1. The House of Plantagenet

A. General characteristic of the house of Plantagenet - the House of Plantagenet was a royal house which originated from the lands of Anjou in France. The name Plantagenet is used by modern historians to identify four distinct royal houses – the Angevins who were also Counts of Anjou, the main body of the Plantagenets following the loss of Anjou, and the houses of Lancaster and York, the Plantagenets' two cadet branches. The family held the English throne from 1154, with the accession of Henry II, until 1485, when Richard III died.

Under the

Plantagenets, England was transformed, although this was only partly

intentional. The Plantagenet kings were often forced to negotiate compromises

such as Magna

Carta. These constrained royal power in return for financial and military

support. The king was no longer just the most powerful man in the nation,

holding the prerogative of judgement, feudal tribute and warfare. He now had

defined duties to the realm, underpinned by a sophisticated justice system. A

distinct national identity was shaped by conflict with the French, Scots, Welsh

and Irish, and the establishment of English as the primary language.

In the 15th

century, the Plantagenets were defeated in the Hundred Years' War and

beset with social, political and economic problems. Popular revolts were

commonplace, triggered by the denial of numerous freedoms. English nobles

raised private armies, engaged in private feuds and openly defied Henry VI.

The rivalry

between the House of Plantagenet's two cadet branches of York and Lancaster

brought about the Wars of the Roses, a

decades-long fight for the English succession, culminating in the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485,

when the reign of the Plantagenets and the English Middle Ages both met

their end with the death of King Richard III. Henry VII, a

Lancastrian, became king of England; two years later, he married Elizabeth

of York, thus ending the Wars of the Roses, and giving rise to the Tudor dynasty. The Tudors

worked to centralise English royal power, which allowed them to avoid some of

the problems that had plagued the last Plantagenet rulers. The resulting

stability allowed for the English Renaissance, and the

advent of early modern Britain.

B. Main representatives of the dynasty to Hundred Years' War (1154-1337)

William II, Rufus (1087-1100) - despite the cohesion and order brought to England by the Duke of Normandy, the new administrative system outlived him by less than fifty years. Though William respected the elective nature of the English monarch, perfunctorily recognised at his own coronation, on his deathbed in Normandy he handed over the crown to William Rufus, his favourite son, and sent him to England to Archbishop Lanfranc. He reluctantly granted the Duchy of Normandy to Robert, his eldest, and bequeathed a modest sum to Henry Beauclerk, his youngest. There were bound to be problems.

William II, Rufus (1087-1100) - despite the cohesion and order brought to England by the Duke of Normandy, the new administrative system outlived him by less than fifty years. Though William respected the elective nature of the English monarch, perfunctorily recognised at his own coronation, on his deathbed in Normandy he handed over the crown to William Rufus, his favourite son, and sent him to England to Archbishop Lanfranc. He reluctantly granted the Duchy of Normandy to Robert, his eldest, and bequeathed a modest sum to Henry Beauclerk, his youngest. There were bound to be problems.

| The second Norman king of England, William II, King Rufus, who was killed in August 1100 |

The

dominions ruled by William lI, Rufus, were closely knit together by the family.

The King of England and the Duke of Normandy had rival claims upon the

allegiance of every great land-holder from the Scottish borders to Anjou. And

these great land-holders, the Barons and Earls made it their business to

provoke and protract quarrels of every kind between their rulers. It was a

rotten state of affairs that could only be settled through the English

acquisition of Normandy. In addition, Norman lands were surrounded by enemies

eager to re-conquer lost territories. One of these foes was the Church of Rome

itself, rapidly increasing in power and prestige at the expense of the feudal

monarchies. Both William Rufus and his successor Henry I had to deal with problems

that eventually lay beyond their capabilities to solve.

The

leading Barons acquiesced in the coronation of William Rufus by Lanfranc in

September of 1087, taking their lead from the archbishop but also demonstrating

the immense power that was accruing to the Church in England. The new king was

an illiterate, avaricious, impetuous man, not the sort of ruler the country

needed at this or at any other time. According to William of Malmesbury, he had

already sunk below the possibility of greatness or moral reformation. It seems

that the only profession he honoured was that of war; his court became a Mecca

for those practiced in its arts; his retainers lived lavishly off the land and

took what they wished from whom they wished. To entertain his retinue, the king

had a huge banqueting hall built in Westminster.

|

| Death of William Rufus in a hunting accident |

Despite

the faults of William ll, England was governed well compared to Normandy, where

a constant state of anarchy prevailed and where Duke Robert was unable to

control his barons who waged private wars, built castles without license and

acted as petty, independent sovereigns.

Henry

I (1100-1135) - of the three sons of the Conqueror, Henry was the

most able. A competent administrator at home, he succeeded in the conquest of

Normandy.

Also known as Henry Beauclerc, was King of England from

1100 to his death. Henry was the fourth son of William

the Conqueror and was educated in Latin and the liberal arts. On William's

death in 1087, Henry's elder brothers Robert Curthose and William

Rufus inherited Normandy and

England, respectively, but Henry was left landless. Henry purchased the County of Cotentin in

western Normandy from Robert, but William and Robert deposed him in 1091. Henry

gradually rebuilt his power base in the Cotentin and allied himself with

William against Robert. Henry was present when William died in a hunting

accident in 1100, and he seized the English throne, promising at his coronation

to correct many of William's less popular policies. Henry married Matilda

of Scotland but continued to have a large number of mistresses, by whom he had

many illegitimate children.

Robert, who

invaded in 1101, disputed Henry's control of England; this military campaign

ended in a negotiated settlement that confirmed Henry as king. The peace was

short-lived, and Henry invaded the Duchy of Normandy in 1105 and 1106, finally

defeating Robert at the Battle

of Tinchebray.

Henry kept Robert imprisoned for the rest of his

life. Henry's control of Normandy was challenged by Louis VI of France, Baldwin

of Flanders and Fulk

of Anjou, who promoted the rival claims of Robert's son, William Clito, and supported

a major rebellion in the Duchy between 1116 and 1119. Following Henry's victory

at the Battle

of Brémule, a favourable peace settlement was agreed with Louis in 1120.

|

| Late medieval picture from the 15th century of the Battle of Tinchebray |

Considered by

contemporaries to be a harsh but effective ruler, Henry skilfully manipulated

the barons in England and Normandy. In England, he drew on the existing Anglo-Saxon system

of justice, local government and taxation, but also strengthened it with

additional institutions, including the royal exchequer and

itinerant justices. Normandy was

also governed through a growing system of justices and an exchequer. Many of

the officials who ran Henry's system were "new men" of obscure

backgrounds rather than from families of high status, who rose through the

ranks as administrators.

Considered by

contemporaries to be a harsh but effective ruler, Henry skilfully manipulated

the barons in England and Normandy. In England, he drew on the existing Anglo-Saxon system

of justice, local government and taxation, but also strengthened it with

additional institutions, including the royal exchequer and

itinerant justices. Normandy was

also governed through a growing system of justices and an exchequer. Many of

the officials who ran Henry's system were "new men" of obscure

backgrounds rather than from families of high status, who rose through the

ranks as administrators. Henry encouraged ecclesiastical reform, but became embroiled in a serious dispute in 1101 with Archbishop Anselm of Canterbury, which was resolved through a compromise solution in 1105. He supported the Cluniac order and played a major role in the selection of the senior clergy in England and Normandy.

Henry's only

legitimate son and heir, William Adelin, drowned in

the White Ship disaster

of 1120, throwing the royal succession into doubt. Henry took a second

wife, Adeliza, in the hope

of having another son, but their marriage was childless. In response to this,

Henry declared his daughter, Matilda, his heir and

married her to Geoffrey of Anjou. The

relationship between Henry and the couple became strained, and fighting broke

out along the border with Anjou. Henry died on 1 December 1135 after a week of

illness. Despite his plans for Matilda, the King was succeeded by his

nephew, Stephen

of Blois, resulting in a period of civil war known as the

Anarchy.

Henry

II (1154-1189) - Henry had become Duke of Normandy in 1150 and Count

of Anjou after his father's death in 1151. When he married Eleanor of Aquitaine

in 1152, he ruled her duchy as well, thus becoming more powerful than his lord,

King Louis of France. Eleanor had been divorced from Louis VII after her spell

of adultery with her Uncle Raymond of Antioch, notwithstanding the efforts of

the Pope to keep the marriage whole. She was several years older than Henry,

but she was determined on the union and made all the initial overtures. The

turbulent marriage of the able, headstrong, ambitious Henry to an older woman,

equally ambitious and proud, was famous for its political results.

Henry

II

King

Louis, fearful of his loss of influence in France, made war on the couple,

joined by Henry's younger brother Geoffrey who claimed the inheritance of

Anjou. Their feeble opposition, however, was easily overcome and Henry acquired

a vast swathe of territory in France from Normandy through Anjou to Aquitaine.

The stage was set for the greatest period in Plantagenet history.

Henry

II was one of the most powerful rulers in Europe. His boundless energy was the

wonder of his chroniclers; his court had to rush like mad to keep up with his

constant travels and hunting expeditions. But he was also a scholar and

Churchman, founding and endowing many religious houses, though he was castigated

for keeping many bishoprics vacant to enjoy their revenues for himself. To

posterity, he left a legacy of shrewd decisions in the effective legal,

administrative and financial developments of his thirty-five year reign.

Upon

his succession, Henry immediately took steps to reduce the power of the barons,

who had built up their estates and consolidated their positions during the

anarchy under Stephen. He refused to recognize any land grants made by his

predecessor and ruled as if Stephen had not even existed. Any attempts at

opposition were suppressed so that by 1158, four years into his reign, he ruled

supreme in England.

Henry

then turned his attention to the Church, shrewdly relying on his close ally

Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury to carry out his religious policies. England

began to prosper under its able administrators closely watched and guided by

their king. Particularly noticeable were the growth of boroughs, the new towns

that were to transform the landscape of the nation during the century and that

were ultimately to play such a strong part in its political and economic life.

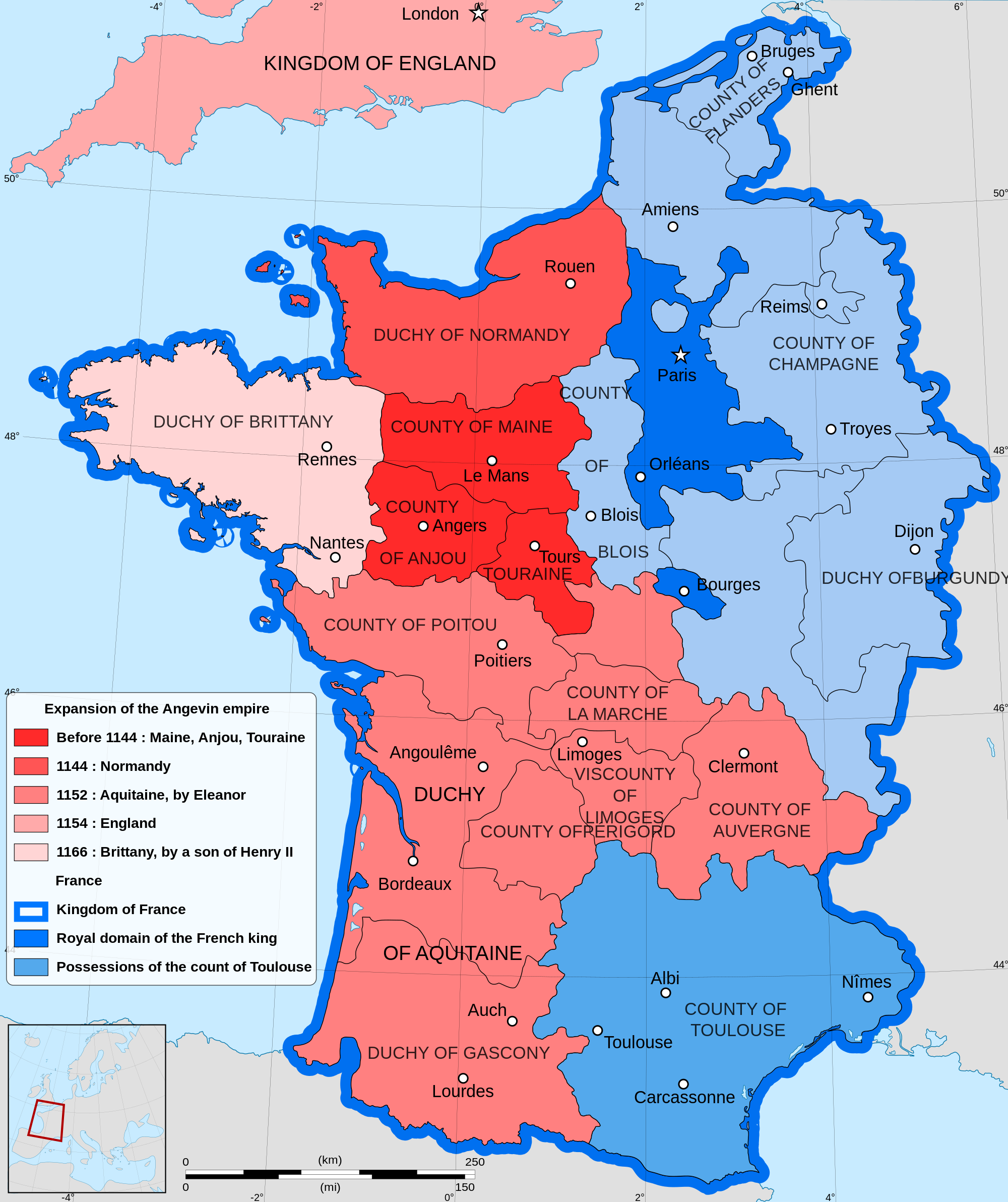

Henry's

continental holdings in 1154

The

growth of towns, the new trading centres, was greatly aided by the stimulation

of the First Crusade that revived the commerce of Europe by increased contact

with the Mediterranean and especially through the growth of Venice.

Improvements in agriculture included the introduction of the wheeled plough and

the horse collar, both of which were to have enormous influence on farming

methods and transportation. For one thing, the horse collar made it possible to

efficiently transport the heavy blocks of stone for the building of the great

cathedrals. The drift into towns meant a weakening of serfdom and the Lord's

hold upon his demesne; serfs left the land to become traders, peddlers and

artisans.

Great

changes in Europe also had their effects on the English political system.

Motivated by hatred and fear of the Muslems, and stimulated by the Crusades,

the Italian city-states grew in influence and prosperity. Sicily had been

conquered by the Normans by 1090, opening up the Western Mediterranean to

trade. This in turn stimulated the growth of the towns, which soon led to

demands for more say in their own government and the inevitable clash with the

Church, ever anxious to protect its own areas of interest and those of the

merchant classes and rapidly forming guilds.

The continuing clash between Church and King was another matter altogether. There seem to have been three main factors in the quarrel between Archbishop Becket and King Henry: their differing personalities, political implications and the intolerance of the age. As chancellor for eight years from 1154, Becket was a firm friend of the king with whom he had been a boyhood companion. He was energetic, methodical and trustworthy, supporting his king in relations with the Church. There was hardly any indication that the relationship of Church and State would be completely changed upon Becket's appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury upon Theodore's death in 1161, a position in which he now displayed the same enthusiasm and energy as before, but now sworn to uphold ecclesiastical prestige against any royal encroachments. Resigning the chancellorship, he began in earnest to work solely in the interests of the Church, opposing the king even on insignificant, trivial matters, but especially over Henry's proposal that people in holy orders found guilty of criminal offences should be handed over to the secular authorities for punishment.

The continuing clash between Church and King was another matter altogether. There seem to have been three main factors in the quarrel between Archbishop Becket and King Henry: their differing personalities, political implications and the intolerance of the age. As chancellor for eight years from 1154, Becket was a firm friend of the king with whom he had been a boyhood companion. He was energetic, methodical and trustworthy, supporting his king in relations with the Church. There was hardly any indication that the relationship of Church and State would be completely changed upon Becket's appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury upon Theodore's death in 1161, a position in which he now displayed the same enthusiasm and energy as before, but now sworn to uphold ecclesiastical prestige against any royal encroachments. Resigning the chancellorship, he began in earnest to work solely in the interests of the Church, opposing the king even on insignificant, trivial matters, but especially over Henry's proposal that people in holy orders found guilty of criminal offences should be handed over to the secular authorities for punishment.

The

king was determined to turn unwritten custom into written, thus making Becket

liable for punishment, but Henry's insistence that it was illegal for Churchmen

to appeal to Rome gave the quarrel a much wider significance. After Henry had

presented his proposals at Clarendon in January 1164, Becket refused to submit

and his angry confrontation with the king was only defused with his escape to

exile in France to wage a war of words. He found very little support from the

English bishops who owed their appointments to royal favour and who were

heavily involved on the Crown's behalf in legal and administrative matters.

They were not willing to give up their powers by supporting the Archbishop,

whose intransigence made him, in their eyes, a fool. After six years in exile,

however, a compromise was reached and Becket returned to England.

| Murdering of Thomas Becket |

Showing

not a sign of his willingness to honour the compromise, Becket immediately

excommunicated the Archbishop of York and the other bishops who had assisted at

the coronation of Henry's oldest son. When the news reached Henry in Normandy,

his anger was uncontrollable and the four knights who sped to Canterbury to

murder Becket in his own cathedral thought that this was an act desired by the

King. Instead, the whole of Europe was outraged.

The

dead archbishop was immensely more powerful than the live one, and more than

Henry's abject penance made the murdered Becket the most influential martyr in

the history of the English Church. The triangle of Pope, King and Archbishop was

broken. Canon law was introduced fully into England, and an important phase in

the struggle between Church and State had been won. Henry was forced to give

way all along the line; as a way out, he busied himself in Ireland, sending his

son John as "Lord of Ireland" to conduct a campaign that was a

complete fiasco.

Taking

advantage of their father's weakness, his sons now broke out in open rebellion,

aided by the Queen, though their lack of cooperation and trust in each other

led to Henry eventually being able to defeat them one at a time. For her part,

Eleanor was imprisoned for the remainder of the king's life. During her

husband's many absences, she had acted as regent of England. Her particular

ally against Henry was Richard, heir to the duchy of Aquitaine. During the last

three years of Henry's life, his imprisoned queen once more began to plot

against him, and upon his death in 1189, she assumed far greater powers than

she had enjoyed as his queen.

Under

pressure from resistance in Britanny and Aquitaine, and possible rebellion from

his sons, aided by their ambitious, scheming mother, Henry had worked out a

scheme for the future division of his kingdoms. Henry was to inherit England,

Normandy and Anjou;

Richard

was to gain Poitou and Britanny was to go to Geoffrey. John was to get nothing,

but later was promised Chinon, Loudon and Mirebeau as part of a proposed

marriage settlement. This decision was strongly contested by Prince Henry and

was a leading factor in the warfare that ensued between the King and his sons.

It was in Normandy that Henry fell ill; he died after being forced to accept

humiliating terms from Philip of France and his son Richard, who succeeded him

as King of England in 1189.

Richard

l (1189-1199) - showing

but some of his father's administrative capacity, Richard I, the Lionheart,

preferred to demonstrate his talents in battle. His ferocious pursuit of the

arts of war squandered his vast wealth and devastated the economy of his

dominions. On a Crusade to the Holy Land in 1191-2, he was captured while

returning to England and ransomed in prison in Austria. But upon his release,

he went back to fighting, this time against Philip II of France. In a minor

skirmish in Aquitaine, he was killed. That almost sums up his reign, but not

quite.

King

Richard spent all of six months in England. To raise the funds for his

adventures overseas, however, he appointed able administrators who carried out

his plans to sell just about everything he owned: offices, lordships, earldoms,

sheriffdoms, castles, towns, and lands. Even his Chancellor William Longchamps,

Bishop of Ely, had to pay an enormous sum for his chancellorship. William also

taxed the people heavily in the service of his master, making himself extremely

unpopular and being removed by a rebellion of the Barons in 1191.

|

| The Near East in 1190 (Cyprus in purple) |

One

favourable legacy that Richard left behind was his patronage of the

troubadours, the composers of lyric poetry that were bringing a civilized tone

to savage times and whose influence charted the future course that literature

in Europe was to take. A sad note is that Richard's preparations for the Third

Crusade against the Muslims provoked popular hostility in England towards its

Jewish inhabitants (who had been formerly encouraged to come from Normandy). A

massacre of the Jewish inhabitants of York took place in March, 1190, and

Richard's successor, John placed heavy fines which led to many Jews fleeing

back to the continent, a process that continued into the reign of Edward I,

when they were expelled from England.

King John (1199-1216) - there are quite a number of

ironies connected with the reign of John, for during his reign all the vast

Plantagenet possessions in France except Gascony were lost. From now on, the House

of Anjou was separated from its links with its homeland, and the Crown of

England eventually could concern itself solely with running its own affairs

free from Continental intrigue. But that was later.

|

| The Angevin continental empire (orange shades) in the late 12th century |

In

the meantime, John's mishandling of his responsibilities at home led to

increased baronial resistance and to the great concessions of the Magna Carta,

hailed as one of the greatest developments in human rights in history and the

precursor of the United States Bill of Rights. It was also in John's reign that

the first income tax was levied in England. To try to recover his lost lands in

France, John introduced his tax of one thirteenth on income from rents and

moveable property, to be collected by the sheriffs.

To

be fair to the unfortunate John, his English kingdom had been drained of its

wealth for Richard's wars in France and the Crusade as well as the exorbitant

ransom. His own resources were insufficient to overcome the problems he thus

inherited. He also lacked the military abilities of his brother. It has been

said that John could win a battle in a sudden display of energy, but then

fritter away any advantage gained in a spell of indolence. It is more than one

historian who wrote of John as having the mental abilities of a great king, but

the inclinations of a petty tyrant.

Innocent,

Pope from 1198 to 1216 was the first to style himself "Vicar of

Christ." He proved to be a formidable adversary to the English King. Their

major dispute came over the appointment of the new Archbishop of Canterbury at

the death of Hubert Walter in 1205. John refused to accept Stephen Langton, an

Englishman active in the papal court at Rome. He was punished by the Interdict

of 1208, and for the next five years, English priests were forbidden from

administering the sacraments, even from burying the dead. Most of the bishops

left the country.

For

posterity, however, the two most important clauses were 39, which states that

no one should be imprisoned without trial and 40, which states that no one

could buy or deny justice.

|

| A romanticised 19th-century recreation of King John signing the Magna Carta |

Edward

I (1272-1307) - seen by many historians as the ideal medieval king,

Edward l enjoyed warfare and statecraft equally. Known as Edward Longshanks, he

was a man whose immense strength and steely resolve had been ably shown on the

crusade he undertook to the Holy Land in 1270.

|

| Operations during the Crusade of Edward I |

| Edward I |

|

| Reconstruction of Conwy Castle and town walls at the end of the 13th century |

The

stubborn Welsh were a thorn in the side of Edward whose ambition was to rule

the whole of Britain. They were a proud people, considering themselves the true

Britons. Geoffrey of Monmouth (1090-1155) had claimed that they had come to the

island of Britain from Troy under their leader Brutus. He also praised their

history, written in the British tongue (Welsh). Another Norman-Welsh author,

Giraldus Cambrensis (1146-1243) had this to say about his fellow countrymen:

The

English fight for power: the Welsh for liberty; the one to procure, gain, the

other to avoid loss. The English hirelings for money; the Welsh patriots for

their country. When the English nation forged some kind of national identity

under Alfred of Wessex, the Welsh put aside their constant infighting to create

something of a nation themselves under a succession of strong leaders beginning

with Rhodri Mawr (Rhodri the Great) who ruled the greater part of Wales by the

time of his death in 877. Rhodri's work of unification was then continued by

his grandson, Hywel Dda (Howell the Good 904-50), whose codification of Welsh

law has been described as among the most splendid creations of the culture of

the Welsh.

Under

Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, Wales was forged into a single political unit. In 1204,

Llywelyn married King John's daughter Joan and was recognised by Henry III as

preeminent in his territories. At his death, however, in 1240, fighting between

his sons Dafydd and Gruffudd just about destroyed all their father had

accomplished, and in 1254, Henry's son Edward was given control of all the

Crown lands in Wales that had been ceded at the Treaty of Woodstock in 1247.

The

situation was restored by Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, recognised as Prince of Wales

by Henry in 1267 and ruler of a kingdom set to conduct its own affairs free

from English influence. The tide of affairs then undertook a complete reversal

with the accession of Edward I to the throne of England in 1272.

Edward's

armies were defeated when they first crossed Offas's Dyke into Wales. The

English king's determination to crush his opposition, his enormous expenditure

on troops and supplies and resistance to Llywelyn from minor Welsh princes who

were jealous of his rule, soon meant that the small Welsh forces were forced

into their mountain strongholds. At the Treaty of Aberconwy of 1287, Llywelyn

was forced to concede much of his territories east of the River Conwy. Edward

then began his castle-building campaign, beginning with Flint right on the

English border and extending to Builth in mid-Wales.

At

the Statute of Rhuddlan, 1284, Wales was divided up into English counties; the

English court pattern set firmly in place, and for all intents and purposes,

Wales ceased to exist as a political unit. The situation seemed permanent when

Edward followed up his castle building program by his completion of Caernarfon,

Conwy and Harlech. In 1300, Edward made his son (born at Caernarfon castle, in

that mighty fortress overlooking the Menai Straits in Gwynedd) "Prince of

Wales." The powerful king could now turn his attention to those other

troublemakers, the Scots.

Wales

after the Treaty of Montgomery 1267

The Scots' Road to Independence

1. Effects

of Viking Conquest: at roughly the same time that the people of Wales were

separated from the invading Saxons by the artificial boundary of Offa's Dyke,

MacAlpin had been creating a kingdom of Scotland. His successes in part were

due to the threat coming from the raids of the Vikings, many

of whom became settlers. The seizure of control over all Norway in 872 by

Harald Fairhair caused many of the previously independent Jarls to look for new

lands to establish themselves. One result of the coming of the Norsemen and

Danes with their command of the sea, was that Scotland became surrounded and

isolated. The old link with Ireland was broken and the country was now cut off

from southern England and the Continent, thus the kingdom of Alba established

by MacAlpin was thrown in upon itself and united against a common foe.

2. Interaction

with the Normans: it was under the rule of David l, the ninth son of Malcom

III, that Norman influence began to percolate through much of southern

Scotland. David, King of Scotland, was also Prince of Cumbria, and through

marriage, Earl of Northampton and Huntingdon. Brother-in-law to the King of

England, he was raised and educated in England by Normans who "polished

his manners from the rust of Scottish barbarity." In Scotland, he

distributed large estates to his Anglo-Norman cronies who also took over

important positions in the Church. In the Scottish Lowlands he introduced a

feudal system of land ownership, founded on a new, French-speaking Anglo-Norman

aristocracy that remained aloof from the majority of the Gaelic-speaking Celtic

population.

3. Territorial

Expansion and Conflicts with Henry II: At David's death in 1153, the

kingdom of Scotland had been extended to include the Modern English counties of

Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmoreland, territories that were in future to

be held by the kings of Scotland. Alas, the accession of Henry II to the

English throne in 1154 had changed everything.

David

had been succeeded by his grandson, Malcolm IV an eleven-year old boy. He was

no match for the powerful new King of England. At the Treaty of Chester, 1157

Henry's strength, "the authority of his might," forced Malcolm to

give up the northern counties solely in return for the confirmation of his

rights as Earl of Huntingdon. The Scottish border was considerably shifted

northwards. And there it remained until the rash adventures of William,

Malcolm’s brother and successor, got him captured at Alnwich, imprisoned at

Falaise in Normandy, and forced to acknowledge Henry's feudal superiority over

himself and his Scottish kingdom. In addition, to add insult to injury, the

strategic castles of Edinburgh, Stirling, Roxburgh, Jedburgh and Berwick were

to be held by England with English garrisons at Scottish expense.

4. More

Conflicts with Edward I: Edward was ready. He went north to receive homage

from a great number of Scottish nobles as their feudal lord, among them none

other than Robert Bruce, who owned estates in England. Balliol immediately

punished this treachery by seizing Bruce's lands in Scotland and giving them to

his own brother-in-law, John Comyn. Yet within a few months, the Scottish king

was to disappear from the scene. His army was defeated by Edward at Dunbar in

April 1296. Soon after at Brechin, on 10 July, he surrendered his Scottish

throne to the English king, who took into his possession the stone of Scone,

"the coronation stone" of the Scottish kings. At a parliament which

he summoned at Berwick, the English king received homage and the oath of fealty

from over two thousand Scots. He seemed secure in Scotland.

Flushed

with this success, Edward had gone too far. The rising tide of nationalist

fervour in the face of the arrival of the English armies north

of the border created the need for new Scottish leaders. With the killing of an

English sheriff following a brawl with English soldiers in the marketplace at

Lanark, a young Scottish knight, William Wallace found himself at the head of a

fast-spreading movement of national resistance. At Stirling Bridge, a Scottish

force led by Wallace, won an astonishing victory when it completely annihilated

a large, lavishly-equipped English army under the command of Surrey, Edward’s

viceroy.

|

| The battle at Stirling Bridge |

5. Robert

Bruce It was time for Robert Bruce to free himself from his fealty to

Edward and lead the fight for Scotland. At a meeting between the two surviving

claimants for the Scottish throne in Greyfriar's Kirk at Dumfries, Robert Bruce

murdered John Comyn, thus earning the enmity of the many powerful supporters of

the Comyn family, but also excommunication from the Church. His answer was to

strike out boldly, raising the Royal Standard at Scone and, on March 27, 1306,

declaring himself King of Scots. Edward's reply was predictable; he sent a

large army north, defeated Bruce at the battle of Methven, executed many of his

supporters and forced the Scottish king to become a hunted outlaw.

The

indefatigable Scottish leader bided his time. After a year of demoralization

and widespread English terror let loose in Scotland, during which two of his

brothers were killed, Bruce came out of hiding. Aided mightily by his Chief

Lieutenant, Sir James Douglas, "the Black Douglas," he won his first

victory on Palm Sunday, 1307. From all over Scotland, the clans answered the

call and Bruce's forces gathered in strength to fight the English invaders,

winning many encounters against cavalry with his spearmen.

The

aging Edward, the so-called "hammer of the Scots," marched north at

the head of a large army to punish the Scots' impudence; but the now weak and

sick king was ineffectual as a military leader. He could only wish that after

his death his bones would be carried at the head of his army until Scotland had

been crushed. It was left to his son Edward to try to carry out his father's

dying wish. He was no man for the task. Edward II was crowned King of England

in 1307. Faced by too many problems at home and completely lacking the ruthlessness

and resourcefulness of his father, the young king had no wish to get embroiled

in the affairs of Scotland. Bruce was left alone to consolidate his gains and

to punish those who opposed him. In 1311 he drove out the English garrisons in

all their Scottish strongholds except Stirling and invaded northern England.

King Edward finally, begrudgingly, bestirred himself from his dalliances at

Court to respond and took a large army north.

|

| Bruce reviewing troops before the Battle of Bannockburn |

On

Mid-Summer's Day, the 24th of June, 1314 occurred one of the most momentous

battles in British history. The armies of Robert Bruce, heavily outnumbered by

their English rivals, but employing tactics that prevented the English army

from effectively employing its strength, won a decisive victory at Bannockburn.

Scotland was wrenched from English control, its armies free to invade and

harass northern England. Such was Bruce's military successes that he was able

to invade Ireland, where his brother Edward had been crowned King by the

exuberant Irish. A second expedition carried out by Edward II north of the

border was driven back and the English king was forced to seek for peace.

| Battle of Bannockburn 1314 |

The

Declaration of Arboath of 1320 stated that since ancient times the Scots had

been free to choose their own kings, a freedom that was a gift from God. If

Robert Bruce were to prove weak enough to acknowledge Edward as overlord, then

he would be dismissed in favour of someone else. Though English kings still

continued to call themselves rulers of Scotland, just as they called themselves

rulers of France for centuries after being booted out of the continent,

Scotland remained fully independent until 1603 (when James Stuart succeeded

Elizabeth I).

Richard

II (1377-1399) - in Edward III's dotage John of

Gaunt (Ghent, in modern Belgium) was virtual ruler of England. He continued as

regent when Richard II, aged 10, came to the throne in 1377.

Four years later a

poll tax was declared to finance the continuing war with France. Every person

over the age of 15 had to pay one shilling, a large sum in those days. There

was tremendous uproar amongst the peasantry. This, combined with continuing

efforts by land owners to re-introduce servility of the working classes on the

land, led to the Peasant's Revolt. The leaders of the peasants were John Ball,

an itinerant priest, Jack Straw, and Wat Tyler. The revolt is sometimes called

Wat Tyler's Rebellion. They led a mob of up to 100,000 people to London, where

the crowd went on a rampage of destruction, murdered the Archbishop of

Canterbury, and burned John of Gaunt's Savoy Palace.

|

| Richard II |

Richard

II watches Wat Tyler's

death and addresses the peasants in the background

The End of the Revolt. Eventually

they forced a meeting with the young king in a field near Mile End. Things

began amicably enough, but Wat Tyler grew abusive and the Lord Mayor of London

drew his sword and killed him.

At

this point Richard, then only 14, showed great courage, shouting to the

peasants to follow him. He led them off, calmed them down with promises of

reforms, and convinced them to disperse to their homes. His promises were

immediately revoked by his council of advisors, and the leaders of the revolt

were hanged.

Henry IV (1399-1413) - In

1399 Henry Bolingbroke, exiled son of John of Gaunt, landed with an invasion

force while Richard was in Ireland. He defeated Richard in battle, took him

prisoner, and probably had him murdered.

Henry's claim to the throne was poor.

His right to rule was usurpation approved by Parliament and public opinion

Henry IV had a reign notable mainly for a series of rebellions and

invasions in Wales, Scotland, France, and northern England. He was followed by

his son

Henry V (1413-22) - whose short reign was enlivened by attacks on the Lollard heresy which drove it underground at last. He also resurrected claims to the throne of France itself. After spectacular success at the Battle of Agincourt (1415), Henry married Katherine, daughter of the mad Charles VI of France. Henry died young, leaving the nine month old Henry VI (1422-61) to inherit the throne.

.jpg) |

| Henry IV |

Henry V (1413-22) - whose short reign was enlivened by attacks on the Lollard heresy which drove it underground at last. He also resurrected claims to the throne of France itself. After spectacular success at the Battle of Agincourt (1415), Henry married Katherine, daughter of the mad Charles VI of France. Henry died young, leaving the nine month old Henry VI (1422-61) to inherit the throne.

| Crowned King Henry the V |

Henry VI (1422-61) - The

Wars of the Roses and the Princes in the Tower.

Henry

VI was troubled all his life by recurring bouts of madness, during which the

country was ruled by regents. The regents didn't do any better for England than

Henry did, and the long Hundred Years War with France sputtered to an end with

England losing all her possessions in France except for Calais. In England

itself anarchy reigned. Nobles gathered their own private armies and fought for

local supremacy.

|

| Henry VI of England |

John

Ball preaching The Wars of the Roses. The struggle to rule on behalf of an

unfit king was one of the surface reasons for the outbreak of thirty years of

warfare that we now call the Wars of the Roses, fought between the Houses of

York (white rose) and Lancaster (red rose). In reality these squabbles were an

indication of the lawlessness that ran rampant in the land. More squalid than

romantic, the Wars of the Roses decimated both houses in an interminably long,

bloody struggle for the throne. The rose symbols that we name the wars after

were not in general use during the conflict. The House of Lancaster did not

even adopt the red rose as its official symbol until the next century. Henry VI was eventually forced to abdicate in 1461 and died ten years later

in prison, possibly murdered.

Edward IV (1461-1483) - of the house of York who managed to get his dubious claim to the throne legitimized by Parliament.

Edward was the first king to address the House of Commons, but his reign is

notable mostly for the continuing saga of the wars with the House of Lancaster

and unsuccessful wars in France.

Edward V (9 April 1483 until 26 June of the same year) - when Edward died in 1483, his son, Edward V, aged twelve, succeeded him.

In light of his youth, Edward's uncle Richard, Duke

of Gloucester, acted as regent.

The Princes in the Tower. Traditional history, written by later Tudor historians seeking to legitimize their masters' past, has painted Richard as the archetypal wicked uncle. The truth may not be so clear cut. Some things are known, or assumed, to be true. Edward and his younger brother were put in the Tower of London, ostensibly for their own protection.

Richard had the "Princes in the Tower" declared

illegitimate, which may possibly have been true. He then got himself declared

king. He may have been in the right, and certainly England needed a strong and

able king. But he was undone when the princes disappeared and were rumoured to

have been murdered by his orders. In the 17th century workmen repairing a

stairwell at the Tower found the bones of two boys of about the right ages.

Were these the Princes in the Tower, and were they killed by their wicked

uncle? We will probably never know. The person with the most to gain by killing

the princes was not Richard, however, but Henry, Earl of Richmond. Henry also

claimed the throne, seeking "legitimacy" through descent from John of

Gaunt and his mistress.

Richard III (1483–1485) - was King of England from 1483 until his death in 1485, at the age of 32, in the Battle of Bosworth Field. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat at Bosworth Field, the last decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses, marked the end of the Middle Ages in England. He is the subject of the historical play Richard III by William Shakespeare.

Edward IV (1461-1483) - of the house of York who managed to get his dubious claim to the throne legitimized by Parliament.

|

| Edward IV |

Edward V (9 April 1483 until 26 June of the same year) - when Edward died in 1483, his son, Edward V, aged twelve, succeeded him.

|

| Edward V |

The Princes in the Tower. Traditional history, written by later Tudor historians seeking to legitimize their masters' past, has painted Richard as the archetypal wicked uncle. The truth may not be so clear cut. Some things are known, or assumed, to be true. Edward and his younger brother were put in the Tower of London, ostensibly for their own protection.

|

| King Edward V and the Duke of York in the Tower of London by Paul Delaroche. |

Richard III (1483–1485) - was King of England from 1483 until his death in 1485, at the age of 32, in the Battle of Bosworth Field. He was the last king of the House of York and the last of the Plantagenet dynasty. His defeat at Bosworth Field, the last decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses, marked the end of the Middle Ages in England. He is the subject of the historical play Richard III by William Shakespeare.

|

| Late 16th century portrait, housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London. |

When his

brother King Edward IV died

in April 1483, Richard was named Lord Protector of

the realm for Edward's son and successor, the 12-year-old Edward V. As the young king travelled to London from Ludlow, Richard met and

escorted him to lodgings in the Tower of London,

where Edward V's own brother Richard of Shrewsbury joined him shortly afterwards. Arrangements were made for Edward's

coronation on 22 June 1483; but, before the young king could be crowned, his

father's marriage to his mother Elizabeth Woodville was declared invalid, making their

children illegitimate and ineligible for the throne. On 25 June, an assembly of

Lords and commoners endorsed the claims. The following day, Richard III began

his reign, and he was crowned on 6 July 1483. The young princes were not seen

in public after August, and accusations circulated that the boys had been

murdered on Richard's orders, giving rise to the legend of the Princes in the Tower.

Of the two major

rebellions against Richard, the first, in October 1483, was led by staunch

allies of Edward IV and Richard's former ally, Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of

Buckingham; but the

revolt collapsed. In August 1485, Henry Tudor and his uncle, Jasper Tudor,

led a second rebellion against Richard. Henry Tudor landed in southern Wales with a small

contingent of French troops and marched through his birthplace, Pembrokeshire,

recruiting soldiers. Henry's force engaged Richard's army and defeated it at

the Battle of Bosworth Field in Leicestershire.

Richard was struck down in the conflict, making him the last English king to

die in battle on home soil and the first since Harold II was

killed at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

After the

battle Richard's corpse was taken to Leicester and

buried without pomp. His original

tomb monument is believed to have been removed during the Reformation,

and his remains were lost for more than five centuries, believed to have been thrown

into the River Soar. In 2012, an archaeological

excavation was commissioned by the Richard III Society on a city council car park on

the site once occupied by Greyfriars Priory Church. The University of Leicester identified the skeleton found in

the excavation as that of Richard III as a result of radiocarbon dating,

comparison with contemporary reports of his appearance, and comparison of his mitochondrial DNA with

that of two matrilineal descendants of Richard III's eldest sister, Anne of York. Richard's remains were reburied in Leicester Cathedral on

26 March 2015.

The Battle of Bosworth Field. Henry VII defeated and killed Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field (1485), claiming the crown which was found hanging upon a bush, and placing it upon his own head. Bosworth marked the end of the Wars of the Roses. There was no one else left to fight. It also marked the end of the feudal period of English history. With the death of Richard III the crown passed from the Plantagenet line to the new House of Tudor, and a new era of history began.

The Battle of Bosworth Field. Henry VII defeated and killed Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field (1485), claiming the crown which was found hanging upon a bush, and placing it upon his own head. Bosworth marked the end of the Wars of the Roses. There was no one else left to fight. It also marked the end of the feudal period of English history. With the death of Richard III the crown passed from the Plantagenet line to the new House of Tudor, and a new era of history began.

| The Battle of Bosworth Field 1485 |

B. The

Hundred Years War (1336-1453) - in 1337 began the conflict with France known as The

Hundred Years War. Actually, it lasted, on and off, for 116 years, and

despite early successes at Crecy and Poitiers, it was to end with the loss of

virtually all English possessions on the mainland.

The Hundred Years' War was a series

of conflicts waged from 1337 to 1453 by the House of Plantagenet, rulers of the Kingdom of England, against the House of Valois, rulers of

the Kingdom of France, for control

of the latter kingdom. Each side drew many allies into the war. It was one of

the most notable conflicts of the Middle Ages, in which five generations of

kings from two rival dynasties fought for the throne of the largest kingdom in

Western Europe. The war marked both the height of chivalry and its

subsequent decline, and the development of strong national identities in both

countries.

After

the Norman

Conquest, the kings of England were vassals of the kings of France for their possessions in

France. The French kings had endeavored, over the centuries, to reduce these

possessions, to the effect that only Gascony was left

to the English. The confiscation or threat of confiscating this duchy had been

part of French policy to check the growth of English power, particularly

whenever the English were at war with the Kingdom of Scotland, an ally of France.

Through his

mother, Isabella

of France, Edward

III of England was the grandson of Philip IV of France and nephew of Charles

IV of France, the last king of the senior line of the House of Capet. In 1316, a principle was

established denying women succession to the French throne. When Charles IV died

in 1328, Isabella, unable to claim the French throne for herself, claimed it

for her son. The French rejected the claim, maintaining that Isabella could not

transmit a right that she did not possess. For about nine years (1328–1337),

the English had accepted the Valois succession to the French throne. But the

interference of the French king, Philip VI, in Edward III's war against

Scotland led Edward III to reassert his claim to the French throne. Several

overwhelming English victories in the war—especially at Crecy, Poitiers, and Agincourt—raised the

prospects of an ultimate English triumph. However, the greater resources of the

French monarchy precluded a complete conquest. Starting in 1429, decisive

French victories at Patay, Formigny, and Castillon concluded

the war in favor of France, with England permanently losing most of its major

possessions on the continent.

Historians

commonly divide the war into three phases separated by truces:

1. the Edwardian Era War (1337–1360);

2. the Caroline War (1369–1389); and

3. the Lancastrian War (1415–1453).

Contemporary conflicts in neighbouring areas, which were directly related to this conflict, included the War of the Breton Succession (1341–1364), the Castilian Civil War (1366–1369), the War of the Two Peters (1356–1375) in Aragon, and the 1383–85 Crisis in Portugal. Later historians invented the term "Hundred Years' War" as a periodization to encompass all of these events, thus constructing the longest military conflict in history.

1. the Edwardian Era War (1337–1360);

2. the Caroline War (1369–1389); and

3. the Lancastrian War (1415–1453).

Contemporary conflicts in neighbouring areas, which were directly related to this conflict, included the War of the Breton Succession (1341–1364), the Castilian Civil War (1366–1369), the War of the Two Peters (1356–1375) in Aragon, and the 1383–85 Crisis in Portugal. Later historians invented the term "Hundred Years' War" as a periodization to encompass all of these events, thus constructing the longest military conflict in history.

The war owes

its historical significance to multiple factors. By its end, feudal armies had

been largely replaced by professional troops, and aristocratic dominance had

yielded to a democratisation of the manpower and weapons of armies. Although

primarily a dynastic conflict, the war gave impetus to ideas of French and English

nationalism. The wider introduction of weapons and tactics supplanted the

feudal armies where heavy cavalry had dominated.

The war precipitated the creation of the first standing

armies in Western Europe since the time of the Western

Roman Empire, composed largely of commoners and thus helping to

change their role in warfare. With respect to the belligerents, English

political forces over time came to oppose the costly venture. The

dissatisfaction of English nobles, resulting from the loss of their continental

landholdings, became a factor leading to the civil wars known as the Wars of the Roses (1455–1487).

In France, civil wars, deadly epidemics, famines, and bandit free-companies of mercenaries reduced

the population drastically. Shorn of its continental possessions, England was

left with the sense of being an island nation, which profoundly affected its

outlook and development for more than 500 years

Clockwise,

from top left: The Battle of La Rochelle, The Battle of Agincourt, The Battle

of Patay, Joan of Arc at the Siege of Orléans

Parliament's

Power. As is usual in times of war, Parliament grew in power, forcing royal

concessions in return for grants of money. In the early 14th c. the custom

evolved of separate sittings for the Commons (burgesses and knights) and a

Great Council of prelates and magnates. The system of Justices of the Peace,

chosen from among the local nobility, also dates from this time. They became a

sort of amateur body carrying on local administration and government for the

next 500 years.

CAUSES

The Battle for Flanders - Flanders

had grown to be the industrial center of northern Europe and had become

extremely wealthy through its cloth manufacture. It could not produce enough

wool to satisfy its market and imported fine fleece from England. England

depended upon this trade for its foreign exchange. During the 1200's, the

upper-class English had adopted Norman fashions and switched from beer to wine.

The

problem was that England could not grow grapes to produce the wine that many of

the English now favored and had to import it. A triangular trade arose in which

English fleece was exchanged for Flemish cloth, which was then taken to

southern France and exchanged for wine, which was then shipped into England and

Ireland, primarily through the ports of Dublin, Bristol, and London.

But

the counts of Flanders had been vassals of the king of France, and the French

tried to regain control of the region in order to control its wealth. The

English could not permit this, since it would mean that the French monarch would

control their main source of foreign exchange. A civil war soon broke out in

Flanders, with the English supporting the manufacturing middle class and the

French supporting the land-owning nobility.

The Struggle for Control of France - the

English king controlled much of France, particularly in the fertile South.

These lands had come under control of the English when Eleanor of Aquitaine,

heiress to the region, had married Henry II of England in the mid-12th century.

There was constant bickering along the French-English frontier, and the French

kings always had to fear an English invasion from the South. Between Flanders

in the North and the English in the South, they were caught in a

"nutcracker".

The

"Auld Alliance" - the French responded by creating their own

"nutcracker." They allied with the Scots in an arrangement that

persisted well into the 18th century. Thus the English faced the French from

the south and the Scots from the north.

The

Battle for the Channel and North Sea - The French nutcracker would only work if

the French could invade England across the English Channel. (The French call it

"La Manche".) Besides, England could support their Flemish allies

only if they could send aid across the North Sea, and, moreover, English trade

was dependent upon the free flow of naval traffic through the Channel.

Consequently, the French continually tried to gain the upper hand at sea, and

the English constantly resisted them. Both sides commissioned what would have

been pirates if they had not been operating with royal permission to prey upon

each other's shipping, and there were frequent naval clashes in those

constricted waters.

The Dynastic Conflict - the last son of King Philip IV (The

Fair) died in 1328, and the direct male line of the Capetians finally ended

after almost 350 years. Philip had had a daughter, however. This daughter,

Isabelle, had married King Edward II of England, and King Edward III was their

son. He was therefore Philip's grandson and successor in a direct line through

Philip's daughter. The French could not tolerate the idea that Edward might

become King of France, and French lawyers brought up some old Frankish laws,

the so-called Salic Law, which stated that property (including the throne)

could not descend through a female. The French then gave the crown to Philip of

Valois, a nephew of Philip IV. Nevertheless, Edward III had a valid claim to

the throne of France if he wished to pursue it.

An

Aggressive Spirit in England Although France was the most populous country in

Western Europe (20 million inhabitants to England's 4-5 million) and also the

wealthiest, England had a strong central government, many veterans of hard

fighting on England's Welsh and Scottish borders (as well as in Ireland), a

thriving economy, and a popular king. Edward was disposed to fight France, and

his subjects were more than ready to support their young (only 18 years old at

the time) king.

THE

COURSE OF THE WAR - war

broke out in earnest in 1340. The French had assembled a great fleet to support

an army with which they intended to crush all resistance in Flanders. When the

ships had anchored in a dense pack at Sluys in modern Netherlands, the English

attacked and destroyed it with fire ships and victory in a battle fought across

the anchored ships, almost like a land battle on a wooden battlefield. The

English now had control of the Channel and North Sea. They were safe from

French invasion, could attack France at will, and could expect that the war

would be fought on French soil and thus at French expense.

Edward

invaded northern France in 1345. The Black Death had arrived, and his army was

weakened by sickness. As the English force tried to make its way safely to

fortified Channel port, the French attempted to force them into a battle. The

English were finally pinned against the coast by a much superior French army at

a place called Crecy. Edward's army was a combined force: archers, pikemen,

light infantry, and cavalry; the French, by contrast, clung to their

old-fashioned feudal cavalry. The English had archers using the longbow, a weapon

with great penetrating power that could sometimes kill armoured knights, and

often the horses on which they rode. The battle was a disaster for the French.

The English took up position on the crest of a hill, and the French cavalry

tried to ride up the slope to get at their opponents. The long climb up soggy

ground tired and slowed the French horses, giving the English archers and foot

soldiers ample opportunity to wreak havoc in the French ranks. Those few French

who reached the crest of the hill found themselves faced with rude, but

effective, barriers, and, as they tried to withdraw, they were attacked by the

small but fresh English force of mounted knights. Nevertheless, facing much the

same battlefield situation some ten years later, the French employed the same

tactics they had used at Crecy, with the same dismal result, at the battle of

Poiters (1356). The French king and many nobles were captured, and many, many

others were killed. Old fashioned feudal warfare, in which knights fought for

glory, was ended. The first phase of the war ended with a treaty in 1360, but

France continued to suffer. The English had employed mercenaries who, once they

were no longer paid, lived off the country by theft and plunder. Most French

peasants would have found it difficult to distinguish between war and this sort

of peace.

END

OF THE CONFLICT - as

the war dragged on, the English were slowly forced back. They had less French

land to support their war effort as they did so, and the war became more

expensive for them. This caused conflicts at home, such as the Peasants' Revolt

of 1381 and the beginning of civil wars.

Western

Europe in 1382 Nevertheless, in the reign of Henry V, the English took the

offensive once again. At Agincourt, not far from Crecy, the French relapsed

into their old tactics of feudal warfare once again, and were again

disasterously defeated (1415). The English recovered much of the ground they

had lost, and a new peace was based upon Henry's marriage to the French

princess Katherine. These events furnish the plot for Shakespeare's play, Henry

V. With Henry's death in 1422, the war resumed.

In

the following years, the French developed a sense of national identity, as

illustrated by Joan of Arc, a peasant girl who led the French armies to victory

over the English until she was captured and burned by the English as a witch.

The French now had a greater unity, and the French king was able to field

massive armies on much the same model as the British. In addition, however, the

French government began to appreciate the "modern" style of warfare,

and new military commanders began to use guerilla and "small war"

tactics of fighting. The war dragged on for many years. In fact, it was not

until 1565 that the English were forced out of Calais, their last foothold in

continental France, and they still hold the Channel Islands, the last remnant

of England's medieval empire in France.

THE

RESULTS - this

war marked the end of English attempts to control continental territory and the

beginning of its emphasis upon maritime supremacy. By Henry V's marriage into

the House of Valois, an hereditary strain of mental disorder was introduced

into the English royal family. There were great advances in military technology

and science during the period, and the military value of the feudal knight was

thoroughly discredited. The order of knighthood went down fighting, however, in

a wave of civil wars that racked the countries of Western Europe. The European

countries began to establish professional standing armies and to develop the modern

state necessary to maintain such forces.

From

the point of view of the 14th century, however, the most significant result is

that the nobility and secular leaders were busy fighting each other at a time

when the people of Western Europe desperately needed leadership.

House

of Lancaster and Hundred Years' War

(1415–1453)

Henry married

his Plantagenet cousin Mary de Bohun, who was paternally

descended from Edward I and maternally from Edmund Crouchback. They had seven children:

- Edward (1453–1471)

- Thomas (1387–1421)—killed

at the Battle

of Baugé. His marriage to Margaret Holland proved childless; he had an illegitimate son

named John, also known as the Bastard of Clarence.

- John (1389–1435)—had

two childless marriages: to Anne of Burgundy, daughter

of John

the Fearless, and Jacquetta

of Luxembourg. John had an illegitimate son and daughter, named

Richard and Mary, respectively.

- Humphrey (1390–1447)—died

under suspicious circumstances while imprisoned for treason against Henry VI;

his death may have been the result of a stroke.

Parchment Miniature of Henry V's victory at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, from Enguerrand de

Monstrelet's Chronique de France circa 1495

Henry went to

convoluted legal means to justify his succession. Many Lancastrians asserted

that his mother had had legitimate rights through her descent from Edmund Crouchback, who it was

claimed was the elder son of Henry III of England, set aside due to deformity. As the grandson of Lionel

of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, was the heir

presumptive to Richard II and Henry used multiple rationales stressing his

Plantagenet descent, divine grace, powerful friends, and the Richard's

misgovernment. In fact Mortimer never showed interest in the throne. The

later marriage of his granddaughter Anne to Richard's

son consolidated his descendants' claim to the throne with that of the

more junior House of York. Henry

planned to resume war with France, but was plagued with financial problems,

declining health and frequent rebellions. He defeated a Scottish invasion, a serious rebellion by Henry

Percy, 1st Earl of Northumberland in the North and Owain Glyndŵr's rebellion

in Wales. Many saw it as

a punishment from God when Henry was later struck down with unknown but chronic

illnesses.

Henry IV died

in 1413. His son and successor, Henry V of England, aware

that Charles

VI of France's mental illness had caused instability in France,

invaded to assert the Plantagenet claims and won a near total victory over the

French at the Battle

of Agincourt. In

subsequent years Henry recaptured much of Normandy and secured marriage

to Catherine

of Valois. The resulting Treaty of Troyes stated

that Henry's heirs would inherit the throne of France, but conflict continued

with the

Dauphin. When Henry died in 1422, his nine-month-old son succeeded him as Henry

VI of England. During the minority of Henry VI the war caused

political division among his Plantagenet uncles, Bedford, Humphrey of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Gloucester, and Cardinal Beaufort. Humphrey's

wife was accused of treasonable necromancy after

two astrologers in her employ unwisely, if honestly, predicted a serious

illness would endanger Henry VI's life, and Humphrey was later arrested and

died in prison.

Depopulation

stemming from the Black Death led to increased wages, static food costs and a

resulting improvement in the standard of living for the peasantry. However,

under Henry misgovernment and harvest failures depressed the English economy to

a pitiful state known as the Great

Slump. The economy was in ruins by 1450, a consequence of the loss of France,

piracy in the channel and poor trading relations with the Hanseatic League. The economic slowdown began in the 1430s in the

north of the country, spreading south in the 1440s, with the economy not

recovering until the 1480s. It was

also driven by multiple harvest failures in the 1430s and disease amongst

livestock, which drove up the price of food and damaged the wider economy. Certain groups were particularly badly affected:

cloth exports fell by 35 per cent in just four years at the end of the 1440s,

collapsing by up to 90 per cent in some parts of the South-West. The Crown's debts reached £372,000, Henry's

deficit was £20,000 per annum, and tax revenues were half those of his father.

House

of York - Edward III

made his fourth son Edmund the first duke of York in 1385.

Edmund was married to Isabella, a daughter of King Peter of Castile and María

de Padilla and the sister of Constance of Castile, who was the second wife of

Edmund's brother John of Gaunt. Both of Edmund's sons were killed in

1415. Richard became involved in the Southampton Plot, a conspiracy

to depose Henry V in favour of Richard's brother-in-law Edmund Mortimer. When

Mortimer revealed the plot to the king, Richard was executed for treason.

Richard's childless older brother Edward was

killed at the Battle of Agincourt later the same year. Constance of York was Edmund's only daughter and was an ancestor

of Queen Anne Neville. The

increasingly interwoven Plantagenet relationships were demonstrated by Edmund's

second marriage to Joan Holland. Her

sister Alianore

Holland was mother to Richard's wife, Anne Mortimer. Margaret Holland, another of

Joan's sisters, married John

of Gaunt's son. She later married Thomas of Lancaster, John of Gaunt's grandson by

King Henry IV. A third sister, Eleanor

Holland, was mother-in-law to Richard

Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury—John's grandson by his daughter Joan

Beaufort, Countess of Westmorland. These sisters were all granddaughters of Joan of

Kent, the mother of Richard II, and therefore Plantagenet descendants of Edward

I.

Edmund's son

Richard was married to Anne Mortimer, the daughter of Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March and Eleanor

Holland and great-granddaughter of Edward III's second surviving son Lionel.

Anne died giving birth to their only son in September 1411. Richard's execution four years later left two

orphans: Isabel, who married

into the Bourchier family, and a son who was also called Richard. Although his

earldom was forfeited, Richard (the father) was not attainted, and the

four-year-old orphan Richard was his heir. Within months of his father's death,

Richard's childless uncle, Edward Duke of York, was killed at Agincourt.

Richard was allowed to inherit the title of Duke of York in 1426. In 1432 he

acquired the earldoms of March and Ulster on the death of his maternal uncle

Edmund Mortimer, Earl of March, who had died campaigning with Henry V in

France, and the earldom of Cambridge which had belonged to his father. Being

descended from Edward III in both the maternal and the paternal line gave

Richard a significant claim to the throne if the Lancastrian line should fail,

and by cognatic

primogeniture arguably a superior claim. He emphasised the point by being the first to

assume the Plantagenet surname in 1448. Having inherited the March and Ulster

titles, he became the wealthiest and most powerful noble in England, second

only to the king himself. Richard married Cecily Neville, a

granddaughter of John of Gaunt, and had thirteen or possibly fifteen children:

The Battle of Tewkesbury

When Henry VI

had a mental breakdown, Richard was named regent, but the birth of a male heir

resolved the question of succession. When

Henry's sanity returned, the court party reasserted its authority, but Richard

of York and the Nevilles defeated them at a skirmish called the First

Battle of St Albans. The ruling class was deeply shocked and reconciliation

was attempted. York and

the Nevilles fled abroad, but the Nevilles returned to win the Battle

of Northampton, where they captured Henry. When Richard of York joined them he surprised Parliament by claiming

the throne and forcing through the Act

of Accord, which stated that Henry would remain as king for his lifetime, but would

be succeeded by York. Margaret found this disregard for her son's claims

unacceptable, and so the conflict continued. York was killed at the Battle of Wakefield and his head set on display

at Micklegate

Bar along with those of Edmund,

Earl of Rutland, and Richard Neville, Earl of Salisbury, who had been

captured and beheaded. The

Scottish queen Mary of Guelders provided

Margaret with support but London welcomed York's son Edward,

Earl of March and Parliament confirmed that Edward should be

made king. He was crowned after consolidating his position with victory at

the Battle

of Towton.

Edward's

preferment of the former Lancastrian-supporting Woodville family, following his

marriage to Elizabeth

Woodville, led Warwick and Clarence to help Margaret depose Edward and return Henry

to the throne. Edward and Richard,

Duke of Gloucester, fled, but on their return, Clarence switched sides

at the Battle

of Barnet, leading to the death of the Neville brothers. The subsequent Battle

of Tewkesbury brought the demise of the last of the male line

of the Beauforts. The battlefield execution of Edward

of Westminster, Prince of Wales, and the later probable murder of Henry VI

extinguished the House of Lancaster

Medieval

Schools & Universities

Education. There were

many different kinds of schools in medieval England, though few children

received their sometimes dubious benefit. There were small, informal schools

held in the parish church, song schools at cathedrals, almonry schools attached

to monasteries, chantry schools, guild schools, preparatory grammar schools,

and full grammar schools. The curriculum of theses schools was limited to

basics such as learning the alphabet, psalters, and religious rites and lessons

such as the Ten Commandments and the Seven Deadly Sins. The grammar schools

added to this Latin grammar, composition, and translation.

Schools.

In addition to the schools listed above there were also privately endowed

schools like Winchester and Eton. The most famous public school, Eton, was

founded by Henry VI in 1440. The

term "public school" can be misleading. It refers to the fact that

the school drew its students from all over the country rather than just the

local area. In reality "public schools" are anything but public. They

were, and still are, elite boarding schools for the rich or ambitious.

School Life. Most schools

had no books and the students were taught by rote and the skill of individual

masters. Most masters were minor clergy, who themselves were often

indifferently educated. Classes at some of the larger schools could be as large

as 100 or more boys (no girls, though they were accepted at some of the small

local schools), and the school day lasted as long as 13 hours with breaks for

meals. And to top it off students could expect to be beaten regularly with a

birch rod.

Oxford University. Legend has it that Oxford University was founded by King Alfred in 872. A more likely scenario is that it grew out of efforts begun by Alfred to encourage education and establish schools throughout his territory. There may have been a grammar school there in the 9th century. A grammar school was exactly what it sounds like; a place for teaching Latin grammar. The University as we know it actually began in the 12th century (1163) as gatherings of students around popular masters. The university consisted of people, not buildings. The buildings came later as a recognition of something that already existed. In a way, Oxford was never founded; it grew. Cambridge University was founded in 1209 by students fleeing from Oxford after one of the many episodes of violence between the university and the town of Oxford.

Oxford University. Legend has it that Oxford University was founded by King Alfred in 872. A more likely scenario is that it grew out of efforts begun by Alfred to encourage education and establish schools throughout his territory. There may have been a grammar school there in the 9th century. A grammar school was exactly what it sounds like; a place for teaching Latin grammar. The University as we know it actually began in the 12th century (1163) as gatherings of students around popular masters. The university consisted of people, not buildings. The buildings came later as a recognition of something that already existed. In a way, Oxford was never founded; it grew. Cambridge University was founded in 1209 by students fleeing from Oxford after one of the many episodes of violence between the university and the town of Oxford.

Scottish

universities: St. Andrews (1411) and Glasgow (1451) Students. University

students chose their own course of studies, hired their own professors, and

picked their own hours of study. They were free to leave one professor if they

tired of him, and join another, A Norman school about 1130 attending several

lectures before deciding whether to pay him or not. The only books were the

professors, and students wrote notes on parchment or, more commonly, on wax

table

Insecurity of Life in the Middle Ages - the Black Death in England 1348-1350 - in 1347 a Genoese ship from Caffa, on the Black Sea, came ashore at Messina, Sicily. The crew of the ship, what few were left alive, carried with them a deadly cargo, a disease so virulent that it could kill in a matter of hours. It is thought that the disease originated in the Far East, and was spread along major trade routes to Caffa, where Genoa had an established trading post. When it became clear that ships from the East carried the plague, Messina closed its port. The ships were forced to seek safe harbour elsewhere around the Mediterranean, and the disease was able to spread quickly.