as 'the workshop of the world', meaning that its finished goods were

produced so efficiently and cheaply that they could often undersell comparable,

locally manufactured goods in almost any other market. If political conditions in a

particular overseas market were stable enough, Britain could dominate its

economy through free trade alone without having to resort to formal rule or

mercantilism. Britain was even supplying half the needs in manufactured goods of

such nations as Germany, France, Belgium, and the United States. By 1820, 30% of

Britain's exports went to its

Empire, rising slowly to 35%

by 1910. Apart from coal and iron, most raw materials had to be imported so

that, in the 1830s, the main imports were (in order): raw cotton (from the

American South), sugar (from the West Indies), wool, silk, tea (from China),

timber (from Canada), wine, flax, hides and tallow. By 1900, Britain's global share

soared to 22.8% of total imports. By 1922, its global share soared to 14.9% of

total exports and 28.8% of manufactured exports.

Railways - the British invented the modern railway

system and exported it to the world. They emerged from Britain's elaborate

system of canals and roadways, which both used horses to haul coal for the new

steam engines installed in textile factories. Britain furthermore had the

engineers and entrepreneurs needed to create and finance a railway system. In

1815, George Stephenson invented the modern steam

locomotive, launching a technological race bigger, more powerful locomotives

using higher and higher steam pressures. Stephenson's key innovation came when

he integrated all the components of a railways system in 1825

by opening the Stockton and Darlington line. It demonstrated it was commercially

feasible to have a system of usable length. London poured money into railway

building—a veritable bubble, but one with permanent value. Thomas

Brassey brought British

railway engineering to the world, with construction crews that in the 1840s

employed 75,000 men across Europe. Every nation copied the British model.

Brassey expanded throughout the British Empire and Latin America. His companies

invented and improved thousands of mechanical devices, and developed the

science of civil engineering to build roadways, tunnels and bridges. The

telegraph, although invented and developed separately, proved essential for the

internal communications of the railways because it allowed slower trains to

pull over as express trains raced through. Telegraphs made it possible to use a

single track for two-way traffic, and to locate where repairs were needed.

Britain had a superior financial system based in London that funded both the

railways in Britain and also in many other parts of the world, including the

United States, up until 1914. The boom years were 1836 and 1845–47, when

Parliament authorized 8,000 miles of railways with a projected future total of

£200 million; that about equalled one year of Britain's GDP. Once a charter was

obtained, there was little government regulation, as laissez faire and private

ownership had become accepted practices.

|

| Euston station in London |

By 1850 Britain had a well integrated,

well engineered system that provided fast, on-time, inexpensive movement of

freight and people to every city and most rural districts. Freight rates had

plunged to a penny a ton mile for coal. The system directly or indirectly employed

tens of thousands of engineers, conductors, mechanics, repairmen, accountants,

station agents and managers, bringing a new level of business sophistication

that could be applied to many other industries, and helping many small and

large businesses to expand their role in the industrial revolution. Thus

railways had a tremendous impact on industrialization. By lowering

transportation costs, they reduced costs for all industries moving supplies and

finished goods, and they increased demand for the production of all the inputs

needed for the railway system itself. The system kept growing; by 1880, there

were 13,500 locomotives which each carried 97,800 passengers a year, or 31,500

tons of freight.

Second Industrial Revolution - during the First Industrial Revolution,

the industrialist replaced the merchant as the dominant figure in the

capitalist system. In the later decades of the 19th century, when the ultimate

control and direction of large industry came into the hands of financiers, industrial

capitalism gave way to financial capitalism and the corporation. The

establishment of behemoth industrial empires, whose assets were controlled and

managed by men divorced from production, was a dominant feature of this third

phase.

|

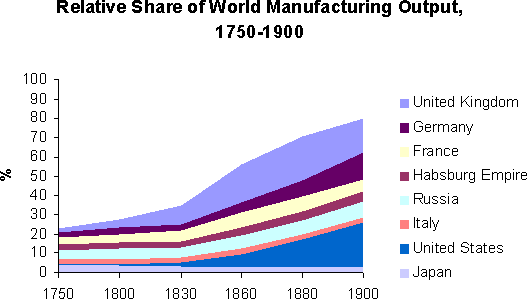

As the Industrial Revolution developed British manufactured output surged ahead of other economies. After the Industrial Revolution, it was overtaken later by the United States.

|

Amalgamation of industrial cartels into larger corporations, mergers

and alliances of separate firms, and technological advancement (particularly

the increased use of electric power and internal combustion engines fuelled by gasoline) were mixed blessings

for British business during the late Victorian

era. The ensuing

development of more intricate and efficient machines along with mass production

techniques greatly expanded output and lowered production costs. As a result, production

often exceeded domestic demand. Among the new conditions, more markedly evident

in Britain, the forerunner of Europe's industrial states, were the long-term

effects of the severe Long

Depression of 1873-1896,

which had followed fifteen years of great economic instability. Businesses in

practically every industry suffered from lengthy periods of low — and falling —

profit rates and price deflation after 1873.

Long-term economic trends led Britain, and

to a lesser extent, other industrialising nations such as the United States and

Germany, to be more receptive to the desires of prospective overseas

investment. Through their investments in industry, banks were able to exert a

great deal of control over the British economy and politics. Cut-throat

competition in the mid-19th century caused the creation of super corporations

and conglomerates.

By the 1870s, financial houses in London

had achieved an unprecedented level of control over industry. This contributed

to increasing concerns among policymakers over the protection of British

investments overseas — particularly those in the securities of foreign

governments and in foreign-government-backed development activities, such as

railways. Although it had been official British policy to support such

investments, with the large expansion of these investments in the 1860s, and

the economic and political instability of many areas of investment (such

as Egypt), calls upon the government for

methodical protection became increasingly pronounced in the years leading up to

the Crystal Palace Speech. At the end of the Victorian

era, the service

sector (banking,

insurance and shipping, for example) began to gain prominence at the expense of

manufacturing.

Foreign trade - foreign trade tripled in

volume between 1870 and 1914; most of the activity occurred with other

industrialised countries. Britain ranked as the world's largest trading nation

in 1860, but by 1913 it had lost ground to both the United States and Germany:

British and German exports in that year each totaled $2.3 billion, and those of

the United States exceeded $2.4 billion. As foreign trade increased, so in

proportion did the amount of it going outside the Continent. In 1840, £7.7

million of its export and £9.2 million of its import trade was done outside

Europe; in 1880 the figures were £38.4 million and £73 million. Europe's

economic contacts with the wider world were multiplying, much as Britain's had

been doing for years. In many cases, colonial control followed private

investment, particularly in raw materials and agriculture. Intercontinental

trade between North and South constituted a higher proportion of global trade

in this era than in the late 20th century period of globalisation.

Export of capital - London strengthened its

position as the world's financial capital, the export of capital was a major

base of the British economy 1880 to 1913, the "golden era" of

international finance.

Investment was especially heavy in the

independent nations of Latin America, which were eager for infrastructure

improvements such as railways built by the British, ports, and telegraph and

telephone systems. British merchants dominated trade in the region. Not all the

investments paid off; the mines in the Sudan, for example, lost money. By 1913 Britain's

overseas assets totaled about four billion pounds.

Business practices - Britain persisted in its

free trade policy even as its major rivals, the U.S. and Germany, turned to

high tariffs (as did Canada). American heavy industry grew faster than Britain,

and by the 1890s was crowding British machinery and other products out of the

world market.

New business practices in the areas of

management and accounting made possible the more efficient operation of large

companies. For example, in steel, coal, and iron companies 19th-century

accountants utilized sophisticated, fully integrated accounting systems to

calculate output, yields, and costs to satisfy management information

requirements. South Durham Steel and Iron, was a large horizontally

integrated company that operated mines, mills, and shipyards. Its management

used traditional accounting methods with the goal of minimizing production

costs, and thus raising its profitability. By contrast one of its competitors,

Cargo Fleet Iron introduced mass production milling techniques through the

construction of modern plants. Cargo Fleet set high production goals and

developed an innovative but complicated accounting system to measure and report

all costs throughout the production process. However, problems in obtaining

coal supplies and the failure to meet the firm's production goals forced Cargo

Fleet to drop its aggressive system and return to the sort of approach South

Durham Steel was using.

The American "invasion" of the

British home market demanded a response. Tariffs, although increasingly under

consideration, were not imposed until the 1930s. Therefore, British businessmen

were obliged to lose their market or else rethink and modernize their

operations. The boot and shoe industry faced increasing imports of American

footwear; Americans took over the market for shoe machinery. British companies

realized they had to meet the competition so they reexamine their traditional

methods of work, labor utilization, and industrial relations, and to rethink

how to market footwear in terms of the demand for fashion.

Standards

of living - the effects on living conditions

the industrial revolution have been very controversial, and were hotly debated

by economic and social historians from the 1950s to the 1980s. A series of 1950s essays by Henry

Phelps Brown and Sheila V. Hopkins later set the academic

consensus that the bulk of the population, that was at the bottom of the social

ladder, suffered severe reductions in their living standards. During 1813–1913, there was a significant

increase in worker wages.

Food

and nutrition - chronic hunger

and malnutrition were the norm for the majority of the population of the world

including Britain and France, until the late 19th century. Until about 1750, in

large part due to malnutrition, life expectancy in France was about 35 years,

and only slightly higher in Britain. The US population of the time was

adequately fed, much taller on average and had life expectancy of 45–50 years.

In Britain and

the Netherlands, food supply had been increasing and prices falling before the

Industrial Revolution due to better agricultural practices; however, population

grew too, as noted by Thomas

Malthus. Before

the Industrial Revolution, advances in agriculture or technology soon led to an

increase in population, which again strained food and other resources, limiting

increases in per capita income. This condition is called the Malthusian trap, and it was

finally overcome by industrialisation.

Transportation

improvements, such as canals and improved roads, also lowered food costs.

Railroads were introduced near the end of the Industrial Revolution.

The Billingsgate Fish Market in

the early 19th century

3. Social conflict and its resolution in the Victorian Age

A. Housing - living

conditions during the Industrial Revolution varied from splendour for factory

owners to squalor for workers. In The

Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 Friedrich

Engels described backstreet sections of Manchester and other

mill towns, where people lived in crude shanties and shacks, some not

completely enclosed, some with dirt floors. These shantytowns had narrow

walkways between irregularly shaped lots and dwellings. There were no sanitary

facilities. Population density was extremely high. Eight to ten unrelated mill

workers often shared a room, often with no furniture, and slept on a pile of

straw or sawdust. Toilet

facilities were shared if they existed. Disease spread through a contaminated

water supply. Also, people were at risk of developing pathologies due to

persistent dampness.

|

| Over London by Rail Gustave Doré c. 1870. Shows the densely populated and polluted environments created in the new industrial cities. |

The famines

that troubled rural areas did not happen in industrial areas. But urban

people—especially small children—died due to diseases spreading through the

cramped living conditions. Tuberculosis (spread

in congested dwellings), lung diseases from the mines, cholera from

polluted water and typhoid were also common.

Not everyone

lived in such poor conditions. The Industrial Revolution also created a middle

class of professionals, such as lawyers and doctors, who lived in much better conditions.

Conditions

improved over the course of the 19th century due to new public health acts

regulating things such as sewage, hygiene and home construction. In the

introduction of his 1892 edition, Engels notes that most of the conditions he

wrote about in 1844 had been greatly improved.

B. Clothing

and consumer goods - consumers

benefited from falling prices for clothing and household articles such as cast

iron cooking utensils, and in the following decades, stoves for cooking and

space heating.

C. Population

increase - according to Robert Hughes

in The Fatal Shore, the population of England and

Wales, which had remained steady at 6 million from 1700 to 1740, rose dramatically

after 1740. The population of England had more than doubled from 8.3 million in

1801 to 16.8 million in 1850 and, by 1901, had nearly doubled again to 30.5

million. Improved

conditions led to the population of Britain increasing from 10 million to 40 million

in the 1800s. Europe's

population increased from about 100 million in 1700 to 400 million by 1900.

The Industrial

Revolution was the first period in history during which there was a

simultaneous increase in population and in per capita income.

D. Social

structure and working conditions - in terms of social structure, the Industrial Revolution witnessed the

triumph of a middle class of industrialists and businessmen over a landed

class of nobility and gentry. Ordinary working people found increased

opportunities for employment in the new mills and factories, but these were

often under strict working conditions with long hours of labour dominated by a

pace set by machines. As late as the year 1900, most industrial workers in the

United States still worked a 10-hour day (12 hours in the steel industry), yet

earned from 20% to 40% less than the minimum deemed necessary for a decent life. However, harsh working conditions were prevalent long

before the Industrial Revolution took place. Pre-industrial society was very

static and often cruel—child labour, dirty living conditions, and long working hours were

just as prevalent before the Industrial Revolution.

E. Industrialisation - led to the

creation of the factory. Arguably the first highly mechanised was John

Lombe's water-powered

silk mill at Derby, operational by 1721. Lombe learned silk thread

manufacturing by taking a job in Italy and acting as an industrial spy;

however, since the silk industry there was a closely guarded secret, the state

of the industry there is unknown. Because Lombe's factory was not successful

and there was no follow through, the rise of the modern factory dates to

somewhat later when cotton spinning was mechanised.

The factory

system contributed to the growth of urban areas, as large numbers of workers

migrated into the cities in search of work in the factories. Nowhere was this

better illustrated than the mills and associated industries of Manchester,

nicknamed "Cottonopolis", and the world's first industrial city. Manchester experienced a six-times increase in

its population between 1771 and 1831. Bradford grew by 50% every ten years

between 1811 and 1851 and by 1851 only 50% of the population of Bradford was

actually born there.

|

| Manchester ("Cottonopolis"), pictured in 1840, showing the mass of factory chimneys |

For much of

the 19th century, production was done in small mills, which were

typically water-powered and

built to serve local needs. Later, each factory would have its own steam engine

and a chimney to give an efficient draft through its boiler.

The transition

to industrialisation was not without difficulty. For example, a group of

English workers known as Luddites formed

to protest against industrialisation and sometimes sabotaged factories.

In other

industries the transition to factory production was not so divisive. Some

industrialists themselves tried to improve factory and living conditions for

their workers. One of the earliest such reformers was Robert

Owen, known for his pioneering efforts in improving conditions for workers at

the New Lanark mills, and often regarded as one of

the key thinkers of the early

socialist movement.

Child

labour - the Industrial Revolution led to a population increase but the chances of

surviving childhood did not improve throughout the Industrial Revolution,

although infant mortality rates were reduced markedly. There was still limited opportunity for education and

children were expected to work. Employers could pay a child less than an adult

even though their productivity was comparable; there was no need for strength

to operate an industrial machine, and since the industrial system was

completely new, there were no experienced adult labourers. This made child

labour the labour of choice for manufacturing in the early phases of the

Industrial Revolution between the 18th and 19th centuries. In England and

Scotland in 1788, two-thirds of the workers in 143 water-powered cotton

mills were described as children.

Child

labour existed before the Industrial Revolution but with the increase in

population and education it became more visible. Many children were forced to

work in relatively bad conditions for much lower pay than their elders, 10–20% of an adult male's wage. Children as young as four were employed. Beatings and long hours were common, with some

child coal miners and hurriers working

from 4 am until 5 pm. Conditions

were dangerous, with some children killed when they dozed off and fell into the

path of the carts, while others died from gas explosions. Many children developed lung

cancer and other diseases and died before the age of 25. Workhouses would

sell orphans and abandoned children as "pauper apprentices", working

without wages for board and lodging. Those who ran

away would be whipped and returned to their masters, with some masters shackling them to

prevent escape. Children

employed as mule scavengers by cotton

mills would crawl under machinery to pick up cotton, working 14 hours a

day, six days a week. Some lost hands or limbs, others were crushed under the

machines, and some were decapitated. Young girls

worked at match factories, where phosphorus fumes would cause many to

develop phossy jaw. Children employed at glassworks were

regularly burned and blinded, and those working at potteries were

vulnerable to poisonous clay dust.

Reports were

written detailing some of the abuses, particularly in the coal mines and textile factories, and these helped to popularise the children's plight. The public

outcry, especially among the upper and middle classes, helped stir change in

the young workers' welfare.

Politicians

and the government tried to limit child labour by law but factory owners

resisted; some felt that they were aiding the poor by giving their children

money to buy food to avoid starvation, and others

simply welcomed the cheap labour. In 1833 and 1844, the first general laws

against child labour, the Factory

Acts, were passed in Britain: Children younger than nine were not allowed to

work, children were not permitted to work at night, and the work day of youth

under the age of 18 was limited to twelve hours. Factory inspectors supervised

the execution of the law, however, their scarcity made enforcement difficult. About ten years later, the employment of

children and women in mining was forbidden. These laws decreased the number of

child labourers, however child labour remained in Europe and the United States

up to the 20th century.

Luddites - the rapid industrialisation of the English economy cost

many craft workers their jobs. The movement started first with lace and hosiery workers near Nottingham and spread to other areas of the textile

industry owing to early industrialisation. Many weavers also found themselves

suddenly unemployed since they could no longer compete with machines which only

required relatively limited (and unskilled) labour to produce more cloth than a

single weaver. Many such unemployed workers, weavers and others, turned their animosity

towards the machines that had taken their jobs and began destroying factories

and machinery. These attackers became known as Luddites, supposedly followers

of Ned

Ludd, a folklore figure. The first attacks of the Luddite movement began in

1811. The Luddites rapidly gained popularity, and the British government took

drastic measures, using the militia or army to

protect industry. Those rioters who were caught were tried and hanged, or transported for

life.

Unrest

continued in other sectors as they industrialised, such as with agricultural

labourers in the 1830s when large parts of southern Britain were affected by

the Captain Swing disturbances. Threshing machines were a

particular target, and hayrick burning was a popular activity. However, the

riots led to the first formation of trade

unions, and further pressure for reform.

Organisation

of labour - the Industrial Revolution

concentrated labour into mills, factories and mines, thus facilitating the

organisation ofcombinations or trade

unions to help advance the interests of working people. The power of a union

could demand better terms by withdrawing all labour and causing a consequent

cessation of production. Employers had to decide between giving in to the union

demands at a cost to themselves or suffering the cost of the lost production.

Skilled workers were hard to replace, and these were the first groups to

successfully advance their conditions through this kind of bargaining.

The main

method the unions used to effect change was strike

action. Many strikes were painful events for both sides, the unions and the

management. In Britain, the Combination Act 1799 forbade

workers to form any kind of trade union until its repeal in 1824. Even after

this, unions were still severely restricted.

In 1832,

the Reform Act extended

the vote in Britain but did not grant universal suffrage. That year six men

from Tolpuddle in

Dorset founded the Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers to protest

against the gradual lowering of wages in the 1830s. They refused to work for

less than ten shillings a week, although by this time wages had been reduced to

seven shillings a week and were due to be further reduced to six. In 1834 James

Frampton, a local landowner, wrote to the Prime Minister, Lord

Melbourne, to complain about the union, invoking an obscure law from 1797 prohibiting

people from swearing oaths to each other, which the members of the Friendly

Society had done. James Brine, James Hammett, George Loveless, George's brother

James Loveless, George's brother in-law Thomas Standfield, and Thomas's son

John Standfield were arrested, found guilty, and transported to Australia. They

became known as the Tolpuddle

Martyrs. In the 1830s and 1840s, the Chartist movement was the first large-scale organised working class political

movement which campaigned for political equality and social justice. Its Charter of

reforms received over three million signatures but was rejected by Parliament

without consideration.

Eventually,

effective political organisation for working people was achieved through the

trades unions who, after the extensions of the franchise in 1867 and 1885,

began to support socialist political parties that later merged to became the

British Labour Party.

Other

effects - during the

Industrial Revolution, the life

expectancy of children increased dramatically. The percentage of the children

born in London who died before the age of five decreased from 74.5% in 1730–1749

to 31.8% in 1810–1829. The growth of

modern industry since the late 18th century led to massive urbanisation and the

rise of new great cities, first in Europe and then in other regions, as new

opportunities brought huge numbers of migrants from rural communities into urban

areas.

In 1800, only 3% of the world's population lived in cities, compared to nearly 50% today (the beginning of

the 21st century). Manchester

had a population of 10,000 in 1717, but by 1911 it had burgeoned to 2.3

million.

Chester, c. 1880

4. Imperial expansion in the Victorian Age

A. Pax Britannica (Latin

for "British Peace", modelled after Pax

Romana) was the period

of relative peace in Europe and the world (1815–1914) during

which the British

Empire became the global hegemonic power

and adopted the role of a global police force.

Between 1815

and 1914, a period referred to as Britain's "imperial

century," around 10,000,000 square miles (26,000,000 km2) of territory and roughly 400 million people were

added to the British Empire. Victory

over Napoleonic

France left the British without any serious international rival, other than

perhaps Russia

in central Asia. When

Russia acted aggressively in the 1850s, the British and French defeated it in

the Crimean War (1854–56),

thereby protecting the by-then feeble Ottoman Empire.

Britain's

Royal Navy controlled most of the key maritime trade routes and enjoyed unchallenged sea power. Alongside

the formal control it exerted over its own colonies, Britain's dominant

position in world trade meant that it effectively controlled access to many

regions, such as Asia and Latin

America. British merchants, shippers and bankers had such an overwhelming

advantage over everyone else that in addition to its colonies it had an "informal empire".

B. History - after losing the American colonies in the American Revolution, Britain turned

towards Asia, the Pacific and later Africa with subsequent exploration leading

to the rise of the Second British Empire (1783–1815).

The industrial revolution began in

Great Britain in the late 1700s and new ideas emerged about free markets, such

as Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations (1776).

Free trade became a central principle that Britain practiced by the 1840s. It

played a key role in Britain's economic

growth and financial dominance.

From the end

of the Napoleonic

Wars in 1815 until World

War I in 1914, the United Kingdom played the role of global hegemon (most

powerful actor). Imposition of a "British Peace" on key maritime

trade routes began in 1815 with the annexation of British Ceylon (now Sri

Lanka). Under

the British Residency of the Persian Gulf, local Arab

rulers agreed to a number of treaties that formalised Britain’s protection of

the region. Britain imposed an anti-piracy treaty, known as the General Treaty

of 1820, on all Arab rulers in the region. By signing the Perpetual Maritime

Truce of 1853, Arab rulers gave up their right to wage war at sea in return for

British protection against external threats. The global superiority of British military and

commerce was aided by a divided and relatively weak continental Europe, and the

presence of the Royal Navy on all of the world's oceans and seas. Even

outside its formal empire, Britain controlled trade with many countries such as

China, Siam, and Argentina. Following the Congress of Vienna the

British Empire's economic strength continued to develop through naval dominance and diplomatic efforts to maintain a balance of power in

continental Europe.

In this era,

the Royal Navy provided services around the world that benefited other nations,

such as the suppression

of piracy and blocking the slave trade. The Slave Trade Act 1807 had

banned the trade across the British Empire, after which the Royal Navy

established the West Africa Squadron and the

government negotiated international treaties under

which they could enforce the ban. Sea

power, however, did not project on land. Land wars fought between the major

powers include the Crimean War, the Franco-Austrian War, the Austro-Prussian War and

the Franco-Prussian War, as well as

numerous conflicts between lesser powers. The Royal Navy prosecuted the First

Opium War (1839–1842) and Second Opium War (1856–1860)

against Imperial China. The Royal Navy was superior to

any other two navies in the world, combined. Only Germany was a potential naval

threat.

Britain traded goods and capital extensively

with countries around the world, adopting a free trade policy after 1840. The

growth of British imperial strength was further underpinned by the steamship and

the telegraph, new technologies invented in the second half of the

19th century, allowing it to control and defend the empire. By 1902, the

British Empire was linked together by a network of telegraph cables, the

so-called All Red Line.

The Pax

Britannica was weakened by the breakdown of the continental order

which had been established by the Congress of Vienna. Relations between the Great Powers of Europe were strained to

breaking point by issues such as the decline of the Ottoman Empire, which led to

the Crimean War, and later the emergence of new nation states in the

form of Italy and Germany after the Franco-Prussian War. Both of

these wars involved Europe's largest states and armies. The industrialisation

of Germany, the Empire of Japan, and

the United States contributed to the relative decline of British

industrial supremacy in the early 20th century.

An

elaborate map of the British Empire in 1886, marked in the traditional colour

for

imperial

British dominions on maps

C. Empire

expands - in 1867, Britain united most of

its North

American colonies as the Dominion of Canada, giving it

self-government and responsibility for its own defence, but Canada did not have

an independent foreign policy until 1931. Several of the colonies temporarily

refused to join the Dominion despite pressure from both Canada and Britain; the

last one, Newfoundland, held out

until 1949. The second half of the 19th century saw a huge

expansion of Britain's colonial empire, mostly in Africa. A talk of the Union Jack flying "from Cairo to

Cape Town" only became a reality at the end of the Great War. Having

possessions on six continents, Britain had to defend all of its empire and did

so with a volunteer army, the only great power in

Europe to have no conscription. Some questioned whether the country was

overstretched.

The rise of

the German Empire since

its creation in 1871 posed a new challenge, for it (along with the United

States), threatened to usurp Britain's place as the world's foremost industrial

power. Germany acquired a number of colonies in Africa and the Pacific, but

Chancellor Otto

von Bismarck succeeded in achieving general peace through his

balance of power strategy. When William

II became emperor in 1888, he discarded Bismarck, began using bellicose

language, and planned to build a navy to rival Britain's.

Ever since

Britain had wrested control of the Cape Colony from the

Netherlands during the Napoleonic Wars, it had

co-existed with Dutch settlers who had migrated further away from the Cape and created

two republics of their own. The British imperial vision called for control over

these new countries, and the Dutch-speaking "Boers" (or

"Afrikaners") fought back in the War in 1899–1902. Outgunned by

a mighty empire, the Boers waged a guerrilla war (which certain other British

territories would later employ to attain independence). This gave the British

regulars a difficult fight, but their weight of numbers, superior equipment,

and often brutal tactics, eventually brought about a British victory. The war

had been costly in human rights and was widely criticised by Liberals in

Britain and worldwide. However, the United States gave its support. The Boer

republics were merged into the Union

of South Africa in 1910; this had internal self-government, but

its foreign policy was controlled by London and it was an integral part of the

British Empire.

Imperialism - after the loss of the

American colonies in 1776, Britain built a "Second British Empire",

based in colonies in India, Asia, Australia, Canada. The crown jewel was India,

where in the 1750s a private British company, with its own army, the East

India Company (or "John Company"), took control of parts of India. The

19th century saw Company rule extended across India after expelling the Dutch, French

and Portuguese. By the 1830s the Company was a government and had given up most

of its business in India, but it was still privately owned. Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857 the government closed down the

Company and took control of British

India and the Company's Presidency

Armies.

Free trade (with no tariffs and few trade

barriers) was introduced in the 1840s. Protected by the overwhelming power of

the Royal Navy, the economic empire included very close economic ties with

independent nations in Latin America. The informal economic empire has been

called "The Imperialism of Free Trade."

Numerous independent entrepreneurs

expanded the Empire, such as Stamford

Raffles of the East India

Company who founded the port of Singapore in 1819. Businessmen eager to sell

Indian opium in the vast China market led to the Opium War (1839–1842) and the

establishment of British colonies at Hong Kong. One adventurer, James

Brooke, set himself up as the

Rajah of the Kingdom

of Sarawak in North Borneo in

1842; his realm joined the Empire in 1888. Cecil

Rhodes set up an economic

empire of diamonds in South Africa that proved highly profitable. There were

great riches in gold as well but this venture led to expensive wars with

the Dutch settlers known as Boers.

The possessions of the East India Company in

India, under the direct rule of the Crown from 1857 —known as British India—

was the centerpiece of the Empire, and because of an efficient taxation system

it paid its own administrative expenses as well as the cost of the large British Indian Army. In terms of trade, however, India turned

only a small profit for British business.

There was pride and glory in the Empire,

as the most talented young Britons vied for positions in the Indian Civil Service and for similar oversees career

opportunities. The opening of the Suez

Canal in 1869 was a

vital economic and military link. To protect the canal, Britain expanded

further, taking control of Egypt, the Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, Cyprus, Palestine,

Aden, and British Somaliland. None were especially profitable until the

discovery of oil in the Middle East after 1920. Some military action was

involved, and from time to time there was a risk of conflict with other

imperial powers seeking the same territory, as in the Fashoda

Incident of 1898. All the

incidents were resolved peacefully.

Cain and Hopkins argue that the phases of

expansion abroad were closely linked with the development of the domestic

economy. Therefore, the shifting balance of social and political forces under

imperialism and the varying intensity of Britain's economic and political

rivalry with other powers need to be understood with reference to domestic

policies. Gentlemen capitalists, representing Britain's landed gentry and

London's service sectors and financial institutions, largely shaped and

controlled Britain's imperial enterprises in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Industrial leaders played a lesser role and found themselves dependent on the

gentlemen capitalists.

CHRONOLOGY OF VICTORIAN ERA

1837 - Death of King William IV at Windsor. He is succeeded by his niece, Victoria. Births, deaths and marriages must be registered by law. Charles Dickens publishes 'Oliver Twist,' drawing attention to Britain's poor.

1838 - The Anti-Corn Law League is established. Publication of the People's Charter. The start of Chartism

1839

- Chartist Riots take place

1840 - Queen Victoria marries Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. The penny post is instituted

1841 - The first British Census recording the names of the populace is undertaken. The Tories come to power. Sir Robert Peel becomes Prime Minister

1840 - Queen Victoria marries Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. The penny post is instituted

1841 - The first British Census recording the names of the populace is undertaken. The Tories come to power. Sir Robert Peel becomes Prime Minister

1844

- Parliament passes the Bank Charter Act. Foundation of the Rochdale

Co-Operative Society and the Royal Commission on the Health of Towns

1844-45 - Railways mania explodes across Britain. Massive investment and speculation leads to the laying of 5,000 miles of track

1845-49 - Irish Potato Famine kills more than a million people

1846 - End of Sir Robert Peel's Ministry. Whigs come to Power. Repeal of the Corn Laws

1848 - Major Chartist demonstration in London. Revolutions in Europe. Parliament passes the Public Health Act

1844-45 - Railways mania explodes across Britain. Massive investment and speculation leads to the laying of 5,000 miles of track

1845-49 - Irish Potato Famine kills more than a million people

1846 - End of Sir Robert Peel's Ministry. Whigs come to Power. Repeal of the Corn Laws

1848 - Major Chartist demonstration in London. Revolutions in Europe. Parliament passes the Public Health Act

1851

- The Great Exhibition is staged in Hyde Park. Thanks to Prince Albert, it is a

great success

1852 - Death of the Duke of Wellington. Derby's first minority Conservative government. Aberdeen's coalition government is established

1853 - Vaccination against smallpox is made compulsory. Queen Victoria uses chloroform during birth of Prince Leopold. Gladstone presents his first budget

1854 - The Northcote-Trevelyan civil service report is published The Crimean War begins, as Britain and France attempt to defend European interests in the Middle East against Russia

1855 - End of Aberdeen's coalition government. Palmerston's first government comes to power

1856 - Crimean War comes to an end. The Victoria Cross is instituted for military bravery

1857-58 - The Second Opium War opens China to European trade. The Indian Mutiny erupts against British Rule on the sub-continent

1852 - Death of the Duke of Wellington. Derby's first minority Conservative government. Aberdeen's coalition government is established

1853 - Vaccination against smallpox is made compulsory. Queen Victoria uses chloroform during birth of Prince Leopold. Gladstone presents his first budget

1854 - The Northcote-Trevelyan civil service report is published The Crimean War begins, as Britain and France attempt to defend European interests in the Middle East against Russia

1855 - End of Aberdeen's coalition government. Palmerston's first government comes to power

1856 - Crimean War comes to an end. The Victoria Cross is instituted for military bravery

1857-58 - The Second Opium War opens China to European trade. The Indian Mutiny erupts against British Rule on the sub-continent

1858

- Derby establishes his second minority government. Parliament passes the India

Act

1859

- End of Derby's second minority government. Palmerston brings his second

Liberal government to power. Charles Darwin publishes his 'The Origin of the

Species'

1860 - Gladstone's budget and the Anglo-French Cobden Treaty codifies and extends the principles of free trade

1861 - Death of Prince Albert, Prince Consort

1862 - Parliament passes the Limited Liability Act in order to provide vital stimulus to accumulation of capital in shares

1860 - Gladstone's budget and the Anglo-French Cobden Treaty codifies and extends the principles of free trade

1861 - Death of Prince Albert, Prince Consort

1862 - Parliament passes the Limited Liability Act in order to provide vital stimulus to accumulation of capital in shares

1863

- Edward, Prince of Wales, marries Princess Alexandra of Denmark. The Salvation

Army is founded

1865 - Death of Palmerston. Russell establishes his second Liberal government

1866 - Russell and Gladstone fail to have their moderate Reform Bill passed in parliament. Derby takes power in his third minority Conservative government

1867 - Derby and Disraeli's Second Reform Bill doubles the franchise to two million. Canada becomes the first independent dominion in the British Empire under the Dominion of Canada Act

1868 - Disraeli succeeds Derby as Prime Minister. Gladstone becomes Prime Minister for the first time

1869 - The Irish Church is disestablished. The Suez Canal is opened

1870 - Primary education becomes compulsory in Britain through the Forster-Ripon English Elementary Education Act. Parliament also passes the Women's Property Act, extending the rights of married women, and the Irish Land Act

1865 - Death of Palmerston. Russell establishes his second Liberal government

1866 - Russell and Gladstone fail to have their moderate Reform Bill passed in parliament. Derby takes power in his third minority Conservative government

1867 - Derby and Disraeli's Second Reform Bill doubles the franchise to two million. Canada becomes the first independent dominion in the British Empire under the Dominion of Canada Act

1868 - Disraeli succeeds Derby as Prime Minister. Gladstone becomes Prime Minister for the first time

1869 - The Irish Church is disestablished. The Suez Canal is opened

1870 - Primary education becomes compulsory in Britain through the Forster-Ripon English Elementary Education Act. Parliament also passes the Women's Property Act, extending the rights of married women, and the Irish Land Act

1871

- Trade Unions are legalized

1872 - Secret voting is introduced for elections. Parliament passes the Scottish Education Act

1873 - Gladstone's government resigns after the defeat of their Irish Universities Bill. Disraeli declines to take up office instead

1874 - Disraeli becomes Conservative Prime Minister for the second time

1875 - Disraeli purchases a controlling interest for Britain in the Suez Canal. Agricultural depression increases

1875-76 - Parliament passes R.A. Cross's Conservative social reforms

1876 - Queen Victoria becomes Empress of India. The massacre of Christians in Turkish Bulgaria leads to anti-Turkish campaigns in Britain, led by Gladstone

1877 - Confederation of British and Boer states established in South Africa

1878 - The Congress of Berlin is held. Disraeli announces 'peace with honour'

1879 - A trade depression emerges in Britain. The Zulu War is fought in South Africa. The British are defeated at Isandhlwana, but are victorious at Ulundi

1879-80 - Gladstone's Midlothian campaign denounces imperialism in South Africa and Afghanistan

1872 - Secret voting is introduced for elections. Parliament passes the Scottish Education Act

1873 - Gladstone's government resigns after the defeat of their Irish Universities Bill. Disraeli declines to take up office instead

1874 - Disraeli becomes Conservative Prime Minister for the second time

1875 - Disraeli purchases a controlling interest for Britain in the Suez Canal. Agricultural depression increases

1875-76 - Parliament passes R.A. Cross's Conservative social reforms

1876 - Queen Victoria becomes Empress of India. The massacre of Christians in Turkish Bulgaria leads to anti-Turkish campaigns in Britain, led by Gladstone

1877 - Confederation of British and Boer states established in South Africa

1878 - The Congress of Berlin is held. Disraeli announces 'peace with honour'

1879 - A trade depression emerges in Britain. The Zulu War is fought in South Africa. The British are defeated at Isandhlwana, but are victorious at Ulundi

1879-80 - Gladstone's Midlothian campaign denounces imperialism in South Africa and Afghanistan

1880

- Gladstone establishes his second Liberal government

1880-81

- The first Anglo-Boer War is fought

1881 - Parliament passes the Irish Land and Coercion Acts

1882 - Britain occupies Egypt. A triple alliance is established between Germany, Austria and Italy

1884 - Parliament passes the third Reform Act which further extends the franchise

1885 - Death of General Gordon at Khartoum. Burma is annexed. Salisbury succeeds Gladstone with his first minority Conservative government. Parliament passes the Redistribution Act

1886 - Gladstone's third Liberal government fails to pass its first Irish Home Rule Bill through the House of Commons. Gladstone resigns as Prime Minister. Split in the Liberal Party. Salisbury establishes his second Conservative-Liberal-Unionist government. The Royal Niger Company is chartered. Gold is discovered in the Transvaal

1887 - Queen Victoria celebrates her Golden Jubilee. The Independent Labour Party is founded. The British East Africa Company is chartered

1881 - Parliament passes the Irish Land and Coercion Acts

1882 - Britain occupies Egypt. A triple alliance is established between Germany, Austria and Italy

1884 - Parliament passes the third Reform Act which further extends the franchise

1885 - Death of General Gordon at Khartoum. Burma is annexed. Salisbury succeeds Gladstone with his first minority Conservative government. Parliament passes the Redistribution Act

1886 - Gladstone's third Liberal government fails to pass its first Irish Home Rule Bill through the House of Commons. Gladstone resigns as Prime Minister. Split in the Liberal Party. Salisbury establishes his second Conservative-Liberal-Unionist government. The Royal Niger Company is chartered. Gold is discovered in the Transvaal

1887 - Queen Victoria celebrates her Golden Jubilee. The Independent Labour Party is founded. The British East Africa Company is chartered

1888 - The County Councils' Act establishes representative county based authorities

1889 - London Dockers' Strike. The British South Africa Company is chartered

1892 - Gladstone forms his fourth Liberal government

1893 - Second Irish Home Rule Bill fails to pass the House of Lords

1894 - Rosebery takes power with his minority Liberal government

1895 - Salisbury forms his third Unionist ministry

1896

- The British conquest of the Sudan begins

1897 - Queen Victoria celebrates her Diamond Jubilee

1898 - British rule over Sudan fully established. German Naval expansion begins

1899 - British disasters in South Africa

1899-1902 - Boer War in South Africa

1900 - Salisbury wins the Khaki election. The Labour Representation Committee is formed. Parliament passes the Commonwealth of Australia Act

1901 - Death of Queen Victoria. She is succeeded by her son, Prince Albert, as King Edward VI

1897 - Queen Victoria celebrates her Diamond Jubilee

1898 - British rule over Sudan fully established. German Naval expansion begins

1899 - British disasters in South Africa

1899-1902 - Boer War in South Africa

1900 - Salisbury wins the Khaki election. The Labour Representation Committee is formed. Parliament passes the Commonwealth of Australia Act

1901 - Death of Queen Victoria. She is succeeded by her son, Prince Albert, as King Edward VI

No comments:

Post a Comment