The War of

1812 was, in a sense, a second war of independence, for before that time the

United States had not been accorded equality in the family of nations. With its

conclusion, many of the serious difficulties that the young republic had faced

since the Revolution now disappeared. National union under the Constitution

brought a balance between liberty and order. With a low national debt and a

continent awaiting exploration, the prospect of peace, prosperity and social

progress opened before the nation.

1. Building unity and era of good feelings (1816-1825)

A. General characteristic of the period - commerce was cementing national unity. The privations of war convinced many of the importance of protecting the manufacturers of America until they could stand alone against foreign competition. Economic independence, many argued, was as essential as political independence. To foster self-sufficiency, congressional leaders Henry Clay of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina urged a policy of protectionism - imposition of restrictions on imported goods to foster the development of American industry.

The time was

propitious for raising the customs tariff. The shepherds of Vermont and Ohio

wanted protection against an influx of English wool. In Kentucky, a new

industry of weaving local hemp into cotton bagging was threatened by the

Scottish bagging industry. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, already a flourishing

center of iron smelting, was eager to challenge British and Swedish iron

suppliers. The tariff enacted in 1816 imposed duties high enough to give

manufacturers real protection. In addition, Westerners advocated a national

system of roads and canals to link them with Eastern cities and ports, and to

open frontier lands for settlement. However, they were unsuccessful in pressing

their demands for a federal role in internal improvement because of opposition

from New England and the South. Roads and canals remained the province of the

states until the passage of the Federal Highways Act of 1916.

The position

of the federal government at this time was greatly strengthened by several

Supreme Court decisions. A committed Federalist, John Marshall of Virginia,

became chief justice in 1801 and held office until his death in 1835. The court

- weak before his administration - was transformed into a powerful tribunal,

occupying a position co-equal to the Congress and the president. In a

succession of historic decisions, Marshall never deviated from one cardinal

principle: upholding the sovereignty of the Constitution.

Marshall was

the first in a long line of Supreme Court justices whose decisions have molded

the meaning and application of the Constitution. When he finished his long service,

the court had decided nearly 50 cases clearly involving constitutional issues.

In one of Marshall's most famous opinions - Marbury v. Madison (1803)

- he decisively established the right of the Supreme Court to review the

constitutionality of any law of Congress or of a state legislature. In McCulloch v.

Maryland (1819), which dealt with the old question of the implied powers of

the government under the Constitution, he stood boldly in defense of the

Hamiltonian theory that the Constitution by implication gives the government

powers beyond those expressly stated.

B. Latin America and the Monroe doctrine - during the

opening decades of the 19th century, Central and South America turned to

revolution. The idea of liberty had stirred the people of Latin America from

the time the English colonies gained their freedom. Napoleon's conquest of

Spain in 1808 provided the signal for Latin Americans to rise in revolt. By

1822, ably led by Simon Bolivar, Francisco Miranda, Jose de San Martin and

Miguel Hidalgo, all of Hispanic America - from Argentina and Chile in the

south to Mexico and California in the north - had won independence from the

mother country.

The people of

the United States took a deep interest in what seemed a repetition of their own

experience in breaking away from European rule. The Latin American independence

movements confirmed their own belief in self-government. In 1822 President

James Monroe, under powerful public pressure, received authority to recognize

the new countries of Latin America -- including the former Portuguese colony of

Brazil -- and soon exchanged ministers with them. This recognition confirmed

their status as genuinely independent countries, entirely separated from their

former European connections.

At just this

point, Russia, Prussia and Austria formed an association called the Holy

Alliance to protect themselves against revolution. By intervening in countries

where popular movements threatened monarchies, the Alliance -- joined at times

by France -- hoped to prevent the spread of revolution into its dominions. This

policy was the antithesis of the American principle of self-determination.

|

| President James Monroe, portrait by John Vanderlyn, 1816 |

The Monroe Doctrine, expressed in 1823, proclaimed the United States' opinion that European powers should no longer colonize or interfere in the Americas. This was a defining moment in the foreign policy of the United States. The Monroe Doctrine was adopted in response to American and British fears over Russian and French expansion into the Western Hemisphere.

As long as the Holy Alliance confined its activities to the Old World, it aroused no anxiety in the United States. But when the Alliance announced its intention of restoring its former colonies to Spain, Americans became very concerned. For its part, Britain resolved to prevent Spain from restoring its empire because trade with Latin America was too important to British commercial interests. London urged the extension of Anglo-American guarantees to Latin America, but Secretary of State John Quincy Adams convinced Monroe to act unilaterally: "It would be more candid, as well as more dignified, to avow our principles explicitly to Russia and France, than to come in as a cock-boat in the wake of the British man-of-war." In December 1823, with the knowledge that the British navy would defend Latin America from the Holy Alliance and France, President Monroe took the occasion of his annual message to Congress to pronounce what would become known as the Monroe Doctrine -- the refusal to tolerate any further extension of European domination in the Americas:

As long as the Holy Alliance confined its activities to the Old World, it aroused no anxiety in the United States. But when the Alliance announced its intention of restoring its former colonies to Spain, Americans became very concerned. For its part, Britain resolved to prevent Spain from restoring its empire because trade with Latin America was too important to British commercial interests. London urged the extension of Anglo-American guarantees to Latin America, but Secretary of State John Quincy Adams convinced Monroe to act unilaterally: "It would be more candid, as well as more dignified, to avow our principles explicitly to Russia and France, than to come in as a cock-boat in the wake of the British man-of-war." In December 1823, with the knowledge that the British navy would defend Latin America from the Holy Alliance and France, President Monroe took the occasion of his annual message to Congress to pronounce what would become known as the Monroe Doctrine -- the refusal to tolerate any further extension of European domination in the Americas:

The American

continents...are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future

colonization by any European powers.

We should

consider any attempt on their part to extend their [political] system to any

portion of this hemisphere as dangerous to our peace and safety.

With the

existing colonies or dependencies of any European power we have not interfered

and shall not interfere. But with the governments who have declared their

independence and maintained it, and whose independence we have...acknowledged,

we could not view any interposition for the purpose of oppressing them, or

controlling in any other manner their destiny, by any European power in any

other light than as the manifestation of an unfriendly disposition toward the

United States.

The Monroe

Doctrine expressed a spirit of solidarity with the newly independent republics

of Latin America. These nations in turn recognized their political affinity

with the United States by basing their new constitutions, in many instances, on

the North American model.

C. Factionalism, political parties and presidency of John Adams - domestically,

the presidency of Monroe (1817-1825) was termed the "era of good

feelings." In one sense, this term disguised a period of vigorous

factional and regional conflict; on the other hand, the phrase acknowledged the

political triumph of the Republican Party over the Federalist Party, which

collapsed as a national force.

The decline of

the Federalists brought disarray to the system of choosing presidents. At the

time, state legislatures could nominate candidates. In 1824 Tennessee and

Pennsylvania chose Andrew Jackson, with South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun

as his running mate. Kentucky selected Speaker of the House Henry Clay;

Massachusetts, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams; and a congressional

caucus, Treasury Secretary William Crawford.

Personality

and sectional allegiance played important roles in determining the outcome of

the election. Adams won the electoral votes from New England and most of New

York; Clay won Kentucky, Ohio and Missouri; Jackson won the Southeast,

Illinois, Indiana, the Carolinas, Pennsylvania, Maryland and New Jersey; and

Crawford won Virginia, Georgia and Delaware. No candidate gained a majority in

the Electoral College, so, according to the provisions of the Constitution, the

election was thrown into the House of Representatives, where Clay was the most

influential figure. He supported Adams, who gained the presidency.

During Adams's

administration, new party alignments appeared. Adams's followers took the name

of "National Republicans," later to be changed to "Whigs."

Though he governed honestly and efficiently, Adams was not a popular president,

and his administration was marked with frustrations. Adams failed in his effort

to institute a national system of roads and canals. His years in office

appeared to be one long campaign for reelection, and his coldly intellectual

temperament did not win friends. Jackson, by contrast, had enormous popular

appeal, especially among his followers in the newly named Democratic Party that

emerged from the Republican Party, with its roots dating back to presidents

Jefferson, Madison and Monroe. In the election of 1828, Jackson defeated Adams

by an overwhelming electoral majority.

2. Presidensy of Jackson (1829-1837)

Tennessee politician, Indian fighter and hero of the Battle of New Orleans

during the War of 1812 - drew his support from the small farmers of the West,

and the workers, artisans and small merchants of the East, who sought to use

their vote to resist the rising commercial and manufacturing interests

associated with the Industrial Revolution.

As strong opponents of the war, the Federalists held the Hartford Convention in 1814 that hinted at disunion. National euphoria after the victory at New Orleans ruined the prestige of the Federalists and they no longer played a significant role. President Madison and most Republicans realized they were foolish to let the Bank of the United States close down, for its absence greatly hindered the financing of the war. So, with the assistance of foreign bankers, they chartered the Second Bank of the United States in 1816.

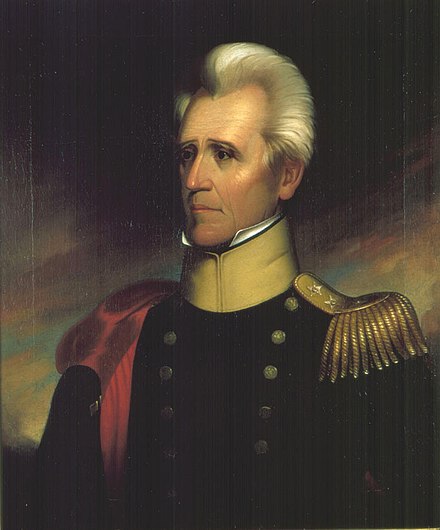

|

| Portrait by Ralph E. W. Earl, c. 1837 |

The Republicans also imposed tariffs designed to protect the infant industries that had been created when Britain was blockading the U.S. With the collapse of the Federalists as a party, the adoption of many Federalist principles by the Republicans, and the systematic policy of President James Monroe in his two terms (1817–25) to downplay partisanship, the nation entered an Era of Good Feelings, with far less partisanship than before (or after), and closed out the First Party System.

The election of 1828 was a significant benchmark in the trend toward broader voter participation. Vermont had universal male suffrage from its entry into the Union and Tennessee permitted suffrage for the vast majority of taxpayers. New Jersey, Maryland and South Carolina all abolished property and tax-paying requirements between 1807 and 1810. States entering the Union after 1815 either had universal white male suffrage or a low taxpaying requirement. From 1815 to 1821, Connecticut, Massachusetts and New York abolished all property requirements. In 1824 members of the Electoral College were still selected by six state legislatures. By 1828 presidential electors were chosen by popular vote in every state but Delaware and South Carolina. Nothing dramatized this democratic sentiment more than the election of the flamboyant Andrew Jackson.

A. Nullification crisis - toward the end

of his first term in office, Jackson was forced to confront the state of South

Carolina on the issue of the protective tariff. Business and farming interests

in the state had hoped that Jackson would use his presidential power to modify

tariff laws they had long opposed. In their view, all the benefits of

protection were going to Northern manufacturers, and while the country as a

whole grew richer, South Carolina grew poorer, with its planters bearing the

burden of higher prices.

The protective

tariff passed by Congress and signed into law by Jackson in 1832 was milder

than that of 1828, but it further embittered many in the state. In response, a

number of South Carolina citizens endorsed the states' rights principle of

"nullification," which was enunciated by John C. Calhoun, Jackson's

vice president until 1832, in his South Carolina Exposition and Protest (1828).

South Carolina dealt with the tariff by adopting the Ordinance of

Nullification, which declared both the tariffs of 1828 and 1832 null and void

within state borders. The legislature also passed laws to enforce the

ordinance, including authorization for raising a military force and appropriations

for arms.

Nullification

was only the most recent in a series of state challenges to the authority of

the federal government. There had been a continuing contest between the states

and the national government over the power of the latter, and over the loyalty

of the citizenry, almost since the founding of the republic. The Kentucky and

Virginia Resolutions of 1798, for example, had defied the Alien and Sedition

Acts, and in the Hartford Convention, New England voiced its opposition to

President Madison and the war against the British.

In response to

South Carolina's threat, Jackson sent seven small naval vessels and a

man-of-war to Charleston in November 1832. On December 10, he issued a

resounding proclamation against the nullifiers. South Carolina, the president

declared, stood on "the brink of insurrection and treason," and he

appealed to the people of the state to reassert their allegiance to that Union

for which their ancestors had fought.

When the

question of tariff duties again came before Congress, it soon became clear that

only one man, Senator Henry Clay, the great advocate of protection (and a

political rival of Jackson), could pilot a compromise measure through Congress.

Clay's tariff bill - quickly passed in 1833 - specified that all duties in

excess of 20 percent of the value of the goods imported were to be reduced by

easy stages, so that by 1842, the duties on all articles would reach the level

of the moderate tariff of 1816.

Nullification

leaders in South Carolina had expected the support of other Southern states,

but without exception, the rest of the South declared South Carolina's course

unwise and unconstitutional. Eventually, South Carolina rescinded its action.

Both sides, nevertheless, claimed victory. Jackson had committed the federal

government to the principle of Union supremacy. But South Carolina, by its show

of resistance, had obtained many of the demands it sought, and had demonstrated

that a single state could force its will on Congress.

B. Battle of the bank - even before

the nullification issue had been settled, another controversy occurred that

challenged Jackson's leadership. It concerned the rechartering of the second

Bank of the United States. The first bank had been established in 1791, under

Alexander Hamilton's guidance, and had been chartered for a 20-year period.

Though the government held some of its stock, it was not a government bank;

rather, the bank was a private corporation with profits passing to its

stockholders. It had been designed to stabilize the currency and stimulate

trade; but it was resented by Westerners and working people who believed, along

with Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, that it was a "monster"

granting special favors to a few powerful men. When its charter expired in

1811, it was not renewed.

For the next

few years, the banking business was in the hands of state-chartered banks,

which issued currency in excessive amounts, creating great confusion and

fueling inflation. It became increasingly clear that state banks could not

provide the country with a uniform currency, and in 1816 a second Bank of the

United States, similar to the first, was again chartered for 20 years.

From its

inception, the second Bank was unpopular in the newer states and territories,

and with less prosperous people everywhere. Opponents claimed the bank

possessed a virtual monopoly over the country's credit and currency, and

reiterated that it represented the interests of the wealthy few. On the whole,

the bank was well managed and rendered valuable service; but Jackson, elected

as a popular champion against it, vetoed a bill to recharter the bank. In his

message to Congress, he denounced monopoly and special privilege, saying that

"our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal

benefits, but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress."

The effort to override the veto failed.

In 1832, President Andrew Jackson, 7th President of the United States, ran for a second term under the slogan "Jackson and no bank" and didn't renew the charter of the Second Bank of the United States of America. Jackson was convinced that central banking was used by the elite to take advantage of the average American.

In the

election campaign that followed, the bank question caused a fundamental

division between the merchant, manufacturing and financial interests (generally

creditors who favored tight money and high interest rates), and the laboring

and agrarian elements, who were often in debt to banks and therefore favored an

increased money supply and lower interest rates. The outcome was an

enthusiastic endorsement of "Jacksonism." Jackson saw his reelection

in 1832 as a popular mandate to crush the bank irrevocably - and found a

ready-made weapon in a provision of the bank's charter authorizing removal of

public funds. In September 1833 he ordered that no more government money be

deposited in the bank, and that the money already in its custody be gradually

withdrawn in the ordinary course of meeting the expenses of government.

Carefully selected state banks, stringently restricted, were provided as a

substitute. For the next generation the United States would get by on a

relatively unregulated state banking system, which helped fuel westward

expansion through cheap credit but kept the nation vulnerable to periodic

panics. It wasn't until the Civil War that the United States chartered a

national banking system.

C. Whigs, Democrats and "know-nothings"

Second Party System - after the First Party System of Federalists and Republicans withered away in the 1820s, the stage was set for the emergence of a new party system based on very well organized local parties that appealed for the votes of (almost) all adult white men. The former Jeffersonian party split into factions. They split over the choice of a successor to President James Monroe, and the party faction that supported many of the old Jeffersonian principles, led by Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren, became the Democratic Party. As Norton explains the transformation in 1828:

Second Party System - after the First Party System of Federalists and Republicans withered away in the 1820s, the stage was set for the emergence of a new party system based on very well organized local parties that appealed for the votes of (almost) all adult white men. The former Jeffersonian party split into factions. They split over the choice of a successor to President James Monroe, and the party faction that supported many of the old Jeffersonian principles, led by Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren, became the Democratic Party. As Norton explains the transformation in 1828:

Jacksonians believed the people's will had finally prevailed. Through a lavishly financed coalition of state parties, political leaders, and newspaper editors, a popular movement had elected the president. The Democrats became the nation's first well-organized national party...and tight party organization became the hallmark of nineteenth-century American politics.

Opposing factions led by Henry Clay helped form the Whig Party. The Democratic Party had a small but decisive advantage over the Whigs until the 1850s, when the Whigs fell apart over the issue of slavery.

Behind the platforms issued by state and national parties stood a widely shared political outlook that characterized the Democrats:

The Democrats represented a wide range of views but shared a fundamental commitment to the Jeffersonian concept of an agrarian society. They viewed the central government as the enemy of individual liberty. The 1824 "corrupt bargain" had strengthened their suspicion of Washington politics....Jacksonians feared the concentration of economic and political power. They believed that government intervention in the economy benefited special-interest groups and created corporate monopolies that favored the rich. They sought to restore the independence of the individual--the artisan and the ordinary farmer--by ending federal support of banks and corporations and restricting the use of paper currency, which they distrusted. Their definition of the proper role of government tended to be negative, and Jackson's political power was largely expressed in negative acts. He exercised the veto more than all previous presidents combined. Jackson and his supporters also opposed reform as a movement. Reformers eager to turn their programs into legislation called for a more active government. But Democrats tended to oppose programs like educational reform mid the establishment of a public education system. They believed, for instance, that public schools restricted individual liberty by interfering with parental responsibility and undermined freedom of religion by replacing church schools. Nor did Jackson share reformers' humanitarian concerns. He had no sympathy for American Indians, initiating the removal of the Cherokees along the Trail of Tears.Behind the platforms issued by state and national parties stood a widely shared political outlook that characterized the Democrats:

An economic

depression and the larger-than-life personality of his predecessor obscured Van

Buren's merits. His public acts aroused no enthusiasm, for he lacked the

compelling qualities of leadership and the dramatic flair that had attended

Jackson's every move. The election of 1840 found the country afflicted with

hard times and low wages and the Democrats on the defensive.

The Whig

candidate for president was William Henry Harrison of Ohio, vastly popular as a

hero of Indian conflicts as well as the War of 1812. He was regarded, like

Jackson, as a representative of the democratic West. His vice presidential

candidate was John Tyler - a Virginian whose views on states' rights and a low

tariff were popular in the South. Harrison won a sweeping victory.

Within a month

of his inauguration, however, the 68-year-old Harrison died, and Tyler became

president. Tyler's beliefs differed sharply from those of Clay and Webster,

still the most influential men in the country. Before Tyler's term was over,

these differences led to an open break between the president and the party that

had elected him.

Americans,

however, found themselves divided in more complex ways than simple partisan

conflicts between Whigs and Democrats. For example, the large number of

Catholic immigrants in the first half of the 19th century, primarily Irish and

German, triggered a backlash among native-born Protestant Americans.

Immigrants

brought more than strange new customs and religious practices to American

shores. They competed with the native-born for jobs in cities along the Eastern

seaboard. Moreover, political changes in the 1820s and 1830s increased the

political clout of the foreign born. During those two decades, state

constitutions were revised to permit universal white-male suffrage. This led to

the end of rule by patrician politicians, who blamed the immigrants for their

fall from power. Finally, the Catholic Church's failure to support the

temperance movement gave rise to charges that Rome was trying to subvert the

United States through alcohol.

The most

important of the nativist organizations that sprang up in this period was a

secret society, the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, founded in 1849. When

its members refused to identify themselves, they were swiftly labeled the

"Know-Nothings." In 1853 the Know-Nothings in New York City organized

a Grand Council, which devised a new constitution to centralize control over

the state organizations.

Among the

chief aims of the Know-Nothings were an extension in the period required for

naturalization from five to 21 years, and the exclusion of the foreign-born and

Catholics from public office. In 1855 the organization managed to win control

of legislatures in New York and Massachusetts; by 1855, about 90 U.S.

congressmen were linked to the party.

Disagreements

over the slavery issue prevented the party from playing a role in national

politics. The Know-Nothings of the South supported slavery while Northern

members opposed it. At a convention in 1856 to nominate candidates for

president and vice president, 42 Northern delegates walked out when a motion to

support the Missouri Compromise was ignored, and the party died as a national

force.

D. Indian removal

D. Indian removal

Settlers crossing the Plains of Nebraska.

In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which authorized the president to negotiate treaties that exchanged Native American tribal lands in the eastern states for lands west of the Mississippi River. Its goal was primarily to remove Native Americans, including the Five Civilized Tribes, from the American Southeast; they occupied land that settlers wanted. Jacksonian Democrats demanded the forcible removal of native populations who refused to acknowledge state laws to reservations in the West; Whigs and religious leaders opposed the move as inhumane. Thousands of deaths resulted from the relocations, as seen in the Cherokee Trail of Tears. Many of the Seminole Indians in Florida refused to move west; they fought the Army for years in the Seminole Wars.

A. Second Great Awakening

3. 19-th century reforms

A. Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant revival movement that affected the entire nation during the early 19th century and led to rapid church growth. The movement began around 1790, gained momentum by 1800, and, after 1820 membership rose rapidly among Baptist and Methodist congregations, whose preachers led the movement. It was past its peak by the 1840s.

|

| A drawing of a Protestant camp meeting, 1829. |

It enrolled millions of new members in existing evangelical denominations and led to the formation of new denominations. Many converts believed that the Awakening heralded a new millennial age. The Second Great Awakening stimulated the establishment of many reform movements – including abolitionism and temperance designed to remove the evils of society before the anticipated Second Coming of Jesus Christ.

B. Strings of reform - the democratic

upheaval in politics exemplified by Jackson's election was merely one phase of

the long American quest for greater rights and opportunities for all citizens.

Another was the beginning of labor organization. In 1835 labor forces in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, succeeded in reducing the old

"dark-to-dark" workday to a 10-hour day. New Hampshire, Rhode Island,

Ohio and the new state of California, admitted to the Union in 1850, undertook

similar reforms.

The spread of

suffrage had already led to a new concept of education, for clear-sighted

statesmen everywhere perceived the threat to universal suffrage from an

untutored, illiterate electorate. These men - DeWitt Clinton in New York,

Abraham Lincoln in Illinois and Horace Mann in Massachusetts - were now

supported by organized labor, whose leaders demanded free, tax-supported

schools open to all children. Gradually, in one state after another,

legislation was enacted to provide for such free instruction. The public school

system became common throughout the northern part of the country. In other

parts of the country, however, the battle for public education continued for

years.

Another

influential social movement that emerged during this period was the opposition

to the sale and use of alcohol, or the temperance movement. It stemmed from a

variety of concerns and motives: religious beliefs, the effect of alcohol on

the work force, and the violence and suffering women and children experienced

at the hands of heavy drinkers. In 1826 Boston ministers organized the Society

for the Promotion of Temperance. Seven years later, in Philadelphia, the

Society convened a national convention, which formed the American Temperance

Union. The Union called for the renunciation of all alcoholic beverages, and

pressed state legislatures to ban their production and sale. Thirteen states

had done so by 1855, although the laws were subsequently challenged in court.

They survived only in northern New England, but between 1830 and 1860 the

temperance movement reduced Americans' per capita consumption of alcohol.

Other

reformers addressed the problems of prisons and care for the insane. Efforts

were made to turn prisons, which stressed punishment, into penitentiaries,

where the guilty would undergo rehabilitation. In Massachusetts, Dorothea Dix

led a struggle to improve conditions for insane persons, who were kept confined

in wretched almshouses and prisons. After winning improvements in

Massachusetts, she took her campaign to the South, where nine states

established hospitals for the insane between 1845 and 1852.

C. Women's rights

Such social reforms brought many women to a realization of their own unequal position in society. From colonial times, unmarried women had enjoyed many of the same legal rights as men, although custom required that they marry early. With matrimony, women virtually lost their separate identities in the eyes of the law. Women were not permitted to vote and their education in the 17th and 18th centuries was limited largely to reading, writing, music, dancing and needlework.

Such social reforms brought many women to a realization of their own unequal position in society. From colonial times, unmarried women had enjoyed many of the same legal rights as men, although custom required that they marry early. With matrimony, women virtually lost their separate identities in the eyes of the law. Women were not permitted to vote and their education in the 17th and 18th centuries was limited largely to reading, writing, music, dancing and needlework.

The awakening

of women began with the visit to America of Frances Wright, a Scottish lecturer

and journalist, who publicly promoted women's rights throughout the United

States during the 1820s. At a time when women were often forbidden to speak in

public places, Wright not only spoke out, but shocked audiences by her views

advocating the rights of women to seek information on birth control and

divorce.

By the 1840s a

group of American women emerged who would forge the first women's rights movement.

Foremost in this distinguished group was Elizabeth Cady Stanton. In 1848 Cady

Stanton and Lucretia Mott, another women's rights advocate, organized a women's

rights convention - the first in the history of the world at Seneca Falls,

New York. Delegates drew up a declaration demanding equality with men before

the law, the right to vote, and equal opportunities in education and

employment.

That same

year, Ernestine Rose, a Polish immigrant, was instrumental in getting a law

passed in the state of New York that allowed married women to keep their

property in their own name. Among the first laws in the nation of this kind,

the Married Women's Property Act, encouraged other state legislatures to enact

similar laws.

In 1869 Rose helped Elizabeth Cady Stanton and another leading women's rights activist, Susan B. Anthony, to found the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which advocated a constitutional amendment for women's right to the vote. These two would become the women's movement's most outspoken advocates. Describing their partnership, Cady Stanton would say, "I forged the thunderbolts and she fired them."

D. Extension of slavery and Abolitionism

Slavery, which had up to now received little public attention, began to assume much greater importance as a national issue. In the early years of the republic, when the Northern states were providing for immediate or gradual emancipation of the slaves, many leaders had supposed that slavery would die out. In 1786 George Washington wrote that he devoutly wished some plan might be adopted "by which slavery may be abolished by slow, sure and imperceptible degrees." Jefferson, Madison and Monroe, all Virginians, and other leading Southern statesmen, made similar statements. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had banned slavery in the Northwest Territory. As late as 1808, when the international slave trade was abolished, there were many Southerners who thought that slavery would soon end. The expectation proved false, for during the next generation, the South became solidly united behind the institution of slavery as new economic factors made slavery far more profitable than it had been before 1790.

Slavery, which had up to now received little public attention, began to assume much greater importance as a national issue. In the early years of the republic, when the Northern states were providing for immediate or gradual emancipation of the slaves, many leaders had supposed that slavery would die out. In 1786 George Washington wrote that he devoutly wished some plan might be adopted "by which slavery may be abolished by slow, sure and imperceptible degrees." Jefferson, Madison and Monroe, all Virginians, and other leading Southern statesmen, made similar statements. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had banned slavery in the Northwest Territory. As late as 1808, when the international slave trade was abolished, there were many Southerners who thought that slavery would soon end. The expectation proved false, for during the next generation, the South became solidly united behind the institution of slavery as new economic factors made slavery far more profitable than it had been before 1790.

after 1840 the growing abolitionist movement redefined itself as a crusade against the sin of slave ownership. It mobilized support (especially among religious women in the Northeast affected by the Second Great Awakening).

William Lloyd Garrison published the most influential of the many anti-slavery newspapers, The Liberator, while Frederick Douglass, an ex-slave, began writing for that newspaper around 1840 and started his own abolitionist newspaper North Star in 1847. The great majority of anti-slavery activists, such as Abraham Lincoln, rejected Garrison's theology and held that slavery was an unfortunate social evil, not a sin.

In 1869 Rose helped Elizabeth Cady Stanton and another leading women's rights activist, Susan B. Anthony, to found the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which advocated a constitutional amendment for women's right to the vote. These two would become the women's movement's most outspoken advocates. Describing their partnership, Cady Stanton would say, "I forged the thunderbolts and she fired them."

D. Extension of slavery and Abolitionism

Slavery, which had up to now received little public attention, began to assume much greater importance as a national issue. In the early years of the republic, when the Northern states were providing for immediate or gradual emancipation of the slaves, many leaders had supposed that slavery would die out. In 1786 George Washington wrote that he devoutly wished some plan might be adopted "by which slavery may be abolished by slow, sure and imperceptible degrees." Jefferson, Madison and Monroe, all Virginians, and other leading Southern statesmen, made similar statements. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had banned slavery in the Northwest Territory. As late as 1808, when the international slave trade was abolished, there were many Southerners who thought that slavery would soon end. The expectation proved false, for during the next generation, the South became solidly united behind the institution of slavery as new economic factors made slavery far more profitable than it had been before 1790.

Slavery, which had up to now received little public attention, began to assume much greater importance as a national issue. In the early years of the republic, when the Northern states were providing for immediate or gradual emancipation of the slaves, many leaders had supposed that slavery would die out. In 1786 George Washington wrote that he devoutly wished some plan might be adopted "by which slavery may be abolished by slow, sure and imperceptible degrees." Jefferson, Madison and Monroe, all Virginians, and other leading Southern statesmen, made similar statements. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had banned slavery in the Northwest Territory. As late as 1808, when the international slave trade was abolished, there were many Southerners who thought that slavery would soon end. The expectation proved false, for during the next generation, the South became solidly united behind the institution of slavery as new economic factors made slavery far more profitable than it had been before 1790.

Chief among these was the rise of a great cotton-growing industry in the South, stimulated by the introduction of new types of cotton and by Eli Whitney's invention in 1793 of the cotton gin, which separated the seeds from cotton. At the same time, the Industrial Revolution, which made textile manufacturing a large-scale operation, vastly increased the demand for raw cotton. And the opening of new lands in the West after 1812 greatly extended the area available for cotton cultivation. Cotton culture moved rapidly from the Tidewater states on the East coast through much of the lower South to the delta region of the Mississippi and eventually to Texas.

Sugarcane, another labor-intensive crop, also contributed to slavery's extension in the South. The rich, hot lands of southeastern Louisiana proved ideal for growing sugarcane profitably. By 1830 the state was supplying the nation with about half its sugar supply. Finally, tobacco growers moved westward, taking slavery with them.

As the free society of the North and the slave society of the South spread westward, it seemed politically expedient to maintain a rough equality among the new states carved out of western territories. In 1818, when Illinois was admitted to the Union, 10 states permitted slavery and 11 states prohibited it; but balance was restored after Alabama was admitted as a slave state. Population was growing faster in the North, which permitted Northern states to have a clear majority in the House of Representatives. However, equality between the North and the South was maintained in the Senate.

In 1819 Missouri, which had 10,000 slaves, applied to enter the Union. Northerners rallied to oppose Missouri's entry except as a free state, and a storm of protest swept the country. For a time Congress was deadlocked, but Henry Clay arranged the so-called Missouri Compromise: Missouri was admitted as a slave state at the same time Maine came in as a free state. In addition, Congress banned slavery from the territory acquired by the Louisiana Purchase north of Missouri's southern boundary. At the time, this provision appeared to be a victory for the Southern states because it was thought unlikely that this "Great American Desert" would ever be settled. The controversy was temporarily resolved, but Thomas Jefferson wrote to a friend that "this momentous question like a firebell in the night awakened me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union."

after 1840 the growing abolitionist movement redefined itself as a crusade against the sin of slave ownership. It mobilized support (especially among religious women in the Northeast affected by the Second Great Awakening).

|

| Frederick Douglass as a younger man |

4. Westward expansion and Manifest Destiny

The American

colonies and the new nation grew very rapidly in population and area, as

pioneers pushed the frontier of settlement west. The process finally ended

around 1890–1912 as the last major farmlands and ranch lands were settled.

Native American tribes in some places resisted militarily, but they were

overwhelmed by settlers and the army and after 1830 were relocated to

reservations in the west. The highly influential "Frontier Thesis" argues

that the frontier shaped the national character, with its boldness, violence,

innovation, individualism, and

democracy.

Recent

historians have emphasized the multicultural nature of the frontier. Enormous

popular attention in the media focuses on the "Wild West" of the

second half of the 19th century. As defined by Hine and Faragher,

"frontier history tells the story of the creation and defense of

communities, the use of the land, the development of markets, and the formation

of states". They explain, "It is a tale of conquest, but also one of

survival, persistence, and the merging of peoples and cultures that gave birth

and continuing life to America."

The frontier

did much to shape American life. Conditions along the entire Atlantic seaboard

stimulated migration to the newer regions. From New England, where the soil was

incapable of producing high yields of grain, came a steady stream of men and

women who left their coastal farmsand villages to take advantage of the rich

interior land of the continent. In the backcountry settlements of the Carolinas

and Virginia, people handicapped by the lack of roads and canals giving access

to coastal markets, and suffering from the political dominance of the Tidewater

planters, also moved westward. By 1800 the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys

were becoming a great frontier region. "Hi-o, away we go, floating down

the river on the O-hi-o," became the song of thousands of migrants.

The westward flow of population in the early 19th century led to the division of old territories and the drawing of new boundaries. As new states were admitted, the political map stabilized east of the Mississippi River. From 1816 to 1821, six states were created -- Indiana, Illinois and Maine (which were free states), and Mississippi, Alabama and Missouri (slave states). The first frontier had been tied closely to Europe, the second to the coastal settlements, but the Mississippi Valley was independent and its people looked west rather than east.

Frontier settlers were a varied group. One English traveler described them as "a daring, hardy race of men, who live in miserable cabins.... They are unpolished but hospitable, kind to strangers, honest and trustworthy. They raise a little Indian corn, pumpkins, hogs and sometimes have a cow or two.... But the rifle is their principal means of support." Dexterous with the axe, snare and fishing line, these men blazed the trails, built the first log cabins and confronted Native American tribes, whose land they occupied.

As more and more settlers penetrated the wilderness, many became farmers as well as hunters. A comfortable log house with glass windows, a chimney and partitioned rooms replaced the cabin; the well replaced the spring. Industrious settlers would rapidly clear their land of timber, burning the wood for potash and letting the stumps decay. They grew their own grain, vegetables and fruit; ranged the woods for deer, wild turkeys and honey; fished the nearby streams; looked after cattle and hogs. Land speculators bought large tracts of the cheap land and, if land values rose, sold their holdings and moved still farther west, making way for others.

Doctors, lawyers, storekeepers, editors, preachers, mechanics and politicians soon followed the farmers. The farmers were the sturdy base, however. Where they settled, they intended to stay and hoped their children would remain after them. They built large barns and brick or frame houses. They brought improved livestock, plowed the land skillfully and sowed productive seed. Some erected flour mills, sawmills and distilleries. They laid out good highways, built churches and schools. Incredible transformations were accomplished in a few years. In 1830, for example, Chicago, Illinois, was merely an unpromising trading village with a fort; but long before some of its original settlers had died, it had become one of the largest and richest cities in the nation.

The westward flow of population in the early 19th century led to the division of old territories and the drawing of new boundaries. As new states were admitted, the political map stabilized east of the Mississippi River. From 1816 to 1821, six states were created -- Indiana, Illinois and Maine (which were free states), and Mississippi, Alabama and Missouri (slave states). The first frontier had been tied closely to Europe, the second to the coastal settlements, but the Mississippi Valley was independent and its people looked west rather than east.

Frontier settlers were a varied group. One English traveler described them as "a daring, hardy race of men, who live in miserable cabins.... They are unpolished but hospitable, kind to strangers, honest and trustworthy. They raise a little Indian corn, pumpkins, hogs and sometimes have a cow or two.... But the rifle is their principal means of support." Dexterous with the axe, snare and fishing line, these men blazed the trails, built the first log cabins and confronted Native American tribes, whose land they occupied.

As more and more settlers penetrated the wilderness, many became farmers as well as hunters. A comfortable log house with glass windows, a chimney and partitioned rooms replaced the cabin; the well replaced the spring. Industrious settlers would rapidly clear their land of timber, burning the wood for potash and letting the stumps decay. They grew their own grain, vegetables and fruit; ranged the woods for deer, wild turkeys and honey; fished the nearby streams; looked after cattle and hogs. Land speculators bought large tracts of the cheap land and, if land values rose, sold their holdings and moved still farther west, making way for others.

Doctors, lawyers, storekeepers, editors, preachers, mechanics and politicians soon followed the farmers. The farmers were the sturdy base, however. Where they settled, they intended to stay and hoped their children would remain after them. They built large barns and brick or frame houses. They brought improved livestock, plowed the land skillfully and sowed productive seed. Some erected flour mills, sawmills and distilleries. They laid out good highways, built churches and schools. Incredible transformations were accomplished in a few years. In 1830, for example, Chicago, Illinois, was merely an unpromising trading village with a fort; but long before some of its original settlers had died, it had become one of the largest and richest cities in the nation.

Farms were

easy to acquire. Government land after 1820 could be bought for $1.25 for about

half a hectare, and after the 1862 Homestead Act, could be claimed by merely

occupying and improving it. In addition, tools for working the land were easily

available. It was a time when, in a phrase written by John Soule and

popularized by journalist Horace Greeley, young men could "go west and

grow with the country."

Except for a

migration into Mexican-owned Texas, the westward march of the agricultural

frontier did not pass Missouri until after 1840. In 1819, in return for

assuming the claims of American citizens to the amount of $5 million, the

United States obtained from Spain both Florida and Spain's rights to the Oregon

country in the Far West. In the meantime, the Far West had become a field of

great activity in the fur trade, which was to have significance far beyond the

value of the skins. As in the first days of French exploration in the

Mississippi Valley, the trader was a pathfinder for the settlers beyond the

Mississippi. The French and Scots-Irish trappers, exploring the great rivers

and their tributaries and discovering all the passes of the Rocky and Sierra

Mountains, made possible the overland migration of the 1840s and the later

occupation of the interior of the nation.

Overall, the

growth of the nation was enormous: population grew from 7.25 million to more

than 23 million from 1812 to 1852, and the land available for settlement

increased by almost the size of Europe - from 4.4 million to 7.8 million

square kilometers. Still unresolved, however, were the basic conflicts rooted

in sectional differences which, by the decade of the 1860s, would explode into

civil war. Inevitably, too, this westward expansion brought settlers into

conflict with the original inhabitants of the land: the Indians.

In the first

part of the 19th century, the most prominent figure associated with these

conflicts was Andrew Jackson, the first "Westerner" to occupy the

White House. In the midst of the War of 1812, Jackson, then in charge of the

Tennessee militia, was sent into southern Alabama, where he ruthlessly put down

an uprising of Creek Indians. The Creeks soon ceded two-thirds of their land to

the United States. Jackson later routed bands of Seminole Indians from their

sanctuaries in Spanish-owned Florida.

In the 1820s,

President Monroe's secretary of war, John C. Calhoun, pursued a policy of

removing the remaining tribes from the old Southwest and resettling them beyond

the Mississippi. Jackson continued this policy as president.

In 1830

Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, providing funds to transport the

eastern tribes beyond the Mississippi. In 1834 a special Indian territory was

set up in what is now Oklahoma. In all, the tribes signed 94 treaties during

Jackson's two terms, ceding millions of hectares to the federal government and

removing dozens of tribes from their ancestral homelands.

Perhaps the most egregious chapter in this unfortunate history concerned the Cherokees, whose lands in western North Carolina and Georgia had been guaranteed by treaty since 1791. Among the most progressive of the eastern tribes, the Cherokees' fate was sealed when gold was discovered on their land in 1829. Even a favorable ruling from the Supreme Court proved little help. With the acquiescence of the Jackson administration, the Cherokees were forced to make the long and cruel trek to Oklahoma in 1835. Many died of disease and privation in what became known as the "Trail of Tears."

Perhaps the most egregious chapter in this unfortunate history concerned the Cherokees, whose lands in western North Carolina and Georgia had been guaranteed by treaty since 1791. Among the most progressive of the eastern tribes, the Cherokees' fate was sealed when gold was discovered on their land in 1829. Even a favorable ruling from the Supreme Court proved little help. With the acquiescence of the Jackson administration, the Cherokees were forced to make the long and cruel trek to Oklahoma in 1835. Many died of disease and privation in what became known as the "Trail of Tears."

Through wars

and treaties, establishment of law and order, building farms, ranches, and

towns, marking trails and digging mines, and pulling in great migrations of

foreigners, the United States expanded from coast to coast fulfilling the

dreams of Manifest Destiny. As the

American frontier passed into history, the myths of the west in fiction and

film took firm hold in the imagination of Americans and foreigners alike.

America is exceptional in choosing its iconic self-image. "No other

nation," says David Murdoch, "has taken a time and place from its

past and produced a construct of the imagination equal to America's creation of

the West."

From the early

1830s to 1869, the Oregon

Trail and its many offshoots were used by over 300,000 settlers. '49ers (in

the California Gold Rush), ranchers, farmers, and

entrepreneurs and their families headed to California, Oregon, and other points

in the far west. Wagon-trains took five or six months on foot; after 1869, the

trip took 6 days by rail.

Manifest

Destiny was the belief that American settlers were destined to expand across

the continent. This concept was born out of "A sense of mission to redeem

the Old World by high example ... generated by the potentialities of a new

earth for building a new heaven." Manifest Destiny was rejected by

modernizers, especially the Whigs like Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln who

wanted to build cities and factories – not more farms. Democrats strongly favored expansion, and they won the key

election of 1844. After a bitter debate in Congress the Republic of Texas was annexed in 1845,

which Mexico had warned meant war.

|

| The American occupation of Mexico City during the Mexican–American War. |

War broke out

in 1846, with the homefront polarized as Whigs opposed and Democrats supported

the war. The U.S. army, using

regulars and large numbers of volunteers, won the Mexican–American

War (1846–48). The 1848 Treaty

of Guadalupe Hidalgo made peace. Mexico recognized the annexation of

Texas and ceded its claims in the Southwest (especially California and New

Mexico).

The Hispanic

residents were given full citizenship and the Mexican

Indians became American

Indians. Simultaneously gold was discovered, pulling over 100,000 men to northern

California in a matter of months in the California

Gold Rush. Not only did the then president James

K. Polk expand America's border to the Republic of Texas and

a fraction

of Mexico but he also annexed the north western frontier known as the Oregon Country, which was renamed the Oregon Territory.

5. Divisions between North and South

|

Union states: navy blue (free) and yellow (slave [also known as Border states)

Confederacy states: brown (slave) U.S. territories: lighter shades of blue and brown

|

Religious

activists split on slavery, with the Methodists and Baptists dividing into

northern and southern denominations. In the North, the Methodists,

Congregationalists, and Quakers included many abolitionists, especially among

women activists. (The Catholic, Episcopal and Lutheran denominations largely

ignored the slavery issue.)

The issue of

slavery in the new territories was seemingly settled by the Compromise of 1850, brokered by

Whig Henry Clay and Democrat Stephen Douglas; the

Compromise included the admission of California as a free

state. The point of contention was the Fugitive Slave Act, which

increased federal enforcement and required even free states to cooperate in

turning over fugitive slaves to their owners. Abolitionists pounced on the Act

to attack slavery, as in the best-selling anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet

Beecher Stowe.

The Compromise of 1820 was

repealed in 1854 with the Kansas–Nebraska

Act, promoted by Senator Douglas in the name of "popular

sovereignty" and democracy. It permitted voters to decide on slavery in each

territory, and allowed Douglas to say he was neutral on the slavery issue.

Anti-slavery forces rose in anger and alarm, forming the new Republican Party. Pro- and anti- contingents rushed to Kansas to vote

slavery up or down, resulting in a miniature civil war called Bleeding Kansas. By the late

1850s, the young Republican Party dominated nearly all northern states and thus

the electoral college. It insisted that slavery would never be allowed to

expand (and thus would slowly die out). The Southern slavery-based societies

had become wealthy based on their cotton and other agricultural commodity production,

and some particularly profited from the internal slave trade. Northern cities

such as Boston and New York, and regional industries, were tied economically to

slavery by banking, shipping, and manufacturing, including textile mills. By 1860,

there were four million slaves in the

South, nearly eight times as many as there were nationwide in 1790. The plantations were

highly profitable, because of the heavy European demand for raw cotton. Most of

the profits were invested in new lands and in purchasing more slaves (largely

drawn from the declining tobacco regions).

For 50 of the

nation's first 72 years, a slaveholder served as President of the United States

and, during that period, only slaveholding presidents were re-elected to second

terms. In addition, southern states benefited by their increased

apportionment in Congress due to the partial counting of slaves in their populations.

Slave

rebellions were planned or actually took place – including by Gabriel Prosser (1800), Denmark Vesey (1822), Nat Turner (1831),

and John

Brown (1859) – but they only involved dozens of people and all failed.

They caused fear in the white South, which imposed tighter slave oversight and

reduced the rights of free

blacks. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 required the states to cooperate with

slave owners when attempting to recover escaped slaves, which outraged

Northerners. Formerly, an escaped slave, having reached a non-slave state, was

presumed to have attained sanctuary and freedom. The Supreme Court's 1857

decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford ruled

that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional; angry Republicans said this

decision threatened to make slavery a national institution.

After Abraham Lincoln won

the 1860 election, seven

Southern states seceded from the

union and set up a new nation, the Confederate

States of America (C.S.A.), on February 8, 1861. It attacked Fort Sumter, a U.S. Army

fort in South Carolina, thus igniting the war. When Lincoln called for troops

to suppress the Confederacy in April 1861, four more states seceded and joined

the Confederacy. A few of the (northernmost) "slave

states" did not secede and became known as the border

states; these were Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri.

During the war, the northwestern portion of Virginia seceded from the C.S.A. and became the new Union state of West Virginia. West Virginia is usually grouped with the border states.

During the war, the northwestern portion of Virginia seceded from the C.S.A. and became the new Union state of West Virginia. West Virginia is usually grouped with the border states.

SIDEBAR: SENECA FALLS

The early

feminist, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, found an ally in Lucretia Mott, an ardent

abolitionist, when the two met in 1840 at an anti-slavery conference in London.

Once the conference began, it was apparent to the two women that female

delegates were not welcome. Barred from speaking and appearing on the

convention floor, Cady Stanton and Mott protested by leaving the convention

hall, taking other female delegates with them. It was then that Cady Stanton

proposed to Mott a women's rights convention that would address the social,

civil and religious rights of women. The convention would be put on hold until

eight years later, when the two organized the first women's rights convention,

held in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848.

At that

meeting, Cady Stanton presented a "Declaration of Sentiments," based

on the Declaration of Independence, and listing 18 grievances against male

suppression of women. Among them: married women had no right to their children

if they left an abusive husband or sought a divorce. If a woman was granted a

divorce, there was no way for her to make a professional living unless she

chose to write or teach. A woman could not testify against her husband in

court. Married women who worked in factories were not entitled to keep their

earnings, but had to turn them over to their husbands. When a woman married,

any property that she had held as a single woman automatically became part of

her husband's estate. Single women who owned property were taxed without the

right to vote for the lawmakers imposing the taxes -- one of the very reasons

why the American colonies had broken away from Great Britain.

Convention

attendees passed the resolutions unanimously with the exception of the one for

women's suffrage. Only after an impassioned speech in favor of women's right to

vote by Frederick Douglass, the black abolitionist, did the resolution pass.

Still, the majority of those in attendance could not accept the thought of

women voting.

At Seneca Falls, Cady Stanton gained national prominence as an eloquent writer and speaker for women's rights. Years later, she declared that she had realized early on that without the right to vote, women would never achieve their goal of becoming equal with men. Taking the abolitionist reformer William Lloyd Garrison as her model, she saw that the key to success in any endeavor lay in changing public opinion, and not in party action. By awakening women to the injustices under which they labored, Seneca Falls became the catalyst for future change. Soon other women's rights conventions were held, and other women would come to the forefront of the movement for political and social equality.

At Seneca Falls, Cady Stanton gained national prominence as an eloquent writer and speaker for women's rights. Years later, she declared that she had realized early on that without the right to vote, women would never achieve their goal of becoming equal with men. Taking the abolitionist reformer William Lloyd Garrison as her model, she saw that the key to success in any endeavor lay in changing public opinion, and not in party action. By awakening women to the injustices under which they labored, Seneca Falls became the catalyst for future change. Soon other women's rights conventions were held, and other women would come to the forefront of the movement for political and social equality.

No comments:

Post a Comment