For 20 years most Americans remained sure of this confident approach. They accepted the need for a strong stance against the Soviet Union in the Cold War that unfolded after 1945. They endorsed the growth of government authority and accepted the outlines of the rudimentary welfare state first formulated during the New Deal. They enjoyed a postwar prosperity that created new levels of affluence.

But gradually some began to question dominant assumptions. Challenges on a variety of fronts shattered the consensus. In the 1950s, African Americans launched a crusade, joined later by other minority groups and women, for a larger share of the American dream. In the 1960s, politically active students protested the nation’s role abroad, particularly in the corrosive war in Vietnam. A youth counterculture emerged to challenge the status quo. Americans from many walks of life sought to establish a new social and political equilibrium.

1. America in the Cold war

A. Cold war aims - the Cold War was the most important political and diplomatic issue of the early postwar period. It grew out of longstanding disagreements between the Soviet Union and the United States that developed after the Russian Revolution of 1917. The Soviet Communist Party under V.I.Lenin considered itself the spearhead of an international movement that would replace the existing political orders in the West, and indeed throughout the world. In 1918 American troops participated in the Allied intervention in Russia on behalf of anti-Bolshevik forces. American diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union did not come until 1933. Even then, suspicions persisted. During World War II, however, the two countries found themselves allied and downplayed their differences to counter the Nazi threat.

At the war’s end, antagonisms surfaced again. The United States hoped to share with other countries its conception of liberty, equality, and democracy. It sought also to learn from the perceived mistakes of the post-WWI era, when American political disengagement and economic protectionism were thought to have contributed to the rise of dictatorships in Europe and elsewhere. Faced again with a postwar world of civil wars and disintegrating empires, the nation hoped to provide the stability to make peaceful reconstruction possible. Recalling the specter of the Great Depression (1929-40), America now advocated open trade for two reasons: to create markets for American agricultural and industrial products, and to ensure the ability of Western European nations to export as a means of rebuilding their economies. Reduced trade barriers, American policy makers believed, would promote economic growth at home and abroad, bolstering U.S. friends and allies in the process.

The Soviet Union had its own

agenda - the Russian historical tradition of centralized, autocratic government

contrasted with the American emphasis on democracy. Marxist-Leninist ideology

had been downplayed during the war but still guided Soviet policy. Devastated by

the struggle in which 20 million Soviet citizens had died, the Soviet Union was

intent on rebuilding and on protecting itself from another such terrible

conflict. The Soviets were particularly concerned about another invasion of

their territory from the west. Having repelled Hitler’s thrust, they were

determined to preclude another such attack. They demanded “defensible” borders

and “friendly” regimes in Eastern Europe and seemingly equated both with the

spread of Communism, regardless of the wishes of native populations. However,

the United States had declared that one of its war aims was the restoration of

independence and self-government to Poland, Czechoslovakia, and the other

countries of Central and Eastern Europe.

B. The beginning of the Cold war - the nation’s new chief executive,

Harry S.Truman, succeeded Franklin D.Roosevelt as president before the end of

the war. An unpretentious man who had previously served as Democratic senator

from Missouri, then as vice president, Truman initially felt ill-prepared to

govern. Roosevelt had not discussed complex postwar issues with him, and he had

little experience in international affairs. “I’m not big enough for this job,”

he told a former colleague.

Still, Truman responded quickly to new

challenges. Sometimes impulsive on small matters, he proved willing to make

hard and carefully considered decisions on large ones. A small sign on his White

House desk declared, “The Buck Stops Here.” His judgments about how to respond

to the Soviet Union ultimately determined the shape of the early Cold War.

ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR - the Cold War developed as differences about the shape of the postwar world created suspicion and distrust between the United States and the Soviet Union. The first — and most difficult — test case was Poland, the eastern half of which had been invaded and occupied by the USSR in 1939. Moscow demanded a government subject to Soviet influence; Washington wanted a more independent, representative govern following the Western model. The Yalta Conference of February 1945 had produced an agreement on Eastern Europe open to different interpretations. It included a promise of “free and unfettered” elections.

Meeting with Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov less than two weeks after becoming president, Truman stood firm on Polish self-determination, lecturing the Soviet diplomat about the need to implement the Yalta accords. When Molotov protested, “I have never been talked to like that in my life,” Truman retorted, “Carry out your agreements and you won’t get talked to like that.” Relations deteriorated from that point onward.

ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR - the Cold War developed as differences about the shape of the postwar world created suspicion and distrust between the United States and the Soviet Union. The first — and most difficult — test case was Poland, the eastern half of which had been invaded and occupied by the USSR in 1939. Moscow demanded a government subject to Soviet influence; Washington wanted a more independent, representative govern following the Western model. The Yalta Conference of February 1945 had produced an agreement on Eastern Europe open to different interpretations. It included a promise of “free and unfettered” elections.

Meeting with Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov less than two weeks after becoming president, Truman stood firm on Polish self-determination, lecturing the Soviet diplomat about the need to implement the Yalta accords. When Molotov protested, “I have never been talked to like that in my life,” Truman retorted, “Carry out your agreements and you won’t get talked to like that.” Relations deteriorated from that point onward.

During the closing months of World War

II, Soviet military forces occupied all of Central and Eastern Europe. Moscow

used its military power to support the efforts of the Communist parties in

Eastern Europe and crush the democratic parties. Communists took over one

nation after another. The process concluded with a shocking coup d’etat in

Czechoslovakia in 1948.

Public statements defined the beginning of the Cold War. In 1946 Stalin declared that international peace was impossible “under the present capitalist development of the world economy.” Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered a dramatic speech in Fulton, Missouri, with Truman sitting on the platform. “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic,” Churchill said, “an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.” Britain and the United States, he declared, had to work together to counter the Soviet threat.

CONTAINMENT - containment of the Soviet Union became American policy in the postwar years. George Kennan, a top official at the U.S. embassy in Moscow, defined the new approach in the Long Telegram he sent to the State Department in 1946. He extended his analysis in an article under the signature “X” in the prestigious journal Foreign Affairs. Pointing to Russia’s traditional sense of insecurity, Kennan argued that the Soviet Union would not soften its stance under any circumstances. Moscow, he wrote, was “committed fanatically to the belief that with the United States there can be no permanent modus vivendi, that it is desirable and necessary that the internal harmony of our society be disrupted.” Moscow’s pressure to expand its power had to be stopped through “firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies....”

The first significant application of the containment doctrine came in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean. In early 1946, the United States demanded, and obtained, a full Soviet withdrawal from Iran, the northern half of which it had occupied during the war. That summer, the United States pointedly supported Turkey against Soviet demands for control of the Turkish straits between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. In early 1947, American policy crystallized when Britain told the United States that it could no longer afford to support the government of Greece against a strong Communist insurgency.

The Truman Doctrine - In a strongly worded speech to Congress, Truman declared, “I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” Journalists quickly dubbed this statement the “Truman Doctrine.” The president asked Congress to provide $400 million for economic and military aid, mostly to Greece but also to Turkey. After an emotional debate that resembled the one between interventionists and isolationists before World War II, the money was appropriated.

Critics from the left later charged that to whip up American support for the policy of containment, Truman overstated the Soviet threat to the United States. In turn, his statements inspired a wave of hysterical anti-Communism throughout the country. Perhaps so. Others, however, would counter that this argument ignores the backlash that likely would have occurred if Greece, Turkey, and other countries had fallen within the Soviet orbit with no opposition from the United States.

Marshal plan - Containment also called for extensive economic aid to assist the recovery of war-torn Western Europe. With many of the region’s nations economically and politically unstable, the United States feared that local Communist parties, directed by Moscow, would capitalize on their wartime record of resistance to the Nazis and come to power. “The patient is sinking while the doctors deliberate,” declared Secretary of State George C.Marshall. In mid-1947 Marshall asked troubled European nations to draw up a program “directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos.”

Public statements defined the beginning of the Cold War. In 1946 Stalin declared that international peace was impossible “under the present capitalist development of the world economy.” Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered a dramatic speech in Fulton, Missouri, with Truman sitting on the platform. “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic,” Churchill said, “an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.” Britain and the United States, he declared, had to work together to counter the Soviet threat.

CONTAINMENT - containment of the Soviet Union became American policy in the postwar years. George Kennan, a top official at the U.S. embassy in Moscow, defined the new approach in the Long Telegram he sent to the State Department in 1946. He extended his analysis in an article under the signature “X” in the prestigious journal Foreign Affairs. Pointing to Russia’s traditional sense of insecurity, Kennan argued that the Soviet Union would not soften its stance under any circumstances. Moscow, he wrote, was “committed fanatically to the belief that with the United States there can be no permanent modus vivendi, that it is desirable and necessary that the internal harmony of our society be disrupted.” Moscow’s pressure to expand its power had to be stopped through “firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies....”

The first significant application of the containment doctrine came in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean. In early 1946, the United States demanded, and obtained, a full Soviet withdrawal from Iran, the northern half of which it had occupied during the war. That summer, the United States pointedly supported Turkey against Soviet demands for control of the Turkish straits between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. In early 1947, American policy crystallized when Britain told the United States that it could no longer afford to support the government of Greece against a strong Communist insurgency.

The Truman Doctrine - In a strongly worded speech to Congress, Truman declared, “I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” Journalists quickly dubbed this statement the “Truman Doctrine.” The president asked Congress to provide $400 million for economic and military aid, mostly to Greece but also to Turkey. After an emotional debate that resembled the one between interventionists and isolationists before World War II, the money was appropriated.

Critics from the left later charged that to whip up American support for the policy of containment, Truman overstated the Soviet threat to the United States. In turn, his statements inspired a wave of hysterical anti-Communism throughout the country. Perhaps so. Others, however, would counter that this argument ignores the backlash that likely would have occurred if Greece, Turkey, and other countries had fallen within the Soviet orbit with no opposition from the United States.

Marshal plan - Containment also called for extensive economic aid to assist the recovery of war-torn Western Europe. With many of the region’s nations economically and politically unstable, the United States feared that local Communist parties, directed by Moscow, would capitalize on their wartime record of resistance to the Nazis and come to power. “The patient is sinking while the doctors deliberate,” declared Secretary of State George C.Marshall. In mid-1947 Marshall asked troubled European nations to draw up a program “directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos.”

The Soviets participated in the first

planning meeting, then departed rather than share economic data and submit to

Western controls on the expenditure of the aid. The remaining 16 nations

hammered out a request that finally came to $17,000 million for a four-year

period. In early 1948 Congress voted to fund the “Marshall Plan,” which helped

underwrite the economic resurgence of Western Europe. It is generally regarded

as one of the most successful foreign policy initiatives in U.S.history.

Postwar Germany was a special problem. It had been divided into U.S., Soviet, British, and French zones of occupation, with the former German capital of Berlin (itself divided into four zones), near the center of the Soviet zone. When the Western powers announced their intention to create a consolidated federal state from their zones, Stalin responded. On June 24, 1948, Soviet forces blockaded Berlin, cutting off all road and rail access from the West. American leaders feared that losing Berlin would be a prelude to losing Germany and subsequently all of Europe. Therefore, in a successful demonstration of Western resolve known as the Berlin Airlift, Allied air forces took to the sky, flying supplies into Berlin. U.S., French, and British planes delivered nearly 2,250,000 tons of goods, including food and coal. Stalin lifted the blockade after 231 days and 277,264 flights.

Postwar Germany was a special problem. It had been divided into U.S., Soviet, British, and French zones of occupation, with the former German capital of Berlin (itself divided into four zones), near the center of the Soviet zone. When the Western powers announced their intention to create a consolidated federal state from their zones, Stalin responded. On June 24, 1948, Soviet forces blockaded Berlin, cutting off all road and rail access from the West. American leaders feared that losing Berlin would be a prelude to losing Germany and subsequently all of Europe. Therefore, in a successful demonstration of Western resolve known as the Berlin Airlift, Allied air forces took to the sky, flying supplies into Berlin. U.S., French, and British planes delivered nearly 2,250,000 tons of goods, including food and coal. Stalin lifted the blockade after 231 days and 277,264 flights.

NATO - By then, Soviet domination of Eastern

Europe, and especially the Czech coup, had alarmed the Western Europeans. The

result, initiated by the Europeans, was a military alliance to complement

economic efforts at containment. The Norwegian historian Geir Lundestad has called

it “empire by invitation.” In 1949 the United States and 11 other countries

established the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). An attack against

one was to be considered an attack against all, to be met by appropriate

force. NATO was the first peacetime “entangling alliance” with powers outside

the Western hemisphere in American history.

The next year, the United States

defined its defense aims clearly. The National Security Council (NSC) — the

forum where the President, Cabinet officers, and other executive branch

members consider national security and foreign affairs issues — undertook a

full-fledged review of American foreign and defense policy. The resulting document,

known as NSC-68, signaled a new direction in American security “the Soviet Union was engaged in a

fanatical effort to seize control of all governments wherever possible,” the

document committed America to assist allied nations anywhere in the world that

seemed threatened by Soviet aggression. After the start of the Korean War, a

reluctant Truman approved the document. The United States proceeded to increase

defense spending dramatically.

THE COLD WAR IN ASIA AND THE MIDDLE

EAST - while seeking to prevent Communist

ideology from gaining further adherents in Europe, the United States also

responded to challenges elsewhere.

In 1949, the communist leader Mao Zedong won control of mainland China in a civil war, proclaimed the People's Republic of China, then traveled to Moscow where he negotiated the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship. China had thus moved from a close ally of the U.S. to a bitter enemy, and the two fought each other starting in late 1950 in Korea. The Truman administration responded with a secret 1950 plan, NSC-68, designed to confront the Communists with large-scale defense spending. The Russians had built an atomic bomb by 1950—much sooner than expected; Truman ordered the development of the hydrogen bomb. Two of the spies who gave atomic secrets to Russia were tried and executed.

France was hard-pressed by Communist insurgents in the First Indochina War. The U.S. in 1950 started to fund the French effort on the proviso that the Vietnamese be given more autonomy.

In China, Americans worried about the advances of Mao Zedong and his Communist Party. During World War II, the Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communist forces waged a civil war even as they fought the Japanese. Chiang had been a war-time ally, but his government was hopelessly inefficient and corrupt. American policy makers had little hope of saving his regime and considered Europe vastly more important. With most American aid moving across the Atlantic, Mao’s forces seized power in 1949. Chiang’s government fled to the island of Taiwan. When China’s new ruler announced that he would support the Soviet Union against the “imperialist” United States, it appeared that Communism was spreading out of control, at least in Asia.

In 1949, the communist leader Mao Zedong won control of mainland China in a civil war, proclaimed the People's Republic of China, then traveled to Moscow where he negotiated the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship. China had thus moved from a close ally of the U.S. to a bitter enemy, and the two fought each other starting in late 1950 in Korea. The Truman administration responded with a secret 1950 plan, NSC-68, designed to confront the Communists with large-scale defense spending. The Russians had built an atomic bomb by 1950—much sooner than expected; Truman ordered the development of the hydrogen bomb. Two of the spies who gave atomic secrets to Russia were tried and executed.

France was hard-pressed by Communist insurgents in the First Indochina War. The U.S. in 1950 started to fund the French effort on the proviso that the Vietnamese be given more autonomy.

In China, Americans worried about the advances of Mao Zedong and his Communist Party. During World War II, the Nationalist government under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communist forces waged a civil war even as they fought the Japanese. Chiang had been a war-time ally, but his government was hopelessly inefficient and corrupt. American policy makers had little hope of saving his regime and considered Europe vastly more important. With most American aid moving across the Atlantic, Mao’s forces seized power in 1949. Chiang’s government fled to the island of Taiwan. When China’s new ruler announced that he would support the Soviet Union against the “imperialist” United States, it appeared that Communism was spreading out of control, at least in Asia.

The Korean War - brought armed conflict

between the United States and China. The

United States and the Soviet Union had divided Korea along the 38th parallel

after liberating it from Japan at the end of World War II.Originally a matter

of military convenience, the dividing line became more rigid as both major

powers set up governments in their respective occupation zones and continued to

support them even after departing.

Stalin approved a North Korean plan to invade U.S.-supported South Korea in June 1950. President Truman immediately and unexpectedly implemented the containment policy by a full-scale commitment of American and UN forces to Korea. He did not consult or gain approval of Congress but did gain the approval of the United Nations (UN) to drive back the North Koreans and re-unite that country in terms of a rollback strategy.

After a few weeks of retreat, General Douglas MacArthur's success at the Battle of Inchon turned the war around; UN forces invaded North Korea. This advantage was lost when hundreds of thousands of Chinese entered an undeclared war against the United States and pushed the US/UN/Korean forces back to the original starting line, the 38th parallel. The war became a stalemate, with over 33,000 American dead and 100,000 wounded but nothing to show for it except a resolve to continue the containment policy. Truman fired MacArthur but was unable to end the war. Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952 campaigned against Truman's failures of "Korea, Communism and Corruption," promising to go to Korea himself and end the war. By threatening to use nuclear weapons in 1953, Eisenhower ended the war with a truce that is still in effect.

Stalin approved a North Korean plan to invade U.S.-supported South Korea in June 1950. President Truman immediately and unexpectedly implemented the containment policy by a full-scale commitment of American and UN forces to Korea. He did not consult or gain approval of Congress but did gain the approval of the United Nations (UN) to drive back the North Koreans and re-unite that country in terms of a rollback strategy.

After a few weeks of retreat, General Douglas MacArthur's success at the Battle of Inchon turned the war around; UN forces invaded North Korea. This advantage was lost when hundreds of thousands of Chinese entered an undeclared war against the United States and pushed the US/UN/Korean forces back to the original starting line, the 38th parallel. The war became a stalemate, with over 33,000 American dead and 100,000 wounded but nothing to show for it except a resolve to continue the containment policy. Truman fired MacArthur but was unable to end the war. Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952 campaigned against Truman's failures of "Korea, Communism and Corruption," promising to go to Korea himself and end the war. By threatening to use nuclear weapons in 1953, Eisenhower ended the war with a truce that is still in effect.

In June 1950, after consultations with

and having obtained the assent of the Soviet Union, North Korean leader Kim

Il-sung dispatched his Soviet-supplied army across the 38th parallel and

attacked southward, overrunning Seoul. Truman,

perceiving the North Koreans as Soviet pawns in the global struggle, readied

American forces and ordered World War II hero General Douglas MacArthur to

Korea. Meanwhile, the United States was able to secure a U.N. resolution branding

North Korea as an aggressor. (The

Soviet Union, which could have vetoed any action had it been occupying its seat

on the Security Council, was boycotting the United Nations to protest a

decision not to admit Mao’s new Chinese regime.)

The war seesawed back and forth. U.S.and Korean forces were initially pushed into an enclave far to the south around the city of Pusan. A daring amphibious landing at Inchon, the port for the city of Seoul, drove the North Koreans back and threatened to occupy the entire peninsula. In November, China entered the war, sending massive forces across the Yalu River. U.N. forces, largely American, retreated once again in bitter fighting. Commanded by General Matthew B.Ridgway, they stopped the overextended Chinese, and slowly fought their way back to the 38th parallel. MacArthur meanwhile challenged Truman’s authority by attempting to orchestrate public support for bombing China and assisting an invasion of the mainland by Chiang Kai-shek’s forces. In April 1951, Truman relieved him of his duties and replaced him with Ridgway.

The Cold War stakes were high. Mindful of the European priority, the U.S.government decided against sending more troops to Korea and was ready to settle for the prewar status quo. The result was frustration among many Americans who could not understand the need for restraint. Truman’s popularity plunged to a 24-percent approval rating, the lowest to that time of any president since pollsters had begun to measure presidential popularity. Truce talks began in July 1951. The two sides finally reached an agreement in July 1953, during the first term of Truman’s successor, Dwight Eisenhower.

Cold War struggles also occurred in the Middle East.The region’s strategic importance as a supplier of oil had provided much of the impetus for pushing the Soviets out of Iran in 1946. But two years later, the United States officially recognized the new state of Israel 15 minutes after it was proclaimed — a decision Truman made over strong resistance from Marshall and the State Department. The result was an enduring dilemma — how to maintain ties with Israel while keeping good relations with bitterly anti-Israeli (and oil-rich) Arab states.

C. The Cold War at home - not only did the Cold War shape U.S. foreign policy, it also had a profound effect on domestic affairs. Americans had long feared radical subversion. These fears could at times be overdrawn, and used to justify otherwise unacceptable political restrictions, but it also was true that individuals under Communist Party discipline and many “fellow traveler” hangers-on gave their political allegiance not to the United States, but to the international Communist movement, or, practically speaking, to Moscow. During the Red Scare of 1919-1920, the government had attempted to remove perceived threats to American society. After World War II, it made strong efforts against Communism within the United States. Foreign events, espionage scandals, and politics created an anti-Communist hysteria.

The war seesawed back and forth. U.S.and Korean forces were initially pushed into an enclave far to the south around the city of Pusan. A daring amphibious landing at Inchon, the port for the city of Seoul, drove the North Koreans back and threatened to occupy the entire peninsula. In November, China entered the war, sending massive forces across the Yalu River. U.N. forces, largely American, retreated once again in bitter fighting. Commanded by General Matthew B.Ridgway, they stopped the overextended Chinese, and slowly fought their way back to the 38th parallel. MacArthur meanwhile challenged Truman’s authority by attempting to orchestrate public support for bombing China and assisting an invasion of the mainland by Chiang Kai-shek’s forces. In April 1951, Truman relieved him of his duties and replaced him with Ridgway.

The Cold War stakes were high. Mindful of the European priority, the U.S.government decided against sending more troops to Korea and was ready to settle for the prewar status quo. The result was frustration among many Americans who could not understand the need for restraint. Truman’s popularity plunged to a 24-percent approval rating, the lowest to that time of any president since pollsters had begun to measure presidential popularity. Truce talks began in July 1951. The two sides finally reached an agreement in July 1953, during the first term of Truman’s successor, Dwight Eisenhower.

Cold War struggles also occurred in the Middle East.The region’s strategic importance as a supplier of oil had provided much of the impetus for pushing the Soviets out of Iran in 1946. But two years later, the United States officially recognized the new state of Israel 15 minutes after it was proclaimed — a decision Truman made over strong resistance from Marshall and the State Department. The result was an enduring dilemma — how to maintain ties with Israel while keeping good relations with bitterly anti-Israeli (and oil-rich) Arab states.

C. The Cold War at home - not only did the Cold War shape U.S. foreign policy, it also had a profound effect on domestic affairs. Americans had long feared radical subversion. These fears could at times be overdrawn, and used to justify otherwise unacceptable political restrictions, but it also was true that individuals under Communist Party discipline and many “fellow traveler” hangers-on gave their political allegiance not to the United States, but to the international Communist movement, or, practically speaking, to Moscow. During the Red Scare of 1919-1920, the government had attempted to remove perceived threats to American society. After World War II, it made strong efforts against Communism within the United States. Foreign events, espionage scandals, and politics created an anti-Communist hysteria.

When Republicans were victorious in the midterm congressional elections of 1946 and appeared ready to investigate subversive activity, President Truman established a Federal Employee Loyalty Program. It had little impact on the lives of most civil servants, but a few hundred were dismissed, some unfairly.

In 1947 the House Committee on Un-American Activities investigated the motion-picture industry to determine whether Communist sentiments were being reflected in popular films. When some writers (who happened to be secret members of the Communist Party) refused to testify, they were cited for contempt and sent to prison. After that, the film companies refused to hire anyone with a marginally questionable past.

In 1948, Alger Hiss, who had been an assistant secretary of state and an adviser to Roosevelt at Yalta, was publicly accused of being a Communist spy by Whittaker Chambers, a former Soviet agent. Hiss denied the accusation, but in 1950 he was convicted of perjury. Subsequent evidence indicates that he was indeed guilty.

In 1949 the Soviet Union shocked Americans by testing its own atomic bomb. In 1950, the government uncovered a British-American spy network that transferred to the Soviet Union materials about the development of the atomic bomb. Two of its operatives, Julius Rosenberg and his wife Ethel, were sentenced to death.

|

| Julius Rosenberg and his wife Ethel |

Anti-Communism and McCarthyism: 1947–54 - the most vigorous anti-Communist warrior was Senator Joseph R.McCarthy, a Republican from Wisconsin. He gained national attention in 1950 by claiming that he had a list of 205 known Communists in the State Department. Though McCarthy subsequently changed this figure several times and failed to substantiate any of his charges, he struck a responsive public chord.

McCarthy gained power when the Republican Party won control of the Senate in 1952. As a committee chairman, he now had a forum for his crusade. Relying on extensive press and television coverage, he continued to search for treachery among second-level officials in the Eisenhower administration. Enjoying the role of a tough guy doing dirty but necessary work, he pursued presumed Communists with vigor.

McCarthy overstepped himself by challenging the U.S. Army when one of his assistants was drafted. Television brought the hearings into millions of homes. Many Americans saw McCarthy’s savage tactics for the first time, and public support began to wane. The Republican Party, which had found McCarthy useful in challenging a Democratic administration when Truman was president, began to see him as an embarrassment. The Senate finally condemned him for his conduct.

McCarthy in many ways represented the worst domestic excesses of the Cold War. As Americans repudiated him, it became natural for many to assume that the Communist threat at home and abroad had been grossly overblown. As the country moved into the 1960s, anti-Communism became increasingly suspect, especially among intellectuals and opinion-shapers.

In 1947, well before McCarthy became active, the Conservative Coalition in Congress passed the Taft Hartley Act, designed to balance the rights of management and unions, and delegitimizing Communist union leaders. The challenge of rooting out Communists from labor unions and the Democratic Party was successfully undertaken by liberals, such as Walter Reuther of the autoworkers union and Ronald Reagan of the Screen Actors Guild (Reagan was a liberal Democrat at the time). Many of the purged leftists joined the presidential campaign in 1948 of FDR's Vice President Henry A. Wallace.

With anxiety over Communism in Korea and China

reaching fever pitch in 1950, a previously obscure Senator, Joe McCarthy of Wisconsin, launched Congressional

investigations into the cover-up of spies in the government. McCarthy dominated

the media, and used reckless allegations and tactics that allowed his opponents

to effectively counterattack. Irish Catholics (including conservative

wunderkind William F. Buckley, Jr. and

the Kennedy Family) were

intensely anti-Communist and defended McCarthy (a fellow Irish Catholic). Paterfamilias Joseph Kennedy (1888–1969), a very active

conservative Democrat, was McCarthy's most ardent supporter and got his

son Robert F. Kennedy a

job with McCarthy. McCarthy had talked of "twenty years of treason"

(i.e. since Roosevelt's election in 1932). When, in 1953, he started talking of

"21 years of treason" and launched a major attack on the Army for

promoting a Communist dentist in the medical corps, his recklessness proved too

much for Eisenhower, who encouraged Republicans to censure McCarthy formally in

1954. The Senator's power collapsed overnight. Senator John F. Kennedy did not vote for

censure. Buckley went on to found the National Review in 1955 as a weekly magazine

that helped define

the conservative position on public issues.

"McCarthyism" was expanded to include attacks on supposed Communist influence in Hollywood, which resulted in a black-list whereby artists who refused to testify about possible Communist connections could not get work. Some famous celebrities (such as Charlie Chaplin) left the U.S.; other worked under pseudonyms (such as Dalton Trumbo). McCarthyism included investigations into academics and teachers as well.

"McCarthyism" was expanded to include attacks on supposed Communist influence in Hollywood, which resulted in a black-list whereby artists who refused to testify about possible Communist connections could not get work. Some famous celebrities (such as Charlie Chaplin) left the U.S.; other worked under pseudonyms (such as Dalton Trumbo). McCarthyism included investigations into academics and teachers as well.

2. America in 1950s

A. The Affluent society

THE POSTWAR ECONOMY: 1945-1960 - in the decade and a half after World War II, the United States experienced phenomenal economic growth and consolidated its position as the world’s richest country. Gross national product (GNP), a measure of all goods and services produced in the United States, jumped from about $200,000-million in 1940 to $300,000-million in 1950 to more than $500,000-million in 1960. More and more Americans now considered themselves part of the middle class - 60 %.

The growth had different sources. The economic stimulus provided by large-scale public spending for World War II helped get it started. Two basic middle-class needs did much to keep it going. The number of automobiles produced annually quadrupled between 1946 and 1955. A housing boom, stimulated in part by easily affordable mortgages for returning servicemen, fueled the expansion. The rise in defense spending as the Cold War escalated also played a part.

After 1945 the major corporations in America grew even larger. There had been earlier waves of mergers in the 1890s and in the 1920s; in the 1950s another wave occurred. Franchise operations like McDonald’s fast-food restaurants allowed small entrepreneurs to make themselves part of large, efficient enterprises. Big American corporations also developed holdings overseas, where labor costs were often lower.

Workers found their own lives changing as industrial America changed. Fewer workers produced goods; more provided services. As early as 1956 a majority of employees held white-collar jobs, working as managers, teachers, salespersons, and office operatives. Some firms granted a guaranteed annual wage, long-term employment contracts, and other benefits. With such changes, labor militancy was undermined and some class distinctions began to fade.

Cities - the West and the Southwest grew with increasing rapidity, a trend that would continue through the end of the century. Sun Belt cities like Houston, Texas; Miami, Florida; Albuquerque, New Mexico; and Phoenix, Arizona, expanded rapidly. Los Angeles, California, moved ahead of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as the third largest U.S.city and then surpassed Chicago, metropolis of the Midwest. The 1970 census showed that California had displaced New York as the nation’s largest state. By 2000, Texas had moved ahead of New York into second place.

Wartime rationing was officially lifted in September 1945, but prosperity did not immediately return as the next three years would witness the difficult transition back to a peacetime economy. 12 million returning veterans were in need of work and in many cases could not find it. Inflation became a rather serious problem, averaging over 10% a year until 1950 and raw materials shortages dogged manufacturing industry. In addition, labor strikes rocked the nation, in some cases exacerbated by racial tensions due to African-Americans having taken jobs during the war and now being faced with irate returning veterans who demanded that they step aside. The huge number of women employed in the workforce in the war were also rapidly cleared out make room for their husbands. Following the Republican takeover of Congress in the 1946 elections, President Truman was compelled to reduce taxes and curb government interference in the economy. With this done, the stage was set for the economic boom that, with only a few minor hiccups, would last for the next 23 years. After the initial hurdles of the 1945-48 period were overcome, Americans found themselves flush with cash from wartime work due to there being little to buy for several years. The result was a mass consumer spending spree, with a huge and voracious demand for new homes, cars, and housewares. Increasing numbers enjoyed high wages, larger houses, better schools, more cars and home comforts like vacuum cleaners, washing machines—which were all made for labor-saving and to make housework easier. Inventions familiar in the early 21st century made their first appearance during this era. The live-in maid and cook, common features of middle-class homes at the beginning of the century, were virtually unheard of in the 1950s; only the very rich had servants. Householders enjoyed centrally heated homes with running hot water. New style furniture was bright, cheap, and light, and easy to move around. As noted by John Kenneth Galbraith in 1958:

"the ordinary individual has access to amenities

– foods, entertainments, personal transportation, and plumbing – in which not

even the rich rejoiced a century ago."

Suburbs - an even more important form of movement led Americans out of inner cities into new suburbs, where they hoped to find affordable housing for the larger families spawned by the postwar baby boom.

With Detroit turning out automobiles as fast as possible, city dwellers gave up cramped apartments for a suburban life style centered around children and housewives, with the male breadwinner commuting to work. Suburbia encompassed a third of the nation's population by 1960. The growth of suburbs was not only a result of postwar prosperity, but innovations of the single-family housing market with low interest rates on 20 and 30 year mortgages, and low down payments, especially for veterans. William Levitt began a national trend with his use of mass-production techniques to construct a large "Levittown" housing development on Long Island. Meanwhile, the suburban population swelled because of the baby boom. Suburbs provided larger homes for larger families, security from urban living, privacy, and space for consumer goods.

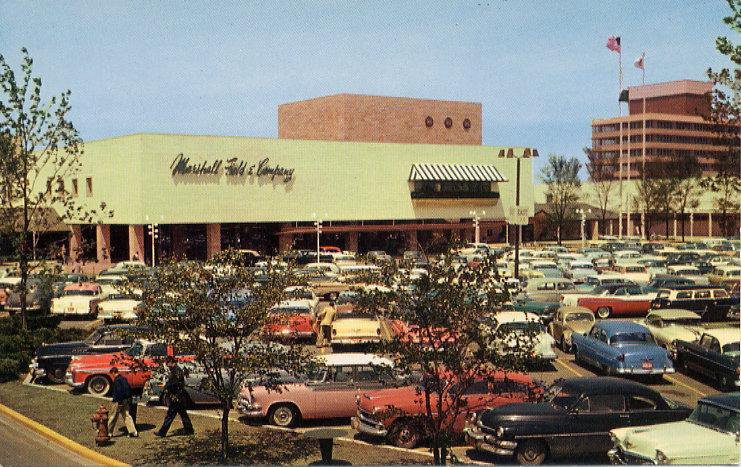

As suburbs grew, businesses moved into the new areas. Large shopping centers containing a great variety of stores changed consumer patterns. The number of these centers rose from eight at the end of World War II to 3,840 in 1960. With easy parking and convenient evening hours, customers could avoid city shopping entirely. An unfortunate by-product was the “hollowing-out” of formerly busy urban cores.

Suburbs - an even more important form of movement led Americans out of inner cities into new suburbs, where they hoped to find affordable housing for the larger families spawned by the postwar baby boom.

With Detroit turning out automobiles as fast as possible, city dwellers gave up cramped apartments for a suburban life style centered around children and housewives, with the male breadwinner commuting to work. Suburbia encompassed a third of the nation's population by 1960. The growth of suburbs was not only a result of postwar prosperity, but innovations of the single-family housing market with low interest rates on 20 and 30 year mortgages, and low down payments, especially for veterans. William Levitt began a national trend with his use of mass-production techniques to construct a large "Levittown" housing development on Long Island. Meanwhile, the suburban population swelled because of the baby boom. Suburbs provided larger homes for larger families, security from urban living, privacy, and space for consumer goods.

Developers like William J. Levitt built new communities — with homes that all looked alike — using the techniques of mass production. Levitt’s houses were prefabricated — partly assembled in a factory rather than on the final location — and modest, but Levitt’s methods cut costs and allowed new owners to possess a part of the American dream.

As suburbs grew, businesses moved into the new areas. Large shopping centers containing a great variety of stores changed consumer patterns. The number of these centers rose from eight at the end of World War II to 3,840 in 1960. With easy parking and convenient evening hours, customers could avoid city shopping entirely. An unfortunate by-product was the “hollowing-out” of formerly busy urban cores.

|

| mission valley shopping center |

|

| Old Orchard Shopping Center. Skokie, Illinois - 1950's |

New highways created better access to the suburbs and its shops. The Highway Act of 1956 provided $26,000-million, the largest public works expenditure in U.S.history, to build more than 64,000 kilometers of limited access interstate highways to link the country together.

Consumerism - represented one of the consequences (as

well as one of the key ingredients) of the postwar economic boom. The initial quest

for cars, appliances, and new furniture after the end of World War II quickly

expanded into the mass consumption of goods, services, and recreational

materials during the Fifties. Between 1945 and 1960, GNP grew by 250%,

expenditures on new construction multiplied nine times, and consumption on

personal services increased three times. By 1960, per capita income was 35%

higher than in 1945, and America had entered what the economist Walt Rostow

referred to as the "high mass consumption" stage of economic

development. Short-term credit went up from $8.4 billion in 1946 to $45.6

billion in 1958.

As a result of the postwar economic boom, 60% of the American

population had attained a "middle-class" standard of living by the

mid-50s (defined as incomes of $3,000 to $10,000 in constant dollars), compared

with only 31% in the last year of prosperity before the onset of the Great

Depression.

Television, too, had a powerful impact on social and economic patterns. Developed in the 1930s, it was not widely marketed until after the war. In 1946 the country had fewer than 17,000 television sets.Three years later consumers were buying 250,000 sets a month, and by 1960 three-quarters of all families owned at least one set. In the middle of the decade, the average family watched television four to five hours a day. Popular shows for children included Howdy Doody Time and The Mickey Mouse Club; older viewers preferred situation comedies like I Love Lucy and Father Knows Best. Americans of all ages became exposed to increasingly sophisticated advertisements for products said to be necessary for the good life.

By the end of the decade, 87% of families owned a TV set, 75% a

car, and 75% a washing machine. Between 1947 and 1960, the average real income

for American workers increased by as much as it had in the previous

half-century.

Television, too, had a powerful impact on social and economic patterns. Developed in the 1930s, it was not widely marketed until after the war. In 1946 the country had fewer than 17,000 television sets.Three years later consumers were buying 250,000 sets a month, and by 1960 three-quarters of all families owned at least one set. In the middle of the decade, the average family watched television four to five hours a day. Popular shows for children included Howdy Doody Time and The Mickey Mouse Club; older viewers preferred situation comedies like I Love Lucy and Father Knows Best. Americans of all ages became exposed to increasingly sophisticated advertisements for products said to be necessary for the good life.

With the prosperity of the era, the prevailing social

attitude was one of belief in science, technology, progress, and futurism.

There was comparatively little nostalgia for the prewar era and the overall

emphasis was on having everything new and more advanced than before.

Nonetheless, the social conformity and consumerism of the 1950s often came

under attack from intellectuals (e.g. Henry Miller's books The Air-Conditioned

Nightmare and Sunday After The War) and there was a good

deal of unrest fermenting under the surface of American society that would

erupt during the following decade.

In addition to the huge domestic market for consumer items, the United States became "the world's factory", as it was the only major power who's soil had been untouched by the war. American money and manufactured goods flooded into Europe, South Korea, and Japan and helped in their reconstruction. US manufacturing dominance would be almost unchallenged for a quarter-century after 1945.

In addition to the huge domestic market for consumer items, the United States became "the world's factory", as it was the only major power who's soil had been untouched by the war. American money and manufactured goods flooded into Europe, South Korea, and Japan and helped in their reconstruction. US manufacturing dominance would be almost unchallenged for a quarter-century after 1945.

One of the key factors in postwar prosperity was a

technology boom due to the experience of the war. Manufacturing had made

enormous strides and it was now possible to produce consumer goods in

quantities and levels of sophistication unseen before 1945. Acquisition of

technology from occupied Germany also proved an asset, as it was sometimes more

advanced than its American counterpart, especially in the optics and audio

equipment fields. The typical automobile in 1950 was an average of $300 more

expensive than the 1940 version, but also produced in twice the numbers. Luxury

makes such as Cadillac, which had

been largely hand-built vehicles only available to the rich, now became a

mass-produced car within the price range of the upper middle-class.

The rapid social and technological changes brought

about a growing corporatization of America and the decline of smaller

businesses, which often suffered from high postwar inflation and mounting

operating costs. Newspapers declined in numbers and consolidated, both due to

the above-mentioned factors and the event of TV news. The railroad industry,

once one of the cornerstones of the American economy and an immense and often

scorned influence on national politics, also suffered from the explosion in

automobile sales and the construction of the interstate system. By the end of

the 1950s, it was well into decline and by the 1970s became completely

bankrupt, necessitating a takeover by the federal government. Smaller

automobile manufacturers such as Nash, Studebaker, and Packard were unable to compete with the Big Three

in the new postwar world and gradually declined into oblivion over the next 15

years. Suburbanization caused the gradual movement of working-class people and

jobs out of the inner cities as shopping centers displaced the traditional

downtown stores. In time, this would have disastrous effects on urban areas.

Prosperity and overall optimism made Americans feel that it was a good time to bring children into the world, and so a huge baby boom resulted during the decade following 1945 (the baby boom climaxed during the mid-1950s, after which birthrates gradually dropped off until going below replacement level in 1965). Although the overall number of children per woman was not unusually high (averaging 2.3), they were assisted by improving technology that greatly brought down infant mortality rates versus the prewar era. Among other things, this resulted in an unprecedented demand for children's products and a huge expansion of the public school system. The large size of the postwar baby boom generation would have significant social repercussions in American society for decades to come.

Prosperity and overall optimism made Americans feel that it was a good time to bring children into the world, and so a huge baby boom resulted during the decade following 1945 (the baby boom climaxed during the mid-1950s, after which birthrates gradually dropped off until going below replacement level in 1965). Although the overall number of children per woman was not unusually high (averaging 2.3), they were assisted by improving technology that greatly brought down infant mortality rates versus the prewar era. Among other things, this resulted in an unprecedented demand for children's products and a huge expansion of the public school system. The large size of the postwar baby boom generation would have significant social repercussions in American society for decades to come.

Aside from the unfolding Civil Rights Movement, women

had been forced out of factories at the end of WWII for returning veterans and

many chafed at the social expectations of being an idle stay-at-home housewife

who cooked, cleaned, shopped, and tended to children. Alcohol and pill abuse

was not uncommon among American women during the 1950s, something quite

contrary to the idyllic image presented in TV shows such as Leave It To Beaver, The

Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, and Father Knows Best. In 1963, Betty Friedan publisher her book The Feminine Mystique which

strongly criticized the role of women during the postwar years and was a

best-seller and a major catalyst of the women's liberation movement.

Sociologists have noted that the "idle housewife" of the 1950s was

the exception in American history rather than the norm, where women generally

did work or labor in some capacity.

Prosperity also brought about the development of a distinct youth culture for the first time, as teenagers were not forced to work and support their family at young ages like in the past. This had its culmination in the development of new music genres such as rock-and-roll as well as fashion styles and subcultures, the most famous of which was the "greaser", a young male who drove motorcycles, sported ducktail haircuts (which were widely banned in schools) and displayed a general disregard for the law and authority. The greaser phenomenon was kicked off by the controversial youth-oriented movies Blackboard Jungle (1953) starring Marlon Brando and Rebel Without A Cause (1955) starring James Dean.

Prosperity also brought about the development of a distinct youth culture for the first time, as teenagers were not forced to work and support their family at young ages like in the past. This had its culmination in the development of new music genres such as rock-and-roll as well as fashion styles and subcultures, the most famous of which was the "greaser", a young male who drove motorcycles, sported ducktail haircuts (which were widely banned in schools) and displayed a general disregard for the law and authority. The greaser phenomenon was kicked off by the controversial youth-oriented movies Blackboard Jungle (1953) starring Marlon Brando and Rebel Without A Cause (1955) starring James Dean.

The American economy grew dramatically in the post-war

period, expanding at a rate of 3.5% per annum between 1945 and 1970. During

this period of prosperity, many incomes doubled in a generation, described by

economist Frank Levy as

"upward mobility on a rocket ship." The substantial increase in

average family income within a generation resulted in millions of office and

factory workers being lifted into a growing middle class, enabling them to

sustain a standard of living once considered to be reserved for the

wealthy. As noted by Deone Zell, assembly line work paid well, while

unionized factory jobs served as "stepping-stones to the middle class." By

the end of the Fifties, 87% of all American families owned at least one T.V.,

75% owned cars, and 60% owned their homes. By 1960, blue-collar workers

had become the biggest buyers of many luxury goods and services. In

addition, by the early 1970s, post-World War II American consumers enjoyed

higher levels of disposable income than those in any other country.

The great majority of American workers who had stable

jobs were well off financially, while even non-union jobs were associated with

rising paychecks, benefits, and obtained many of the advantages that

characterized union work. An upscale working class came into being, as

American blue-collar workers came to enjoy the benefits of home ownership,

while high wages provided blue-collar workers with the ability to pay for new

cars, household appliances, and regular vacations. By the 1960s, a

blue-collar worker earned more than a manager did in the 1940s, despite the

fact that his relative position within the income distribution had not changed.

As noted by the historian Nancy Wierek:

As noted by the historian Nancy Wierek:

"In the postwar period, the majority of Americans

were affluent in the sense that they were in a position to spend money on many

things they wanted, desired, or chose to have, rather than on necessities

alone."

Between 1946 and 1960, the United States witnessed a significant expansion in the consumption of goods and services. GNP rose by 36% and personal consumption expenditures by 42%, cumulative gains which were reflected in the incomes of families and unrelated individuals. While the number of these units rose sharply from 43.3 million to 56.1 million in 1960, a rise of almost 23%, their average incomes grew even faster, from $3940 in 1946 to $6900 in 1960, an increase of 43%. After taking inflation into account, the real advance was 16%. The dramatic rise in the average American standard of living was such that, according to sociologist George Katona:

"Today in this country minimum standards of

nutrition, housing and clothing are assured, not for all, but for the majority.

Beyond these minimum needs, such former luxuries as homeownership, durable

goods, travel, recreation, and entertainment are no longer restricted to a few.

The broad masses participate in enjoying all these things and generate most of

the demand for them."

More than 21 million housing units were constructed between 1946 and 1960, and in the latter year 52% of consumer units in the metropolitan areas owned their own homes. In 1957, out of all the wired homes throughout the country, 96% had a refrigerator, 87% an electric washer, 81% a television, 67% a vacuum cleaner, 18% a freezer, 12% an electric or gas dryer, and 8% air conditioning. Car ownership also soared, with 72% of consumer units owning an automobile by 1960. From 1958 to 1964, the average weekly take-home pay of blue-collar workers rose steadily from $68 to $78 (in constant dollars). In a poll taken in 1949, 50% of all Americans said that they were satisfied with their family income, a figure that rose to 67% by 1969.

More than 21 million housing units were constructed between 1946 and 1960, and in the latter year 52% of consumer units in the metropolitan areas owned their own homes. In 1957, out of all the wired homes throughout the country, 96% had a refrigerator, 87% an electric washer, 81% a television, 67% a vacuum cleaner, 18% a freezer, 12% an electric or gas dryer, and 8% air conditioning. Car ownership also soared, with 72% of consumer units owning an automobile by 1960. From 1958 to 1964, the average weekly take-home pay of blue-collar workers rose steadily from $68 to $78 (in constant dollars). In a poll taken in 1949, 50% of all Americans said that they were satisfied with their family income, a figure that rose to 67% by 1969.

The period from 1946 to 1960 also witnessed a

significant increase in the paid leisure time of working people. The forty-hour

workweek established by the Fair Labor Standards Act in covered industries

became the actual schedule in most workplaces by 1960, while uncovered workers

such as farm workers and the self-employed worked less hours than they had done

previously, although they still worked much longer hours than most other

workers. Paid vacations also came to be enjoyed by the vast majority of

workers, with 91% of blue-collar workers covered by major collective bargaining

agreements receiving paid vacations by 1957 (usually to a maximum of three

weeks), while by the early Sixties virtually all industries paid for holidays

and most did so for seven days a year. Industries catering to leisure

activities blossomed as a result of most Americans enjoying significant paid

leisure time by 1960, while many blue-collar and white-collar workers had

come to expect to hold on to their jobs for life.

Educational outlays were also greater than in other countries while a higher proportion of young people were graduating from high schools and universities than elsewhere in the world, as hundreds of new colleges and universities opened every year. Tuition was kept low—it was free at California state universities. At the advanced level American science, engineering and medicine was world famous. By the mid-Sixties, the majority of American workers enjoyed the highest wage levels in the world, and by the late Sixties, the great majority of Americans were richer than people in other countries, except Sweden, Switzerland, and Canada. Educational outlays were also greater than in other countries while a higher proportion of young people was at school and college than elsewhere in the world. As noted by the historian John Vaizey:

Educational outlays were also greater than in other countries while a higher proportion of young people were graduating from high schools and universities than elsewhere in the world, as hundreds of new colleges and universities opened every year. Tuition was kept low—it was free at California state universities. At the advanced level American science, engineering and medicine was world famous. By the mid-Sixties, the majority of American workers enjoyed the highest wage levels in the world, and by the late Sixties, the great majority of Americans were richer than people in other countries, except Sweden, Switzerland, and Canada. Educational outlays were also greater than in other countries while a higher proportion of young people was at school and college than elsewhere in the world. As noted by the historian John Vaizey:

"To strike a balance with the Soviet Union, it

would be easy to say that all but the very poorest Americans were better off

than the Russians, that education was better but the health service worse, but

that above all the Americans had freedom of expression and democratic

institutions."

In regards to social welfare, the postwar era saw a considerable improvement in insurance for workers and their dependents against the risks of illness, as private insurance programs like Blue Cross and Blue Shield expanded. With the exception of farm and domestic workers, virtually all members of the labor force were covered by Social Security. In 1959 that about two-thirds of the factory workers and three-fourths of the office workers were provided with supplemental private pension plans. In addition 86% of factory workers and 83% of office had jobs that covered for hospital insurance while 59% and 61% had additional insurance for doctors. By 1969, the average white family income had risen to $10,953, while average black family income lagged behind at $7,255, revealing a continued racial disparity in income amongst various segments of the American population. The percentage of American students staying on in education after the age of 15 was also higher than in most other developed countries, with more than 90% of 16-year-olds and around 75% of 17-year-olds in education in 1964-66.

In regards to social welfare, the postwar era saw a considerable improvement in insurance for workers and their dependents against the risks of illness, as private insurance programs like Blue Cross and Blue Shield expanded. With the exception of farm and domestic workers, virtually all members of the labor force were covered by Social Security. In 1959 that about two-thirds of the factory workers and three-fourths of the office workers were provided with supplemental private pension plans. In addition 86% of factory workers and 83% of office had jobs that covered for hospital insurance while 59% and 61% had additional insurance for doctors. By 1969, the average white family income had risen to $10,953, while average black family income lagged behind at $7,255, revealing a continued racial disparity in income amongst various segments of the American population. The percentage of American students staying on in education after the age of 15 was also higher than in most other developed countries, with more than 90% of 16-year-olds and around 75% of 17-year-olds in education in 1964-66.

B. Poverty

and inequality in the postwar era - despite the prosperity of the postwar era, a

significant minority of Americans continued to live in poverty by the end of

the Fifties. In 1947, 34% of all families earned less than $3,000 a year,

compared with 22.1% in 1960. Nevertheless, between one-fifth to one-fourth of

the population could not survive on the income they earned. The older generation

of Americans did not benefit as much from the postwar economic boom especially

as many had never recovered financially from the loss of their savings during

the Great Depression. It was generally a given that the average 35-year-old in

1959 owned a better house and car than the average 65-year-old, who typically

had nothing but a small Social Security pension for an income. Many blue-collar

workers continued to live in poverty, with 30% of those employed in industry in

1958 receiving under $3,000 a year. In addition, individuals who earned more

than $10,000 a year paid a lower proportion of their income in taxes than those

who earned less than $2,000 a year. In 1947, 60% of black families lived

below the poverty level (defined in one study as below $3000 in 1968 dollars),

compared with 23% of white families. In 1968, 23% of black families lived below

the poverty level, compared with 9% of white families. In 1947, 11% of white

families were affluent (defined as above $10,000 in 1968 dollars), compared

with 3% of black families. In 1968, 42% of white families were defined as

affluent, compared with 21% of black families. In 1947, 8% of black families

received $7000 or more (in 1968 dollars) compared with 26% of white families.

In 1968, 39% of black families received $7,000 or more, compared with 66% of

white families. In 1960, the median for a married man of blue-collar income was

$3,993 for blacks and $5,877 for whites. In 1969, the equivalent figures were

$5,746 and $7,452, respectively.

As Socialist leader Michael Harrington emphasized, there was still The Other America. Poverty declined sharply in the Sixties as the New Frontier and Great Society especially helped older people. The proportion below the poverty line fell almost in half from 22% in 1960 to 12% in 1970 and then leveled off.

C. Rural life - The farm population shrank steadily as families moved to urban areas, where on average they were more productive and earned a higher standard of living. Friedberger argues that the postwar period saw an accelerating mechanization of agriculture, combined with new and better fertilizers and genetic manipulation of hybrid corn. It made for greater specialization and greater economic risks for the farmer. With rising land prices many sold their land and moved to town, the old farm becoming part of a neighbor's enlarged operation. Mechanization meant less need for hired labor; farmers could operate more acres even though they were older. The result was a decline in rural-farm population, with gains in service centers that provided the new technology. The rural non-farm population grew as factories were attracted by access to good transportation without the high land costs, taxes, unionization and congestion of city factory districts. Once remote rural areas such as the Missouri Ozarks and the North Woods of the upper Midwest, with a rustic life style and many good fishing spots, have attracted retirees and vacationers.

D. The culture of the 1950s - during the 1950s, many cultural commentators pointed out that a sense of uniformity pervaded American society. Conformity, they asserted, was numbingly common. Though men and women had been forced into new employment patterns during World War II, once the war was over, traditional roles were reaffirmed. Men expected to be the breadwinners in each family; women, even when they worked, assumed their proper place was at home. In his influential book, The Lonely Crowd, sociologist David Riesman called this new society “other-directed,” characterized by conformity, but also by stability. Television, still very limited in the choices it gave its viewers, contributed to the homogenizing cultural trend by providing young and old with a shared experience reflecting accepted social patterns.

Yet beneath this seemingly bland surface, important segments of American society seethed with rebellion. A number of writers, collectively known as the “Beat Generation,” went out of their way to challenge the patterns of respectability and shock the rest of the culture. Stressing spontaneity and spirituality, they preferred intuition over reason, Eastern mysticism over Western institutionalized religion.

The literary work of the beats displayed their sense of alienation and quest for self-realization. Jack Kerouac typed his best-selling novel On the Road on a 75-meter roll of paper. Lacking traditional punctuation and paragraph structure, the book glorified the possibilities of the free life. Poet Allen Ginsberg gained similar notoriety for his poem “Howl,” a scathing critique of modern, mechanized civilization. When police charged that it was obscene and seized the published version, Ginsberg successfully challenged the ruling in court.

Musicians and artists rebelled as well. Tennessee singer Elvis Presley was the most successful of several white performers who popularized a sensual and pulsating style of African-American music, which began to be called “rock and roll.” At first, he outraged middle-class Americans with his ducktail haircut and undulating hips. But in a few years his performances would seem relatively tame alongside the antics of later performers such as the British Rolling Stones. Similarly, it was in the 1950s that painters like Jackson Pollock discarded easels and laid out gigantic canvases on the floor, then applied paint, sand, and other materials in wild splashes of color. All of these artists and authors, whatever the medium, provided models for the wider and more deeply felt social revolution of the 1960s.

E. Origins of the civil rights movement - African Americans became increasingly restive in the postwar years. During the war they had challenged discrimination in the military services and in the work force, and they had made limited gains. Millions of African Americans had left Southern farms for Northern cities, where they hoped to find better jobs. They found instead crowded conditions in urban slums. Now, African-American servicemen returned home, many intent on rejecting second-class citizenship.

Jackie Robinson dramatized the racial question in 1947 when he broke baseball’s color line and began playing in the major leagues. A member of the Brooklyn Dodgers, he often faced trouble with opponents and teammates as well. But an outstanding first season led to his acceptance and eased the way for other African-American players, who now left the Negro leagues to which they had been confined.

Government officials, and many other Americans, discovered the connection between racial problems and Cold War politics. As the leader of the free world, the United States sought support in Africa and Asia. Discrimination at home impeded the effort to win friends in other parts of the world.

Harry Truman supported the early civil rights movement. He personally believed in political equality, though not in social equality, and recognized the growing importance of the African-American urban vote. When apprised in 1946 of a spate of lynchings and anti-black violence in the South, he appointed a committee on civil rights to investigate discrimination. Its report, To Secure These Rights, issued the next year, documented African Americans’ second-class status in American life and recommended numerous federal measures to secure the rights guaranteed to all citizens.

Truman responded by sending a 10-point civil rights program to Congress. Southern Democrats in Congress were able to block its enactment. A number of the angriest, led by Governor Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, formed a States Rights Party to oppose the president in 1948. Truman thereupon issued an executive order barring discrimination in federal employment, ordered equal treatment in the armed forces, and appointed a committee to work toward an end to military segregation, which was largely ended during the Korean War.

African Americans in the South in the 1950s still enjoyed few, if any, civil and political rights. In general, they could not vote. Those who tried to register faced the likelihood of beatings, loss of job, loss of credit, or eviction from their land. Occasional lynchings still occurred. Jim Crow laws enforced segregation of the races in streetcars, trains, hotels, restaurants, hospitals, recreational facilities, and employment.

Following the end of Reconstruction, many states adopted restrictive Jim Crow laws which enforced segregation of the races and the second-class status of African Americans. The Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson 1896 accepted segregation as constitutional. Voting rights discrimination remained widespread in the South through the 1950s. Fewer than 10% voted in the Deep South, although a larger proportion voted in the border states, and the blacks were being organized into Democratic machines in the northern cities. Although both parties pledged progress in 1948, the only major development before 1954 was the integration of the military.

As Socialist leader Michael Harrington emphasized, there was still The Other America. Poverty declined sharply in the Sixties as the New Frontier and Great Society especially helped older people. The proportion below the poverty line fell almost in half from 22% in 1960 to 12% in 1970 and then leveled off.

C. Rural life - The farm population shrank steadily as families moved to urban areas, where on average they were more productive and earned a higher standard of living. Friedberger argues that the postwar period saw an accelerating mechanization of agriculture, combined with new and better fertilizers and genetic manipulation of hybrid corn. It made for greater specialization and greater economic risks for the farmer. With rising land prices many sold their land and moved to town, the old farm becoming part of a neighbor's enlarged operation. Mechanization meant less need for hired labor; farmers could operate more acres even though they were older. The result was a decline in rural-farm population, with gains in service centers that provided the new technology. The rural non-farm population grew as factories were attracted by access to good transportation without the high land costs, taxes, unionization and congestion of city factory districts. Once remote rural areas such as the Missouri Ozarks and the North Woods of the upper Midwest, with a rustic life style and many good fishing spots, have attracted retirees and vacationers.

D. The culture of the 1950s - during the 1950s, many cultural commentators pointed out that a sense of uniformity pervaded American society. Conformity, they asserted, was numbingly common. Though men and women had been forced into new employment patterns during World War II, once the war was over, traditional roles were reaffirmed. Men expected to be the breadwinners in each family; women, even when they worked, assumed their proper place was at home. In his influential book, The Lonely Crowd, sociologist David Riesman called this new society “other-directed,” characterized by conformity, but also by stability. Television, still very limited in the choices it gave its viewers, contributed to the homogenizing cultural trend by providing young and old with a shared experience reflecting accepted social patterns.

Yet beneath this seemingly bland surface, important segments of American society seethed with rebellion. A number of writers, collectively known as the “Beat Generation,” went out of their way to challenge the patterns of respectability and shock the rest of the culture. Stressing spontaneity and spirituality, they preferred intuition over reason, Eastern mysticism over Western institutionalized religion.

The literary work of the beats displayed their sense of alienation and quest for self-realization. Jack Kerouac typed his best-selling novel On the Road on a 75-meter roll of paper. Lacking traditional punctuation and paragraph structure, the book glorified the possibilities of the free life. Poet Allen Ginsberg gained similar notoriety for his poem “Howl,” a scathing critique of modern, mechanized civilization. When police charged that it was obscene and seized the published version, Ginsberg successfully challenged the ruling in court.

Musicians and artists rebelled as well. Tennessee singer Elvis Presley was the most successful of several white performers who popularized a sensual and pulsating style of African-American music, which began to be called “rock and roll.” At first, he outraged middle-class Americans with his ducktail haircut and undulating hips. But in a few years his performances would seem relatively tame alongside the antics of later performers such as the British Rolling Stones. Similarly, it was in the 1950s that painters like Jackson Pollock discarded easels and laid out gigantic canvases on the floor, then applied paint, sand, and other materials in wild splashes of color. All of these artists and authors, whatever the medium, provided models for the wider and more deeply felt social revolution of the 1960s.